This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.

A laboratory with real stakes.

That’s what a former commander of one of the Army’s top-tier special operations units called Afghanistan. It was a place, over two decades of war, where a generation of special operations units honed their skills carrying out missions ranging from kill-or-capture raids to training Afghan soldiers. With the war in Afghanistan officially over, the U.S. military—especially the special operations community—sees an uncertain future.

“We learned a lot of stuff [in Afghanistan],” says the former Army commander, who spoke under condition of anonymity because he still serves in the military. “We’ve used the lab to hone the tools, but you’re going to pay a penalty. There will be a dividend that we’ll get back in terms of pressure on the force. There is a cost to being constantly deployed. There is also the cost of not being directly engaged in the job you signed up to do all the time.”

America’s secret warriors—who cemented themselves as the nation’s “go-to” force—will need to find that balance in a world where the global order has changed. They will need to pivot to a fight that includes more than just insurgents and terrorists. Experts, from the top of the chain of command to the team room, all agree terrorism isn’t going away, but the world they spent the last two decades fighting has.

SOF is experiencing an identity crisis, says David Maxwell, a retired U.S. Army Special Forces colonel who specializes in irregular, unconventional, and political warfare. “Joint Special Operations Command’s mission of counterterror is never going away. It is necessary. We’ve raised our counterterror capability to an exquisite level. We’re going to sustain and protect that. The other side is harder to describe.”

But life after America’s longest war for special operations is one of opportunity and provides a return to smaller missions that are just as strategic, if not more, than the big, headline-making battles of the past 20 years. Special operations forces (SOF) will build partnerships with militaries around the world and focus on great power competition—namely countering China and Russia, even as they change how they fight from capture and kill attacks to psychological warfare and influencing local politics.

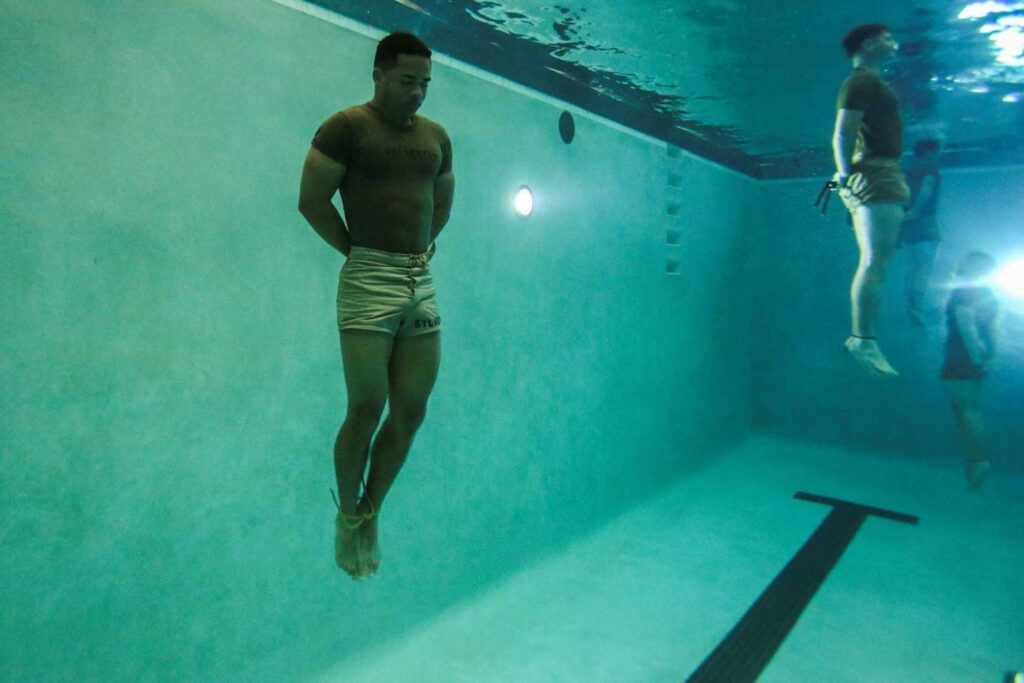

SOF units are made up of service members from every service. In the Navy, they’re SEALs. The Army has Special Forces—nicknamed Green Berets because of their iconic hats, Rangers, and soldiers specializing in civil affairs and psychological operations. The Air Force special operations is trained to rescue pilots and call in airstrikes. Marine special operations are called Marine Raiders—the nation’s newest SOF community—and can do everything from reconnaissance to commando raids.

Since the 1980s, SOF has gained prominence from pop culture icons like Special Forces soldier John Rambo in First Blood and the subsequent sequels, and shows about Navy SEALs on network TV. This came after high-profile missions like the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia, made famous by Mark Bowden’s Black Hawk Down; operations against rebels in Colombia; leading the assault in Afghanistan on horseback; and finally killing Osama bin Laden in a daring raid in Pakistan in May 2011. SOF has become the icon of the war on terrorism, and, arguably, the bearded, night vision-wearing SOF operator is a new American idol.

Even as special operations forces retrain for the changing mission, the road map isn’t new: We’ve been here before. They’ll go back to training foreign armies like they did in Colombia and across the African continent. They’ll gather intelligence and track suspected terrorists and conduct violent raids, but unlike what they did during the war, they won’t return to a firebase in the target country. Once again, SOF fighters will sink into the shadows, their mission needing more intellect than brawn.

“They’ll play on the edge of empire,” a former Marine Raider says.

‘You’re Not Going to Take China in China’

The Pentagon has already dubbed it “over-the-horizon operations,” alluding to drone strikes, cyberwarfare, and small-unit raids. The cadence of operations would resemble American operations in Yemen and Somalia, where drone strikes and lightning-fast raids with no enduring presence on the ground were the order of the day. This also plays into bigger strategic moves against China and Russia, several sources told The War Horse.

Across the globe, China is involved in everything from resource extraction—especially rare earth metals—to infrastructure projects like roads, dams, and energy and agriculture projects. China was one of the first countries to reach out to the Taliban government in hopes of exploiting Afghanistan’s estimated $1 trillion to $3 trillion in rare earth metals.

The Chinese have repeated this playbook in Africa and Latin America, leading to massive investment in exchange for mining and access to commodities. Since 2008, China has provided more than $35 billion in loans to Latin American countries, Shamaila Khan, director of emerging market debt at Alliance Bernstein, told CNBC.

“You’re not going to take China in China,” says an intelligence sergeant who worked with tier-one units. “You’ll take China on in Africa, Afghanistan, and in Iran and Syria.”

The danger of terrorism also serves as a constant threat. SOF is arrayed to fight both with kill and capture missions, but also by partnering with foreign militaries to increase capability, several sources told The War Horse. The performance of the Afghan military at the end of the war notwithstanding, SOF has had some success mentoring militaries in Africa and Latin America, especially in Colombia versus the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Columbia.

It just takes a long damn time to do it right. That’s why retired Admiral Bob Harward, a SEAL who led special operations units in the invasions of both Afghanistan and Iraq, thinks Special Operations Command (SOCOM) should take the reins and lead the way.

“Ever since 9/11, what was the job of SOCOM?” he says. “They were responsible for synchronizing the war on global terrorism. But it gave them no real authority. Terrorism is going to be a growing problem again, not a shrinking problem. And all the services and everyone else wants to focus on China. I think this is the perfect time for the U.S. government to designate SOCOM as the lead on the global war on terrorism.”

In addition to staying focused on a persistent threat, this move would keep SOF engaged with partners across the globe. Retired Lt. Gen. Kenneth Tovo, former commander of Army Special Operations Command, said SOF is uniquely capable of getting on the ground, training partner forces, and understanding issues in the “human domain.” Small teams of Special Forces or SEALs are the canary in the coal mine. When something does happen, the relationships and ground truth are there, according to Tovo.

“You need to have presences,” Tovo says. “We’re going to always be a crisis action force. We’ve developed relationships and partners to help develop a U.S. reaction.”

‘Direct Conflict Doesn’t Make Sense’

SOF exists to fight in uncertainty, but it’s about to enter a world of competitors and state actors looking for an adjusted world order. One expert said the current order resembles the 19th century—not the dual-superpower Cold War. Multipolar. Global with regional actors and terrorism.

“If that is the case, your next assumption is direct conflict doesn’t make sense,” the former Army commander said. “When they do need to act, it will be fast and limited and offset our advantages. SOF will be the deterrent. You’re going to deter through shoulder-to-shoulder operations. Win by points, not by knockout.”

Maxwell says SOF is the military’s best tool to solve complex military problems and create issues for the nation’s adversaries. He imagined a scenario where local dissidents are organized and resourced to carry out operations in Russia or China. SOF can leverage populations to exploit cracks and fissures that can generate challenges for the nation’s opponents.

“I’d make a case for resistance in Afghanistan,” Maxwell says. “It is going to emerge. There is a lot of application for that potential. Popular resistance against Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea.”

Called the resistance operating concept, the goal is to make sure American allies can resist an invasion from a power like Russia or China. That means making sure SOF and resistance groups can plan together.

Otto Fiala and others explained the concept in a two-part July podcast produced by the 1st Special Forces command. It looks to past examples, such as the French Resistance during World War II and stay-behind networks put in place to counter a Soviet invasion during the Cold War.

“An adversary knowing that you have this resistance capability, there is an organization that exists, and that your people are willing to resist is a strong message of deterrence,” Fiala said during the podcast.

‘This Is Really Warfare of the Mind’

But SOF’s hardest mission might be online.

“You’ve got to be fit and tactically proficient,” Tovo says. “But this is really warfare of the mind. It is less about if you can shoot three-inch dots at 100 meters.”

A 1951 paper examining psychological warfare in Korea concluded it was an inexpensive, effective weapon that is bound to prove more effective as we continue to learn to perfect our technique.

The Information Warfare Center at Fort Bragg, which opened in August, stands as another step to improve technique. It will consolidate the Army’s psychological operations capabilities so it could provide “influence artillery” to forward units and teams, said Col. Ed Croot, chief of staff at 1st Special Forces Command, during a virtual presentation in February for AFCEA TechNet Augusta, according to C4ISRNET.

“There’s a unique threat audience, a unique friendly audience, a unique neutral audience that has to do with that influence and information piece,” Croot said during his presentation. “It’s extremely difficult to be able to move fast in that space.”

The meme is the new leaflet, Maxwell says.

“It is easier to put a hellfire on the forehead of a terrorist than put an idea between his ears,” he says. “We should think not in terms of dropping commandos into China to destroy targets, but indirectly take on China in the influence realm.”

But one of the biggest shifts for SOF units might be the absence of a war.

Tovo said down in the team room there is a lot of hand-wringing because most of the force has a lot of combat time, but that will shift to peacetime engagement as SOF positions itself for strategic competition. This pause might lead to a much-needed reset. A former Marine forces special operations command officer said special operations became a hammer when it should have remained a scalpel.

“You want to kick down doors, shoot bad guys in the face,” he says. “We’ve vastly relied on SOF on the perception of reliability. We’ve become so risk averse. An Army 11B or Marine rifleman can do that job. Killing people is easy. The hard part is modifying human behavior.”

‘We’re Overdue for Something to Wake Us up Again’

And it isn’t just the behavior of the enemy. Cleaning up SOF culture will likely need to happen as well after several high-profile incidents that have exposed issues in SOF culture.

In 2019, a SEAL platoon from SEAL Team 7 was sent home from Iraq after allegations of drinking and sexual assault, and after six SEALs tested positive for cocaine and other banned substances. Chief Special Warfare Operator Edward Gallagher, a former member of SEAL Team 7, faced a court martial for war crimes charges including murder, but was only convicted and later pardoned for posing for a picture with a dead body. Two SEAL Team Six operators and two Marine Raiders were convicted or pleaded guilty in events surrounding the strangulation death of a Special Forces soldier in Mali in 2017.

Harward says special operations units—particularly the tier-one units like SEAL Team Six and Delta Force—created a caste system with those units acting above their parent conventional forces.

“You look at some of the premier units, their longest deployment is four months,” Harward says. “They train and stay in nice hotels, they travel, they have a pretty good life, where some of the heavier lifting is done from those guys who do full six-month deployments. We recognized when we first created some of these organizations, we were having those problems. I don’t think we’ve proactively have addressed that in the fashion it needs to be.”

A former intelligence sergeant said every decade, SOF restructures to better position itself to address current threats.

“We’re overdue for something to wake us up again,” a former intelligence sergeant said. “We’re operating in a more complex world. We need to pull back and restructure and kill some of the current organizations and start something new from scratch.”

What that new organization looks like is unclear, but it will face a new world where the meme is as important as a gun and where the adversary could be a peer.

+++

This War Horse feature was reported by Kevin Maurer, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Ben Kalin, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar.

Kevin Maurer is an award?winning journalist and the bestselling coauthor, with Mark Owen, of No Easy Day: The Firsthand Account of the Mission That Killed Osama bin Laden; No Hero: The Evolution of a Navy SEAL; and, with Tamer Elnoury, American Radical: Inside the World of an Undercover Muslim FBI Agent. He has covered the military—particularly the airborne and special operations forces—for 17 years, including embeds in Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti, and east and central Africa. He lives in North Carolina.

More great stories on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.