Welcome to That One Scene, a semi-regular series in which Task & Purpose writers wax nostalgic about that one scene from a beloved (or hated) military movie. This article was originally published on Dec. 8, 2020.

Being in the military or the intelligence field isn’t like the movies. Most soldiers aren’t kicking in doors all day and real spies are not ordering their martinis shaken, not stirred. Instead, they’re often dealing with the bureaucratic bullshit that most other government workers face, like what the heck happened to my last paycheck, and why is my boss such an a-hole?

Perhaps no film captures this reality better than the 2007 Cold War drama “Charlie Wilson’s War,” which depicts the real-life “blue collar James Bond” of Gustav ‘Gust’ Avrakotos (played by Phillip Seymour Hoffman) as he dukes it out with his supervisor over his next assignment.

The film offers an on-screen success story for the CIA in detailing Operation Cyclone, the agency’s covert effort to beat the Soviets in Afghanistan. Boosted by an infamous Texas congressman of ethical fluctuation, the CIA delivered crucial surface-air-missiles and other weaponry to Afghan freedom fighters who kicked the Soviet Union out of the country, and by some accounts, helped hasten its ultimate downfall.

But the operation’s humble beginnings, according to the incredible three-minute scene directed by Mike Nichols, seemingly began in a well-lit office at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

[embedded content]

“Okay, I know it was difficult for you to come in here hat in hand, that’s not the kind of upbringing, I guess is the word, that’s not the kind of man you are,” says a man known only as Cravely (played by John Slattery), seated behind a desk and smoking a cigarette.

Standing in front of him is Avrakotos, a heavyset man sporting a mustache and large eyeglasses. As Avrakotos silently scowls and stares, Cravely urges him to go ahead and apologize (for what, we’re not sure): “We’ll call it water under the dam and we’ll go about our business,” he says, screwing up the actual phrase.

Avrakotos’ response: “Excuse me, what the fuck? What the fuck are you talking about?” It’s clear there’s been a mistake. Both say that Clair George, the legendary CIA deputy director of operations during the administration of President Ronald Reagan, said the other person would apologize.

“You told me to go fuck myself. I’m supposed to apologize to you?” Cravely asks.

(At this time, the pair are briefly interrupted by a repairman who’s fixing a window that was broken the last time Avrakotos visited his boss. This becomes relevant in a few moments.)

“The Helsinki job was mine!” Avrakotos screams at his boss, now the director of European Operations, telling him that “promises were made” that he’d be the next station chief in Finland. “Not by me!” Cravely shoots back.

We’re now about one minute into the scene when Hoffman’s Avrakotos launches into a masterful soliloquy that captures both the audience’s attention and dozens of CIA employees now listening outside the office.

“I’ve been with the company for 24 years! I was posted in Greece for 15! Papandreou wins that election if I don’t help the Junta take him prisoner! I’ve advised and armed the Hellenic Army! I’ve neutralized champions of Communism! I’ve spent the past three years learning Finnish, which should come in handy here in Virginia! And I’m never ever sick at sea! So I wanna know why I’m not gonna be your Helsinki station chief.”

“You’re coarse,” Cravely says.

“Excuse me?”

“For Helsinki, I need someone with diplomatic skills. You don’t have them.”

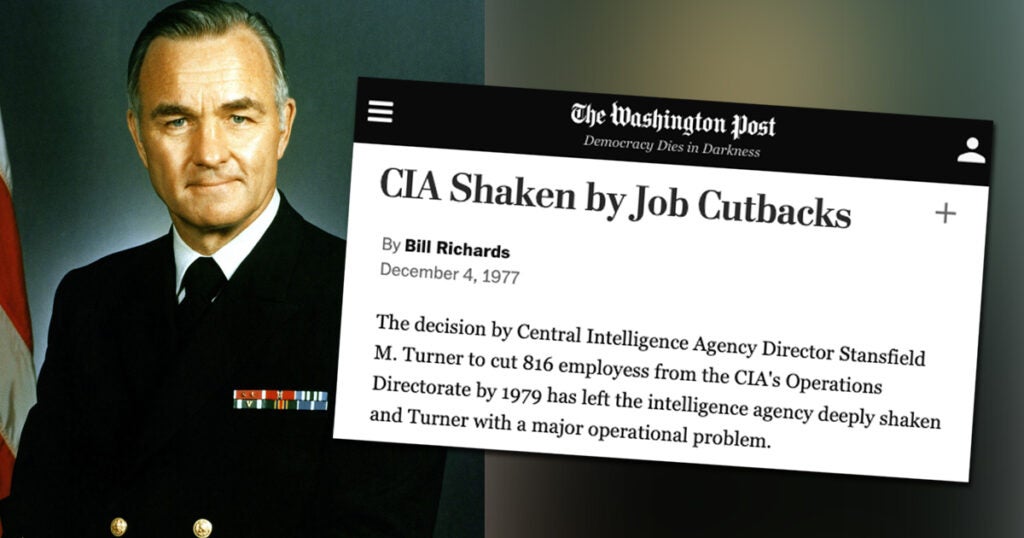

The argument continues as Avrakotos mentions 3,000 agents who were fired by Stansfield Turner, President Jimmy Carter’s deeply-unpopular CIA director. Most critics of Turner’s cuts to the clandestine service (which were actually closer to 800) called it the “Halloween Massacre.”

“Let me ask you, the 3,000 agents Turner fired, was that because they lacked diplomatic skills as well?” Avrakotos says, speaking up onscreen for many CIA officers who angrily dished to the press at the time. “The 3,000 agents, each and every goddamn one of them first or second-generation Americans. Was that because they lacked the proper diplomatic skills, or did Turner not think it was a good idea to have spies who could speak the same language as the people they’re fucking spying on?”

“Well, I’m sorry, but you can hardly blame the director for questioning the loyalty to America of people that are just barely Americans in the first place,” Cravely sneers back, implicitly questioning the loyalty of Avrakotos, an American-born son of Greek immigrants who joined the CIA in 1962.

So, he breaks the window — for a second time — after nonchalantly asking a nearby handyman for his hammer.

“My loyalty!” Avrakotos says, glass shards still falling to the ground. “For 24 years people have been trying to kill me! People who know how. Now do you think that’s because my dad was a Greek soda pop maker? Or do you think that’s because I’m an American spy? Go fuck yourself, you fucking child!”

It’s simultaneously the best introduction of a character and the greatest comeback to an asshole boss ever. And though it’s a movie that takes some liberties with the truth, there’s a surprising amount of authentic history jam-packed into it.

Despite Avrakotos’ framing of the CIA’s accomplishments in Greece, history paints a slightly less rosy picture. Though their efforts were successful, the agency helped engineer a military coup against the democratically-elected government in 1967, leading to a fascist regime that would ultimately fall in 1974. A year later, a Greek terrorist shot and killed CIA station chief Richard Welch, and Avrakotos, whose name was exposed along with Welch’s, was on their radar. He left the county in 1978.

For his efforts and working-class demeanor, The Washington Post dubbed him a “blue-collar James Bond.” And he indeed was “coarse” in real life, as Cravely described him: “Mr. Avrakotos once showed a photograph of a colleague who crossed him to an old Greek woman and requested that she put a curse on him,” the Post wrote of the long-time agent after his death in 2005.

“You might say he was rough around the edges,” recalled a longtime friend. “He was comfortable using the F word.”

But Avrakotos’ willingness to call out bullshit also earned him a description as a Greek-American “with a profane tongue and bare-knuckle character.” Or as the film’s director described him, he was a guy “who tell[s] the truth casually and constantly.”

It was after this meeting that Avrakotos began his journey from taking his anger out on his boss to taking his anger out on the Soviets, eventually finding a spot on the Middle East desk at the CIA.

“If it’s really true that you have nothing to do,” John McGaffin, head of the Afghan program at the CIA, told Avrakotos at the time. “Why not come upstairs? We’re killing Russians.”

Avrakotos became section chief of an area that included Afghanistan and teamed up with former Army Special Forces weapons sergeant Mike Vickers, who also played a key role in the arming of the Afghan mujahideen.

“Long after the congressman became enamored of the Afghan cause and began using his position to add funds to the CIA assistance program that were not requested by the administration — a most unusual move — Avrakotos joined the program at CIA,” agency historian Hayden Peake wrote in a 2007 review of the book by George Crile upon which the movie is based.

“From then on, things really began to move,” Peake added. “With the help of a talented staff that never received adequate recognition, the CIA started providing the kind of weapons the Afghan warriors needed to win the war. The Enfield rifles that had kept them in a high-casualty, Russian-harassing mode were relegated to the waste bin. The Afghans were trained and supplied with Pakistani help, and the death-dealing Soviet HIND-21 helicopters began dropping out of the sky.”

As Crile wrote, “Throughout his Afghan tour, Avrakotos did things on a regular basis that could have gotten him fired had anyone chosen to barge into his arena with an eye toward prosecuting him,” adding that “he was brutally worldly wise” and “keenly aware of the internal risks he was taking” but made it difficult for his enemies to pin him down.

Still, Avrakotos’ truth-telling ultimately cost him. As the Post noted, Avrakotos’s career stalled soon after he rightly opposed the CIA’s illegal arms-for-hostages scheme, which saw more than 1,500 missiles sold to Iran while the proceeds were funneled to rebels in Nicaragua. President Reagan also hoped the arms sales would win the release of Americans taken by Iranian-backed terrorists in Lebanon.

The plan didn’t exactly work out. Instead, the “Iran-Contra Affair” became the biggest scandal of Reagan’s presidency and led to the convictions of a half-dozen top officials, including Marine Lt. Col. Oliver North, an NSC staffer, whose conviction was overturned on a technicality.

Avrakotos was later reassigned to Africa and retired in 1989, though he did another contract stint for the agency from 1997 to 2003. And Phillip Seymour Hoffman earned an Academy Award nomination for his portrayal of the grizzled CIA veteran who “oversaw the largest covert operation in the CIA’s history” — all because a guy was “too coarse” for Helsinki.

More great stories on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.