The Air Force shared a Facebook post for Pride Month on Tuesday honoring Tech Sgt. Leonard Matlovich, a Vietnam War veteran with a distinguished service record who the Air Force kicked out in 1975 after he came out as gay to his commanding officer.

The Facebook post makes no mention of the service ousting Matlovich, and instead focuses just on the airman’s role as being one of the first service members to publicly out himself for the sake of advancing the gay rights movement.

“Since Matlovich’s challenge in 1975, the military has come a long way in taking steps toward inclusivity,” the Air Force wrote in its post, referring to the 2011 repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, the policy which forbade gay or lesbian men and women from serving publicly in the military.

“The all-volunteer force thrives when it is composed of diverse Americans who can meet the rigorous standards for military service, and an inclusive military strengthens our national security,” the Air Force continued, marking a shift in tone since Matlovich’s days in the service.

Born to a Catholic Air Force family in Savannah, Georgia, Matlovich grew up racist and homophobic, a “white racist … flag-waving patriot,” by his own admission. He followed his father’s footsteps into the Air Force in 1963 at the age of 19 and served three tours in Vietnam, where he earned a Bronze Star for killing two Viet Cong soldiers attacking his post while he was on sentry duty, according to the Washington Post. He later earned a Purple Heart for being wounded after stepping on a Viet Cong land mine.

“I had to prove that I was just as masculine as the next man. I felt Vietnam would do this for me,” he said, according to the 2007 book Ask and Tell: Gay and Lesbian Veterans Speak Out.

Despite being outwardly homophobic, Matlovich always knew he was gay, according to the New York Times. Over time, his bias against homosexuals began to fade, along with his bias against African-Americans, who he found himself serving alongside and taking orders from during his time in the Air Force.

“One stereotype after another stereotype started to crumble,” he told The New York Times.

Though it was unclear what Matlovich’s job in the Air Force was while in Vietnam, while based in Fort Walton Beach, Florida, he became a race relations instructor to help ease racial tensions in the Air Force. He started going to gay bars in Pensacola, slept with a man for the first time, came out to several of his friends, and learned more about the still-nascent gay rights movement.

A turning point came in 1974, when Matlovich read an article in Air Force Times about the gay rights activist Frank Kameny (who was honored in a Google Doodle earlier this week). Kameny was looking for a test case to challenge the military’s ban on gays, and Matlovich stepped up to take it on. It would likely mean sacrificing his military career, but it was a risk the airman was willing to take.

“He … was the epitome of a perfect soldier, one of those people that stuck his neck out, and he was proud to be the person to challenge that law,” Jeff Dupre, a longtime friend of Matlovich, told NPR in 2015.

In March, 1975, the airman hand-delivered a coming-out letter to his commanding officer at Langley Air Force Base, Virginia.

“In sum, I consider myself to be a homosexual and fully qualified for further military service,” Matlovich wrote at the end of his letter. “My almost twelve years of unblemished service supports this position.”

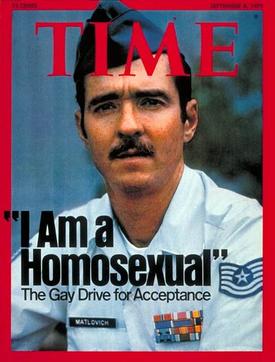

The Air Force in 1975 did not share the airman’s position, despite the tone of its Facebook post on Tuesday. The service gave Matlovich a general (not honorable) discharge in October 1975, and when the airman said he wanted the decision to be reviewed, the review board refused to do so, according to Time magazine. But the month prior, Matlovich made history by being the subject of a cover story for Time magazine.

“I am a homosexual” read the title in bold under the airman’s uniformed portrait, marking a massive step in the gay rights movement.

“It marked the first time the young gay movement had made the cover of a major newsweekly,” said renowned author Randy Shilts in his 1993 book Conduct Unbecoming, about discrimination against lesbians and gays in the military. “To a movement still struggling for legitimacy, the event was a major turning point.”

“Even the most hardened homophobe had to take pause when he reviewed Matlovich’s record,” Shilts wrote. “Credentials such as a Bronze Star, a Purple Heart, and twelve years of outstanding service meant something that civilians could barely imagine. As one wizened sergeant told Matlovich at Langley one day, ‘You can’t have a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star and suck cock.’”

The Air Force eventually settled a lawsuit protesting Matlovich’s discharge in 1980, but, the former airman continued to advocate for gay rights years after he left the military. Like thousands of other gay men around the world, Matlovich contracted HIV in the 1980s, though that didn’t stop him from being arrested in front of the White House in June, 1987 for protesting against President Ronald Reagan’s negligent response to the crisis.

Matlovich died shortly before his 45th birthday in 1988. His tombstone in Washington, D.C., does not bear his name, and instead reads “A Gay Vietnam Veteran,” below which is the line “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.”

It’s not wrong for the Air Force to celebrate Matlovich’s legacy on its Facebook page, but the service is whitewashing history when it does not acknowledge or take responsibility for ousting the airman from its ranks. Even more unfortunate are some of the comments written in response to the post, some of which sound like nothing has changed since the 1970s.

“I am a veteran of the Air Force and am disgusted by the way it went from the greatest in the world, to a political [sic] correct military,” wrote one Facebook user.

“Maybe I am old school, but I would not have served under someone like him,” wrote another.

Tech. Sgt. Matlovich may not have been surprised. According to Time, he said this to reporters who swarmed his discharge hearing in 1975.

“Maybe not in my lifetime, but we are going to win in the end.”

He’s not alone though. Between the hateful comments were more positive ones.

“As a trans veteran, I appreciate seeing posts like this,” wrote one commenter. “Hoping for a better future for those currently serving and those who will serve!”

Related: How an Army veteran designed the iconic symbol of the gay rights movement