Editor’s note: This article was originally published on June 12, 2017. Former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld died on June. 29, 2021, at the age of 88.

“Boy, that one in the middle was really going after Trump,” Donald Rumsfeld said, adjusting the cuffs of his pinstriped navy blue suit, as he stepped into a sparsely furnished green room at ABC Studios in Manhattan. The former secretary of defense, who at 84 still exudes an air of supreme confidence, had just completed a lengthy — and, at times, awkward — interview on “The View.” Now, addressing one of his assistants, he pointed to a wall-mounted with photographs of the show’s co-hosts and fingered the culprit. “The one in the middle” was Joy Behar, who had pressed Rumsfeld to weigh in on allegations that the Trump administration had colluded with the Russians. If it’s true, one of Behar’s colleagues asked, should the president be impeached?

“Why do you want to engage in hypotheticals?” Rumsfeld responded, eliciting an eye roll from Whoopi Goldberg. Then, after some back and forth, and a few more eye rolls, he added: “I have the sense that you may be jumping to conclusions.”

The retort was met with a light smattering of applause, but the hosts kept at it. “You’re retired now, Donny,” Beher quipped, a little jab at an ego that could withstand a direct hit from a thermonuclear bomb. From there, the conversation devolved into a game of cat and mouse — five cats, one mouse — that ultimately left the hosts empty-handed, deprived of the soundbite that would’ve placed one of the most reviled conservative officials of the 21st century firmly within the anti-Trump camp. See, even Rummy hates this guy! Beher would say. Twitter would explode. But Rumsfeld never copped to any pro-Trump leanings, either. He simply did what Rumsfeld does when he talks to the press: He played his cards close to the vest.

As it happens, playing cards — the real kind — were exactly what Rumsfeld had come to New York on this rainy Thursday in late May to discuss. He was on a small media tour to promote his phone app, called Churchill Solitaire (for iPhone and Android), the proceeds of which would support the Travis Manion Foundation, a veterans nonprofit. “The View” hosts had fumbled through that portion of the interview, at one point even referring to the Travis Manion Foundation by the wrong name. They never asked about the app.

After the taping, Rumsfeld sat down with Task & Purpose to discuss the same subject. “Please tell me you were smart enough to download the game,” Rumsfeld said as we arrived for lunch at Sardi’s, a famous restaurant near the Theater District that is decorated with hundreds of illustrated caricatures of celebrities — patrons, presumably. “Whoopi!” Rumsfeld exclaimed, pointing, for a second time that day at a picture on a wall.

There was also a picture of Tom Cruise, who had just announced that a “Top Gun” sequel is in the works. I asked Rumsfeld if he was a fan of the original. After all, like Lt. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, the film’s hunky hero (played by a 23-year-old Cruise), Rumsfeld had flown aircraft for the Navy. He was commissioned in the late 1950s — following in the footsteps of his father, who had been a naval officer during World War II — and served as a pilot for more than two decades, first on active duty and then in the reserve. But Rumsfeld had never seen “Top Gun.”

“You’d love it,” said Keith Urbahn, his young and bespectacled protege, who currently serves as an intelligence officer in the Navy Reserve. Rumsfeld replied: “Oh, I think I’ll be critical. Does Tom Cruise even know how to fly?” This led to a story about the time Rumsfeld had dinner with actor, director, and occasional spokesman for the Republican Party, Clint Eastwood. Apparently, Eastwood had met with many Pentagon officials, including Rumsfeld, while researching his World War II epic, “Letters from Iwo Jima.”

“He was an appealing guy,” Rumsfeld said. “An awfully nice man. I’m sure Cruise is, too.”

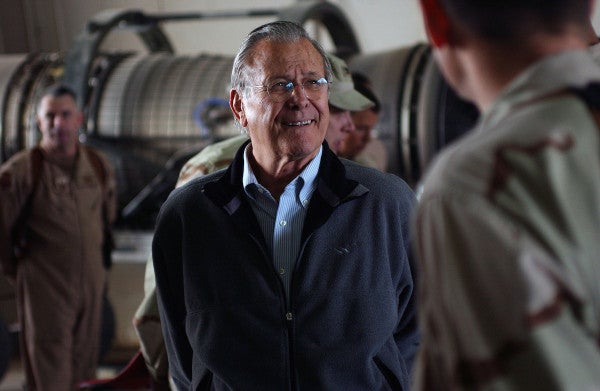

This is Rumsfeld in retirement: reflective, warm, genial, and safely removed from the cutthroat world of politics in which he was once a ruthless player. He seems to enjoy acting the old codger — cheerfully informing me that he just had a knee replacement, that he’s a great-grandfather, and that the official adjective to describe someone his age is octogenarian (“Do you use big words like that when you write?” he asked me, teasingly). All of this information was administered with a tinge of amusement. One primary benefit of being an octogenarian, I gather, is that you get to say things like, “I’m just an old man,” and, “I’m retired,” and, “Oh, I don’t remember,” to avoid answering tough questions, such as how he feels about his role in the Iraq War, which was prosecuted under false pretenses during his tenure as secretary of defense, or the chaos it unleashed in the region. It’s all a ruse. He remembers everything.

Rumsfeld’s political career began in earnest when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives at the age of 30. He was, in many ways, a moderate Republican. He supported the 1964 Civil Rights Act, advocated an end to the draft, and co-sponsored the Freedom of Information Act, which President Lyndon Johnson signed into law in 1966. But he also had a reputation for combativeness, a trait that had helped him excel as a wrestler and football player at Princeton. And, of course, also as a politician: President Richard Nixon famously described Rumsfeld as “a ruthless little bastard.” That was a compliment. In 1975, after serving in various roles in the Nixon administration, and as Ambassador to NATO, Rumsfeld was appointed secretary of defense by President Gerald Ford, becoming the youngest person to ever hold that position. Twenty-six years later, he became the oldest person to ever hold the job when he was again appointed defense secretary, this time by President George W. Bush.

Several months later, the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks happened, catalyzing a paradigm shift in American foreign policy. The attacks had been masterminded in Afghanistan by a Saudi of Yemeni descent, who commanded a network of jihadists that could not be contained by national borders and was loyal to no official government. Suddenly, the world was our battlefield. Or at least that’s how Rumsfeld saw it. He shared Bush’s view that the Global War on Terror would need to be waged over many years and in many countries. Rumsfeld’s insistence that the effort would require, as he said, “a long, hard slog” against an elusive and stateless enemy clashed with Secretary of State Colin Powell’s belief that U.S. military action should always have a clear objective and a concrete exit strategy. In December 2001, Rumsfeld publicly ridiculed Powell after the secretary of state told reporters that al Qaeda had been “destroyed” in Afghanistan, and that the country was no longer a terrorist safe haven. By that point, under orders from Bush, Rumsfeld had already begun drawing up plans for striking Iraq, where al Qaeda had yet to establish a foothold. Though Saddam Hussein’s crimes were legion, being soft on Islamic extremism wasn’t one of them, and we’re still dealing with the after effects of his overthrow.

But the Iraq war overshadowed the strategic shift that is perhaps Rumsfeld’s greatest legacy: his restructuring of the U.S. military into a leaner, more agile and versatile fighting force that would rely more heavily on special forces and unconventional warfare tactics.

“If you’re very capable on conventional capabilities, the chances of someone competing with you in those conventional areas goes down,” he told me when I asked why he had pushed so hard for the creation of the U.S. Marine Special Operations Command, which was stood up in 2006, despite fierce resistance from the Corps. “And that means that the probability of you being competed against on something other than your conventional capabilities goes up. That’s the essence of my logic, and why I spent time doing what I did, pushing the services to be — not change their orientation — but add a stronger element in the area.”

That logic helps account for the fact that the 2003 invasion of Iraq involved the largest deployment of special operations soldiers since Vietnam. It also accounts for the inadequate troop numbers on the ground for the post-invasion phase of the war (“Stuff happens,” Rumsfeld infamously told the press in 2003 as Baghdad unraveled) and, ultimately, Rumsfeld’s ouster in 2006 amid accusations of incompetence from a group of retired generals and admirals, many of whom had commanded troops in Iraq.

The closest Rumsfeld has ever come to publicly second-guessing the invasion of Iraq and the management of the war while he was secretary of defense was when, in 2015, he told the Times of London that he thought Bush’s idea that the United States could transform Iraq into a democracy was “unrealistic.” But several days later, he clarified his remarks in an interview with CNN, saying, “… the goal was to have Saddam Hussein not be there, and to have what replaced Saddam Hussein be a government that would not have weapons of mass destruction, that would not invade its neighbors, and that would be reasonably respectful of diverse ethnic groups.” Otherwise, Rumsfeld has stood firmly by his decisions. He was just doing his job.

He mostly kept quiet in the intervening years, with the notable exception of his appearance in “The Known Unknowns,” an acclaimed documentary portrait of him by Errol Morris. But in 2016, Rumsfeld raised eyebrows by releasing a smartphone app, Churchill Solitaire, an electronic version of a card game that he’s been obsessed with for decades. He learned of it, he said, from a Belgian diplomat who claimed to have been taught the game by Rumsfeld’s personal hero, Winston Churchill. “I was afraid that it’d be lost to the ages,” Rumsfeld said. It’s a frustratingly difficult version of traditional solitaire, which is a point of pride for Rumsfeld, a self-described master. Still, the app has been downloaded more than a million times and raised upward of $500,000 for the foundation. The app, which was being promoted again on the eve of Memorial Day, is free, but you have to pay for “undos” and “hints.” Rumsfeld told me he’s never used either.

Despite the app’s success, he gives full credit to Churchill. “I’m sure I’ve never had an original idea,” he said. “I’ve talked to so many brilliant people all the time, that something sparks, and I end up liking the idea, and we pushed it.”

Some of those ideas were extremely controversial, I noted.

“There’s nothing wrong with a little resistance,” he replied. “There’s always resistance. That’s okay. That forces you to think through what you’re doing and make sure you’ve thought it through pretty well before you do it.”

This is the point in the story where I’m obligated to point out that there are no “undos” when it comes to waging war — as many journalists slyly pointed out when they covered the debut of the app last year. How could they not? By most mainstream accounts, Rumsfeld helped make the bed that the rest of us have been sleeping in since he slipped off into a comfortable retirement. Many foreign policy experts draw a direct link from the invasion of Iraq and the droves of jihadists that it drew into the region to the Syrian civil war and the subsequent rise of ISIS. Even Trump, a Republican, ran on a platform that heavily criticized the Iraq War as a tragic waste of human lives and resources. But Rumsfeld, a staunch party loyalist, has yet to issue an opinion on the president — “I’ve never met the guy,” he said.

He did, however, offer up a favorable assessment of Defense Secretary James Mattis, also a critic of the Iraq War and a folk hero among the troops. “I think he’s an excellent choice,” he said. “I think Trump’s national security team is first rate. I don’t know Tillerson, but Mattis is very, very good. He’s respected, he’s measured, he’s thoughtful. He reads, he thinks, and I think he’ll be a very good advisor to the president.”

Joining us at lunch was Ryan Manion, the sister of Travis Manion and spokeswoman for the foundation named in his honor.

Travis had been an all-American guy, the son of a Marine. Like Rumsfeld, he wrestled in college, at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. He was tough and charismatic, with a square jaw that looked custom-built for a kevlar helmet. After college, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Marines. In April 2007, during his second tour to Iraq, the patrol Travis was leading in Al Anbar Province was ambushed by insurgents. Twice he braved heavy fire to aid wounded Marines. His Silver Star citation also credits him with “eliminating an enemy position with his M4 carbine and M203 grenade launcher,” before a sniper shot him. He was the only member of the patrol who didn’t survive.

“Our mission is to empower veterans and families of the fallen to instill character in the next generation of Americans,” Ryan said, a bit exhausted from her own appearance on “The View,” which began with one of the hosts mistakenly crediting Rumsfeld for starting the Travis Manion Foundation (it was started by Ryan’s family). “We’re redefining America’s national character, and we’re able to do that by highlighting our returning veterans and families of the fallen as sources of strength and resilience, and showcasing them as civic assets within their communities.”

This idea — that veterans are “civic assets” — is at odds with the narrative that’s prevailed since the start of the war on terror, which have yielded a staggering rate of post-traumatic stress disorder cases (roughly a third of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans who’ve applied for permanent disability have been diagnosed with PTSD). Hollywood doesn’t make movies about soldiers coming home and assimilating back into society as more capable versions of their pre-war selves. Stories about veterans mentoring kids in low-income neighborhoods don’t typically make the news. Even for the winners, war destroys the mind and body, or so goes the conventional wisdom. Before being accused last year of wasting donation dollars, the Wounded Warrior Project was one of the largest — if not the largest — veterans charities in the nation. The Travis Manion Foundation has managed to achieve comparable success since its founding in 2008, but with the almost opposite message, which Ryan sums up as: “Veterans are incredibly valuable to this country.”

The Rumsfeld Foundation provides grants to about 20 different military and veteran charities every year. But it has maintained a specially close relationship with the Travis Manion Foundation for more than half a decade. This raises an obvious question: Does Rumsfeld feel a certain sense of obligation toward the post-9/11 generation of vets — the young men and women he sent to war on two fronts, and without a clear objective?

“No, I’ve never distinguished it that way,” Rumsfeld said. “My dad served in the Navy. I served in the Navy. I served in the Pentagon a couple of times. So, I don’t know if I’ve ever thought of it as generational. I think that all the people who’ve served deserve the respect and support of the people of the country.”

Earlier, Rumsfeld had wrapped up his interview on “The View” by promoting an Air Force pilot to the rank of lieutenant colonel. The pilot, a man in his 40s, had been wounded during the Second Battle of Fallujah, an operation that Rumsfeld oversaw as secretary of defense, which endures as the bloodiest engagement of the entire Iraq War. For six weeks, coalition troops fought house-to-house, and sometimes hand-to-hand, until every block of the city was cleared of the estimated 4,000 insurgents holed up there. By the time the dust settled, 82 Americans were dead, nearly 600 were wounded, and nine Marines had earned the Navy Cross. As the battle was getting underway, Rumsfeld told reporters that success in Fallujah would “deal a blow to the terrorists in the country and should move Iraq further away from a future of violence to one of the freedom and opportunity for the Iraqi people.” Of course, nothing went according to plan. And there will be no apologies.

Despite his philosophical bent — brilliantly captured in “The Known Unknowns” — Rumsfeld is not eager to reflect on whatever mistakes may or may not have been made during the Bush years. While many Americans supported the war out of patriotism, Rumsfeld saw their acquiescence as a sign that the administration was on the right track. “For someone to have the characteristics of a leader, there have to be followers,” he said, as we waited for the check. “And the only way there’s going to be followers, is if the leader is doing things that have merit, that are persuasive to others. Why else would someone follow somebody if they didn’t think the individual was doing something worthwhile, going in the right direction?”

Then, after a pause, he added: “I’m reading a book on Genghis Khan right now, and he was a leader. A different kind. So, it’s not as though there’s one model for leadership.” I pointed out that under Khan, the Mongols had laid siege to Baghdad. “Yes, he went everywhere,” Rumsfeld said. “It was amazing. Just amazing.”

Lunch was followed by a trip to Yahoo! News headquarters in Times Square for another on-camera interview about the app and Rumsfeld’s work with the Travis Manion Foundation. But again, the conversation focused primarily on the scandals engulfing the White House: Trump, the Russians, Comey. Is this another Watergate? (Rumsfeld called the comparison a “big reach.”) The anchor, Bianna Golodryga, was focused and professional, asking smart, hard-hitting questions, one after another, and keeping the interview on track whenever Rumsfeld tried to leverage his old age or charm. Still, she came up empty-handed.

I expected Rumsfeld to be flustered after the interview, or at least annoyed. But he wasn’t. There was a twinkle in his eye. He was glowing, like a champion wrestler stepping off the mat. “Wow,” he said, donning his black overcoat, as his entourage closed in around him, umbrellas ready, giving me looks that let me know my time with Rummy was up. “She was great. Just really great. That was a lot of fun.”