The Air Force may call to mind fabulous images of fighter jets, stealth bombers and enormous transport planes in flight. But it takes elbow grease to keep those aircraft aloft, and one of the less-glamorous tasks involved is the ‘FOD walk’ for foreign object debris along the flightline, a slow trek up the runway where airmen crane their necks down to look for spare bolts, washers, pebbles and other debris that could damage an aircraft by being sucked into its engine intake.

Usually, on a sprawling Air Force base with thousands of people working there, FOD walks are conducted by aircraft maintainers or other airmen with a flightline badge. But when your base only has 70 people working on one airstrip in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, everybody chips in to help.

“A FOD walk is the least glamorous thing you can do: you walk around, you pick up rocks, it’s pretty boring,” said Capt. Austin Sewell, who was in charge of the tiny airstrip on the island of Tinian during an exercise in July. “Normally that’s something only maintainers have to do. But man, we had comms guys, medical, weather, public affairs, and the pilots themselves walking around cleaning up this flight line to make sure it was good and useful.”

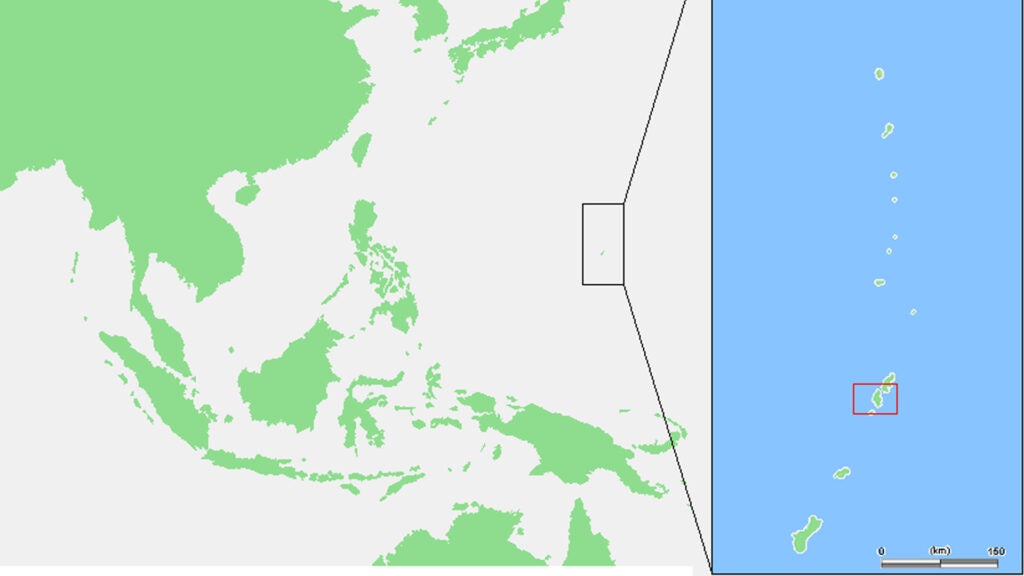

It may seem small, but the FOD walks on Tinian represent a moment of independent, small-unit teamwork that airmen rarely experience elsewhere in the Air Force. It was Sewell, Master Sgt. Daniel Fajardo and just a few dozen other airmen who were tasked with launching and recovering aircraft from Tinian during Operation Pacific Iron 2021, an exercise where 800 airmen and 35 aircraft from bases around the Pacific gathered around Guam and Tinian to simulate standing up a large-scale air operation about 1,800 miles away from the nearest continent.

Most Air Force bases are city-sized complexes with thousands of employees, heaps of supplies, and layers of infrastructure and bureaucracy to keep the whole thing running. By contrast, Sewell had pinned on the rank of captain just two weeks before the start of Pacific Iron, and now he found himself in command of a one-runway, 70-man airstrip that F-15E Strike Eagle attack jet pilots were counting on for fuel and support so they could patrol hundreds of miles of open ocean surrounding them.

“Normally a base commander is a colonel and the senior enlisted is normally a chief,” Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach, the head of Pacific Air Forces, told reporters about the exercise at a conference in September. “So we’re asking a very young captain and a relatively young master sergeant [to be] the leadership at the spoke.”

Why leave such responsibility in the hands of a junior officer and a master sergeant? It may be the key to beating China in a possible war in the Pacific. The large bases to which the Air Force is accustomed present juicy targets for hostile missiles, and there aren’t many of them in the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean. Instead, the Air Force is working hard on Agile Combat Employment, which is Pentagon-ese for learning how to work on smaller airstrips with smaller crews than the service is used to working with.

Still, it’s not the first time the Air Force has operated like this. Back in World War II, when the service was part of the Army, it employed more than 120,000 aviation engineers who built, improved or maintained 1,435 airfields in 67 countries.

“By V-E Day on 8 May 1945, the IX Engineer Command built or refurbished 241 airfields in France, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and Germany with a peak production of opening a new airfield every 36 hours,” wrote Air Force officers in an essay for the March edition of Air & Space Power Journal.

“Each base you build will be a stepping stone toward victory,” Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, one of the founders of the Air Force, told the engineers. “Because the faster you move and work, the faster ‘the air’ moves and gets at the enemy—up close where it counts.”

The same principle applies today. Only instead of stepping stones, the Air Force calls them hubs and spokes. The ‘hubs’ refer to larger, better-supplied bases like Andersen Air Force Base, Guam, while the ‘spokes’ involve tiny airstrips like the one on Tinian this summer.

“We’ve surveyed almost every piece of concrete in the Pacific for whether we can use it for a hub or a spoke,” Wilsbach told reporters.

For non-Air Force types wondering ‘what does this have to do with me?’ Well, even wars fought on the ground or on the sea likely need air cover to fight off attacking enemy aircraft or to strike enemy positions. But that air cover will have a hard time flying all the way from the continental U.S. or Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, or even Andersen Air Force Base on Guam, depending on where in the Pacific the Marines or Army are fighting.

That’s where smaller airstrips like Tinian come in. The island is a long way from Mountain Home Air Force Base, Idaho, where Sewell, Fajardo and many of the other Tinian airmen are based. But one of the goals of Pacific Iron was to see if America’s airmen could do what they do best without a dining facility, a post exchange, and all the other trimmings of a large base.

“The whole point is you continue to operate as if everything is normal,” Sewell said. “Folks keep launching out of Guam, we’d launch out of Tinian, they’d meet up, play war games in the air and then land back at their respective locations and we fix them, turn them and keep operating that way.”

And they had to do it fast: when the Mountain Home crew took off from Guam in a C-130 transport plane bound for Tinian, the F-15s that they would have to refuel were already airborne. Sewell’s airmen would have to land, unload their cargo from the plane, sort out plans with the Tinian airport authorities and set up a fuel bladder full of jet fuel before the fighters ran out of gas. Then the airmen would catch the landing fighter jets, do some maintenance on them and get the air crew back in them ready to fly as soon as possible. Somehow they got it all done within three hours of landing on Tinian.

“We launched those airplanes again within about three hours of being on the ground, which for us was super cool and indicative of an ability to pick up, get to a new location, refuel, reload bombs if we had them for this exercise, and then continue fighting the war all within a few hours,” Sewell said.

Fajardo agreed, saying that those three hours were an intense, but rewarding experience.

“Setting up and operating out of a small airport terminal with minimal supplies, equipment, people and so forth is almost like the Air Force dream,” he said. “Like, this is what we joined the service to do — these kinds of things where we operated on our own, away from the main hub. It was definitely an adventure.”

It can’t be overstated how small the Tinian base was compared to most Air Force operations, such as Sewell and Fajardo’s home base at Mountain Home, where about 5,000 people work. The contingent of airmen at Tinian included most of the jobs necessary for running a huge base, just on a much smaller scale.

There were maintainers to fix the aircraft; security forces [the Air Force equivalent of military police] to guard the perimeter; communications techs to keep everyone connected; aircrew flight equipment specialists to look after the oxygen masks and parachutes for pilots; medical technicians to keep everyone healthy; weather experts with their eyes on the sky; logistics airmen to keep the planes gassed up and supplies in order, and public affairs airmen to take pictures of the whole thing.

“It was essentially 5% of a base,” Sewell said. “We had a little bit of representation from almost every entity that you would need to run a base.”

Yet for a small airstrip to work with only a skeleton crew of airmen, each of those airmen needs to be a Swiss Air Force Knife, so to speak. They have to be able to guard the airstrip from intruders, refuel aircraft coming in from a sortie, lend a hand patching up holes in fighters and yes, even do an occasional FOD walk. Luckily, Sewell and his crew were more than ready for it.

“Everybody was like ‘hey, how can I help?’” the captain recalled. “We had comms troops that were driving forklifts so that the maintainers could focus on the airplanes. We had security forces coming out saying ‘hey, I’ve done this before, can you retrain me real quick?’ And then they would help chock the airplanes and launch them out.”

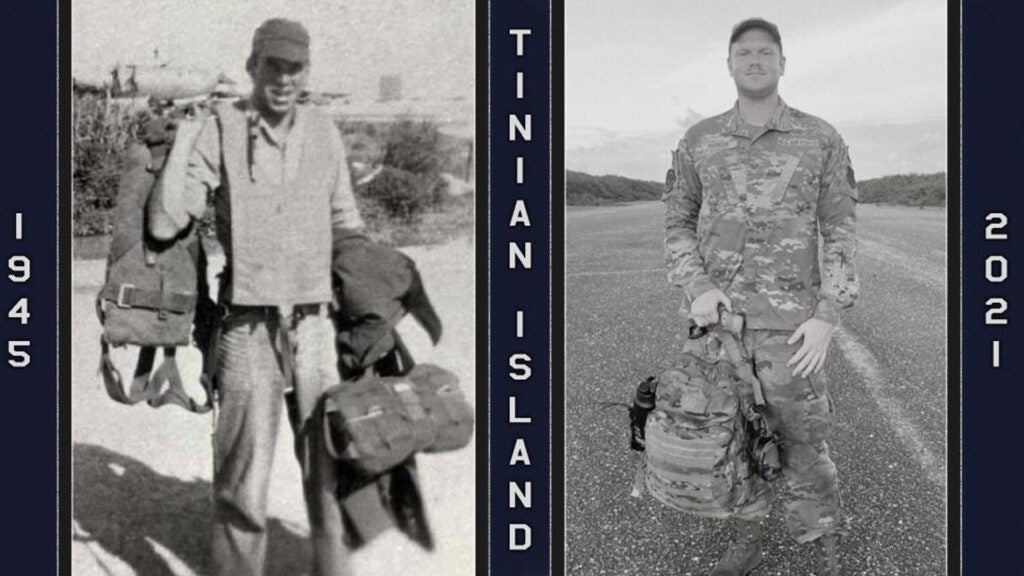

The Pentagon-ese term for airmen knowing how to do multiple jobs is ‘multi-capable airmen,’ and several of the Tinian crew had a personal drive to be as multi-capable as possible. Sewell mentioned one airman, Tech Sgt. Parker Dawson, whose grandfather was stationed on Tinian during World War II, so “it was very important for him to get out there and make 100% sure that he would be an asset.”

A specialist in electrical and environmental systems, Dawson picked up how to refuel jets, Sewell said. Other airmen learned all about aircraft structures so they could help patch them up. Most importantly, they all learned to work together to make the tiny airstrip purr. Sewell said it was a bit like a camping trip, where everyone was expected to “pull their own weight.”

It also helped that airmen were free to pull that weight without as much fear of a supervisor pulling rank. In other words, because the airmen were out on their own, they were more free to work without the overhead bureaucracy you might find on a large base.

“I’m very excited and hopeful that that is kind of a way that we’re moving: really empowering folks at younger ranks to make important decisions and to just act,” the captain said. “I don’t know how to word it properly, but a lot of times you go directly through the chain of command before making any decision. And we have been extremely empowered at this base to make decisions at my level. In the Pacific, it was even more magnified.”

Wilsbach hopes that the rest of the Air Force takes note of the leadership Sewell, Fajardo and the rest of the crew showed in Pacific Iron.

“In their day-to-day training [airmen] need to be equipped and have opportunities to develop that leadership so that when we send them out to a small island in the Pacific by themselves, they can make those decisions,” he said.

The teamwork at Tinian expanded beyond just the airmen involved. Though Tinian might feel like the middle of nowhere to Americans, it is home for the 3,000 or so people who live there. Sewell and Fajardo were happy to report that, in between cranking out sorties, they had a great time showing off the jets to local school kids, using machetes to beat back some overgrown jungle that had encroached on the school building, and sharing meals and stone-and-sling throwing tournaments with Tinian families during weekly beach parties.

“At times it was a little difficult with the communication barrier, but at the end we all came together and made it work,” Fajardo said.

Sometimes the little things like that are all you need.

“I can’t get over how cool” the exercise was, Sewell said. “It was super stressful, a very difficult event that everyone went through. But at the same time we got to go through some small unit dynamics and feel like a team. It’s what I thought the Air Force was going to be when I joined.”

More great stories on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.