Eighty-eight years ago thousands of U.S. military veterans gathered their belongings and began a long march across the country to Washington, D.C. Once there, they pitched their canvas tents in neatly ordered rows and dug in for a long fight.

By the summer of 1932, what began as a small movement in Portland, Oregon had burgeoned into a national demonstration, bringing together a socially, economically and racially diverse coalition under a single banner, with each participant bound by a shared experience: When their country called them to arms, they answered.

(Editor’s note: This article was originally published on July 28, 2020.)

Numbering as many as 25,000-strong, with families and children in tow, they called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, but colloquially, became known as the Bonus Army. These World War I veterans, like many demonstrators before and since, gathered to demand that the government keep its word. In their case, it was the early payment of a bonus they had been promised following victory in the First World War.

Through the Adjusted Compensation Act of 1924, the funds were set to be doled out in 1945. Originally the bonuses were to be paid immediately, but for budgetary reasons, they were delayed by two decades. Five years after the bill was passed, the Great Depression hit, and by 1932, the financial crisis had reached its peak. Amidst the economic fallout, the promise of deferred payments amounted to a shriveled carrot dangling from the end of a very long stick.

On July 19 of that year, retired Marine Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler took to the stage at the largest Bonus Army camp, located at the Anacostia Flats, a swampy stretch of ground outside of downtown D.C. There he launched into a fiery tirade that remains relevant to military veterans, and Americans at large, even to this day.

The first time I watched the scratchy black and white footage, which was recorded by a local news crew, I couldn’t take my eyes off Butler. Up there in front of that crowd, with his trousers hiked high up on his waist, with his suspenders and tie, and his sleeves — one rolled, the other rebellious cuff slipping down on his arm from all the animated fist-pumping and gesticulating. He was like a righteously furious Marine Corps Mr. Rogers.

But then I listened to what he was saying.

“I never saw such fine Americanism as is exhibited by you people,” Butler says in the roughly 10-minute-long newsreel, a copy of which was provided to Task & Purpose by the University of South Carolina.

“You have just as much right to have a lobby here as any steel corporation,” Butler continued. “Makes me so damn mad, a whole lot of people speak of you as tramps. By God, they didn’t speak of you as tramps in 1917 and ’18.”

For many, especially Marines, Butler is a name learned at boot camp — memorized by recruits because he earned the nation’s highest award for valor twice. He was a far more complex and controversial figure: A distinguished Marine, beloved by his men, but viewed as a hot-tempered loose cannon by some of his superiors, Butler left the Corps after 33 years of service and became an outspoken critic of the military-industrial complex, even coining the anti-imperialist slogan with his book War is a Racket.

The Smedley Butler on stage in that old black and white clip is that Smedley Butler.

“I mean just what I say. I don’t want anything. Nobody can kick me anymore, and I’ll say what I please,” Butler quips in the speech, like the two-star general equivalent of holding up your discharge papers and saying what are you gonna do, send me back to the front?

The video, which belongs to the Fox Movietone News Collection at the University of South Carolina, was shot by C.J. Davis, a cameraman for Fox Movietone News, as part of a newsreel that would have been shown in theaters — usually before a feature film — which suggests that the Bonus Army’s struggle, and Butler’s address, likely reached a wide audience. (Note: The full video can be found at the bottom of this article.)

“Take it from me, this is the greatest demonstration of Americanism we have ever had. Pure Americanism,” Butler adds in the segment. “Don’t make any mistake about it: You’ve got the sympathy of the American people. Now, don’t you lose it!”

A two-time Medal of Honor recipient, one of only four, the other three being Marines, as Butler liked to point out, he was there to boost morale and encourage demonstrators to stand their ground, and it’s no surprise why; Butler knew how to give a speech.

“He was a very upbeat, kind of grizzled, tell it like it is kind of guy when he was in the Marine Corps, which made him very popular with the enlisted Marines,” Ed Nevgloski, the director of the Marine Corps History Division, told Task & Purpose. “When he believes in something, he goes all out, and he doesn’t take no for an answer.”

Butler’s arrival at the veterans’ camp came at an inflection point in the movement and in American politics. It was a time when the country was literally divided along racial lines due to segregation imposed by Jim Crow laws, and the rift between the haves and have nots had grown dramatically during the Great Depression. The words “fascist” and “communist” weren’t used solely as insults in partisan debates, or flung across Twitter to silence an argument, but referred to established political camps who were vying for greater influence in the United States. And on top of all that, within a decade, the U.S. would be embroiled in yet another World War.

To say it was a complicated moment in American history would be a profound understatement.

Despite the political tension, massive demonstrations, social injustice, and sweeping poverty, the Bonus Expeditionary Force and their military-style camps were small dots of unity in a divided nation.

As Lauren Katzenberg with The New York Times pointed out, in June 1932, Roy Wilkins, a reporter for the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis, visited the marchers in Washington writing that:

“Black men and white men, veterans of the segregated Army that had fought in World War I, lined up equally, perspired in sick bays side by side. For years the U.S. Army had argued that General Jim Crow was its proper commander, but the Bonus marchers gave lie to the notion that black and white soldiers — ex-soldiers in their case — couldn’t live together.”

At a time when Americans were divided based on the color of their skin, and even the military itself was racially segregated, the veteran camps were not.

“That’s what I really like about videos like that, films like that, where you can actually see the fabric of America and the unity of America,” Nevgloski told Task & Purpose. “I think it’s emblematic of who we are as American military veterans.”

“Most every military veteran organization in this country, you’ll see people from all walks of life together because they had one thing in common: That they wore the uniform and they wanted to commiserate with people that were just like them,” Nevgloski continued. “They want to be around people that were just like them, who made the same sacrifices, had the same values, and it doesn’t matter what your skin color is.”

Around the time that Butler addressed the Bonus Army marchers, the government had taken to offering travel vouchers to members to convince them to return home, explained Greg Wilsbacher, the curator for the University of South Carolina’s Newsfilm and Military Collections.

It was a tempting lure to the mass of men, and their families, who had spent weeks living in military-style camps in the nation’s capital, and who were, quite frankly, only there out of sheer financial desperation.

“It was one last attempt to rally public sympathy to keep everybody together,” Wilsbacher said of Butler’s address.

And the situation was dire for the Bonus Army. After the House passed legislation to see the veterans’ payments expedited, the bill was struck down by the Senate, and then-President Herbert Hoover had sworn to veto the bill if it made it through Congress.

On July 28, little more than a week after Butler’s speech, the Bonus Expeditionary Force was forcibly removed from their camps — one on Constitution and another on Pennsylvania Ave., and the largest, located across the river in Anacostia.

After a confrontation between the veteran demonstrators and city police led to violence, scores were injured and two veterans were shot and killed: Eric Carlson and William Hushka.

As The Washington Post reported in 2017, Carlson, who’d fought in the trenches on the Western Front, died of his wounds five days after the riot, and Hushka, a Lithuanian immigrant who took his oath of citizenship during boot camp, died instantly.

In a turn of tragic irony, Carlson and Hushka were the only two Bonus Army members to receive the money they were due while the movement was in full swing, though it came at the highest of costs. After their deaths, the federal government paid out their bonuses to each of the veteran’s families.

“It’s almost as if ‘is that what it took?’ Was that their best option to support their families at that point in time, was to die early and have their bonuses paid out?” said Wilsbacher, before adding “which is pretty grim.”

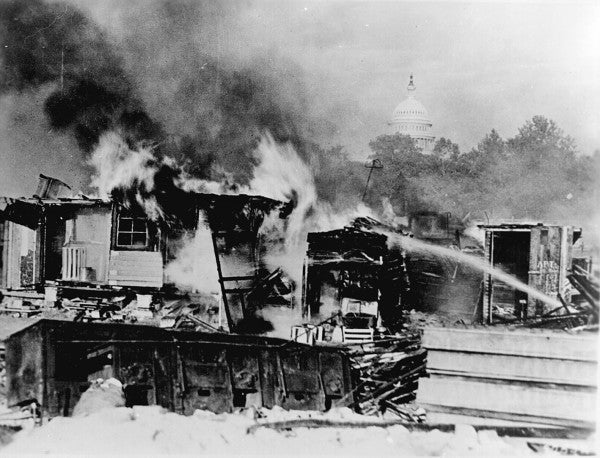

As the police and the veterans struggled, U.S. Army troops moved in. Leading tanks, cavalry, and armed soldiers with bayonets fixed down Pennsylvania Avenue, soon-to-become famous military figures Douglas MacArthur, George Patton, and future president Dwight Eisenhower rousted the Bonus Marchers with tear gas, and torched the veterans’ camps in downtown Washington, before pursuing the marchers over the bridge to their Anacostia encampment.

Photos and footage of the veterans’ camp in flames shocked the country. The news that police and the U.S. military had used force against a gathering of largely peaceful demonstrators who had just won the country’s most recent war — and who were protesting for the right to receive what had already been promised to them by the government — was, to put it bluntly, a disaster for the Hoover administration.

During the 1932 presidential election, Hoover lost to Franklin D. Roosevelt, badly. In the years that followed, the remaining Bonus Marchers and the Roosevelt administration came to an agreement. And though it didn’t happen overnight, by 1936 the World War I veterans received their long-awaited, and hard-fought-for bonus.

In the ensuing years, the march of the Bonus Army spurred sweeping changes in how the federal government supported and cared for its service members once the fighting had ended, and in July 1944, Roosevelt signed the G.I. Bill of Rights into law, providing education and housing benefits as an immediate reward for honorable military service.

Had it not been for the thousands who endured the sweltering summer heat of Washington, who faced down police barricades and batons, and stood shoulder-to-shoulder as tear gas was hurled by armed troops, it’s unlikely any of that would have come to pass.

“It’s not the first time that the U.S. government, as you know, has taken back or rescinded a promise that they made, and to give up so easily, just wouldn’t have been the right thing to do,” Nevgloski told Task & Purpose.

“That’s where someone like Smedley Butler comes in and is telling these guys, ‘you fight long and hard for what you’ve earned, and whether it’s these bonuses or it’s something else, you know, you have the magic key, and it’s called the ability to vote and use that vote wisely. And if Congress doesn’t want to listen to you and doesn’t want to provide you with that bonus, well, you vote them out of office.’”

And Butler’s words that day, all those years ago, still bear true:

“When you exercise your right as a citizen, which is voting, remember that everybody who’s not with you is against you, there’s no such thing as a middle course,” Butler said during his speech. “If anybody’s with you, he’ll say so. And if he doesn’t say anything, he’s against you, and when you go to the polls, lick the hell out of him!”

“Doesn’t make any difference what he is. This is not a business of party, this is a business of the people. This isn’t a question of whether it’s right for you to have the bonus or not — things don’t go that way. It doesn’t go by justice, it goes by votes! And if you want your bonus, you’ll get the votes, and you can have 10 times the bonus if you get the votes.”

You can watch Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler’s July 19, 1932 speech to the Bonus Army in its entirety below:

The post Smedley Butler’s fiery speech to World War I veterans is still relevant today appeared first on Task & Purpose.