On a treacherous mountain ridge near San Terenzo, Italy on April 21, 1945, Daniel Inouye was a force not just to be reckoned with, but one of sheer willpower.

The 20-year-old Army second lieutenant had been shot while advancing on an enemy machine gun nest in the final months of World War II. Hit in the torso by a sniper’s bullet and bleeding, Inouye kept fighting, only to be wounded again, this time by an incoming grenade that exploded on impact, shattering his right arm. And then he was hit once more, for a third and final time, when he was shot in the leg and rendered unconscious.

Then he woke up, and kept going. He simply would not stop.

For his actions that day, Inouye was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which was later upgraded to the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for battlefield bravery, on June 21, 2000. He went on to become the first Japanese-American elected to Congress, and served in the Senate for nearly 50 years until his death on Dec. 17, 2012 at the age of 88 from respiratory complications.

It seems fitting then, that the U.S. Navy has decided to name its newest Arleigh Burke-class missile destroyer after a soldier whose life, both in and out of uniform, was punctuated by adversity, and defined by a will to endure, and then triumph.

On Wednesday the official Twitter account for the U.S. Pacific Fleet celebrated the announcement, along with photos of the soon-to-be named USS Daniel Inouye. The destroyer is expected to be officially commissioned on Dec. 8, and will be based out of Hawaii’s Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, according to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

Born on Sept. 7, 1924 to Japanese immigrants, Inouye grew up in Honolulu back when Hawaii was a territory of the United States. According to the National World War II Museum, from a young age, Inouye had a generous spirit and he actively sought out opportunities to help others. In high school he volunteered at the Red Cross, and fostered ambitions of becoming a surgeon.

Then on Dec. 7, 1941, everything changed: The Imperial Japanese Navy bombed Pearl Harbor.

In a 2015 oral history interview with the World War II Museum, Inouye described the events of that day. Like he did on most Sundays, the 17-year-old high school senior got ready for church, but as he put on his shirt and tie, he heard a broadcaster on the radio announce: Pearl Harbor was under attack by the Japanese Navy.

As Inouye and his father stepped outside their home, they watched as Japanese aircraft pummeled the headquarters of the Navy’s Pacific Fleet. “We looked towards Pearl Harbor and puff! All the smoke. And you could see puffs of the anti-aircraft shells exploding. And then, all of the sudden, three aircraft flew right over us. Green color with the red dot in the wing. I knew my life had changed,” he said.

Within moments Inouye was racing to the Red Cross aid station to tend to civilians and sailors who were wounded in the attack. It may have been the first time that Inouye ran toward danger to help those in need, but it would not be the last.

[embedded content]

After graduating from high school, Inouye attempted to enlist in the Army in 1942, but he was denied outright due to his Japanese heritage, according to the National World War II Museum.

“Though I was a citizen of the United States,” Inouye said. “I was declared to be an enemy alien and as a result not fit to put on the uniform of the United States.”

On Feb. 19, 1942 President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which led to the incarceration of more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry, most of them American citizens, in internment camps. The overwhelming percentage of Japanese-Americans in Hawaii prevented the order from being applied there, as it would have had a devastating economic impact on the island.

It is one of the bitter ironies of the World War II era: As the United States waged a war against fascism and tyranny abroad, its government put its own citizens behind bars based solely on their ethnicity. Yet Americans of Italian or German descent did not face the same treatment from the government, despite the fact that both countries, like Japan, were at war with the U.S.

Even so, an estimated 33,000 Japanese-Americans served during World War II. They did so at great personal risk and at incredible cost, and Inouye was one of them.

After mounting pressure, Roosevelt ordered the establishment of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team on Feb. 1, 1943, almost a year after ordering the mass-internment of many Japanese-Americans. The unit was composed of mostly second-generation Japanese-Americans born in Hawaii, and carried the motto “go for broke,” meaning to put everything on the line in the hopes of victory.

It’s a saying that the soldiers of the 442nd more than lived up to. By the war’s end, the regiment was the most decorated unit of its size and length of service. Totaling roughly 18,000 men, the 442nd earned more than 4,000 Purple Hearts, 4,000 Bronze Stars, 560 Silver Star Medals, 21 Medals of Honor and seven Presidential Unit Citations, according to the World War II History Museum.

After the 442nd Regiment was established, Inouye immediately enlisted, quitting his pre-med studies and putting his dreams of becoming a surgeon on hold in favor of a uniform and a rifle. Within a year, the young soldier had completed training and even picked up sergeant. By the summer of 1944 Inouye was at war, fighting in Italy, where he quickly distinguished himself as an accomplished marksman. Then it was on to France, where the 442nd assisted in the relief of the 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division. The campaign took a brutal toll: By the end of the fighting, some of the companies of the 442nd were down to fewer than a dozen men. Inouye’s unit was one of the lucky ones — if you can call it that. His company set off with 150 soldiers and returned with just 42 fit for duty.

In recognition of his courage under fire, Inouye was given a battlefield commission and promoted to second lieutenant. He was also awarded the Bronze Star, with a “V” device for valor.

Then in early 1945, the regiment was ordered back to Italy, and it was there that Inouye’s actions would elevate him from a standout soldier, to a living legend.

On April 21, Inouye’s platoon was tasked with assaulting a German-held ridge overlooking the village of San Terenzo. This meant advancing up a steep mountainside over uneven terrain under plunging enemy fire. To call it tough would be an understatement.

Shortly after the operation began, Inouye was shot in the stomach by an enemy sniper. By his own accounting, he hardly noticed.

“I was in charge of this platoon and as we progressed during the morning, I was shot in the guts,” Inouye said during a 2011 video interview. “The messenger walking behind me said ‘hey, you’re bleeding.’ I thought some rock had hit me or something … and sure enough there was blood, but it did not hurt. One thing about internal injuries is there’s not too many nerve endings there. So I said ‘hey it’s not bleeding too badly, so I’ll keep going.’ And then all hell broke loose.”

As the platoon made its way forward, three German machine gun teams opened fire, pinning the soldiers down, yet Inouye pushed ahead, crawling uphill, under fire, inch by inch. As he went, he shouted to his men, encouraging them, pushing them, urging them onward. The German machine gunners had the advantage of a defensible elevated firing position and the weaponry to make good use of it; it was no time to stay still. So Inouye pressed the attack, and his men followed his lead.

[embedded content]

After low-crawling to within meters of one of the machine gun nests, Inouye quickly took it out with a pair of grenades, before killing the soldiers manning the second emplacement with his Thompson submachine gun.

Then came the third and final gun position. Just as before, Inouye readied a hand grenade, but as he pulled the pin and prepared to throw it, he was spotted.

“As I drew my arm back, all in a flash of light and dark I saw him, that faceless German, like a strip of motion picture film running through a projector that’s gone berserk,” Inouye recalled. “One instant he was standing waist-high in the bunker, and the next he was aiming a rifle grenade at my face from a range of 10 yards. And even as I cocked my arm to throw, he fired and his rifle grenade smashed into my right elbow and exploded. I looked at my dangling arm and saw my grenade still clenched in a fist that suddenly didn’t belong to me anymore.”

It’s hard to imagine the grit it took to do what Inouye did next: The grenade was live, yet miraculously Inouye’s fingers retained a tight grip, despite the fact that his right arm was a mangled mess. As he yelled at his men to stay back, he pried the explosive free with his left hand, and hurled it at the German soldier.

Switching his Thompson to his left hand, Inouye then continued to lead his men further up the ridge, firing and issuing orders until he was shot once more, this time in the leg, and lost consciousness. When he came to, he saw his men gathered around him, concern etched on their faces, preparing to carry him out of harm’s way to the rear. The first words out of Inouye’s mouth were “Get back up that hill!” Those were followed closely by “Nobody called off the war!”

Inouye, refusing to be evacuated, got back up and directed his men to establish defensive positions so they could hold the ground they had fought so hard to take.

After a brutal climb up the mountain, Inouye and his soldiers had taken their objective, killing 25 German soldiers and capturing eight others. Inouye had been shot in the chest, leg, and had his right arm blown up, yet it would be hours until he made it to the field hospital.

Once there he underwent surgery and received a total of 17 blood transfusions, all without anesthesia. He had already been given morphine, and the doctors couldn’t risk administering any more. He underwent several surgeries over the next two weeks, and his arm was amputated. Inouye’s life was saved, but his aspirations of becoming a surgeon were dashed, left behind on the bloody operating table.

Like so much of his life before, Inouye’s path forward was difficult, but he persisted. He spent the next two years recovering, and during that time he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery and leadership that day on the mountain ridge, before ultimately retiring from the military in 1947 at the rank of captain.

Inouye’s story didn’t stop there, and his legacy only grew with time. After leaving the Army and graduating from the University of Hawaii in 1950 with a bachelor’s in government and economics, Inouye went on to earn a law degree from George Washington University in 1952, and spent time as a prosecutor in Honolulu, according to an obituary in the Los Angeles Times.

Then in 1959 after Hawaii received statehood, Inouye was among the state’s newly elected representatives to the House, making him the first Japanese-American to serve as a state’s representative. He went on to win a seat in the Senate in 1962, another trailblazing achievement, as he was once again the first Japanese-American to do so. Over the next several decades, Inouye remained in the Senate where he earned a reputation for morale courage.

“Everyone in the Senate not only admired Danny Inouye, but they trusted him,” then-Vice President Joe Biden said after Inouye’s death in December 2012. “We all knew he would do the moral thing regardless of the consequences — whether it was passing judgment on a president during Watergate or on another president in the Iran-Contra hearings. And Danny always remembered where he came from — and how hard his family had to struggle.”

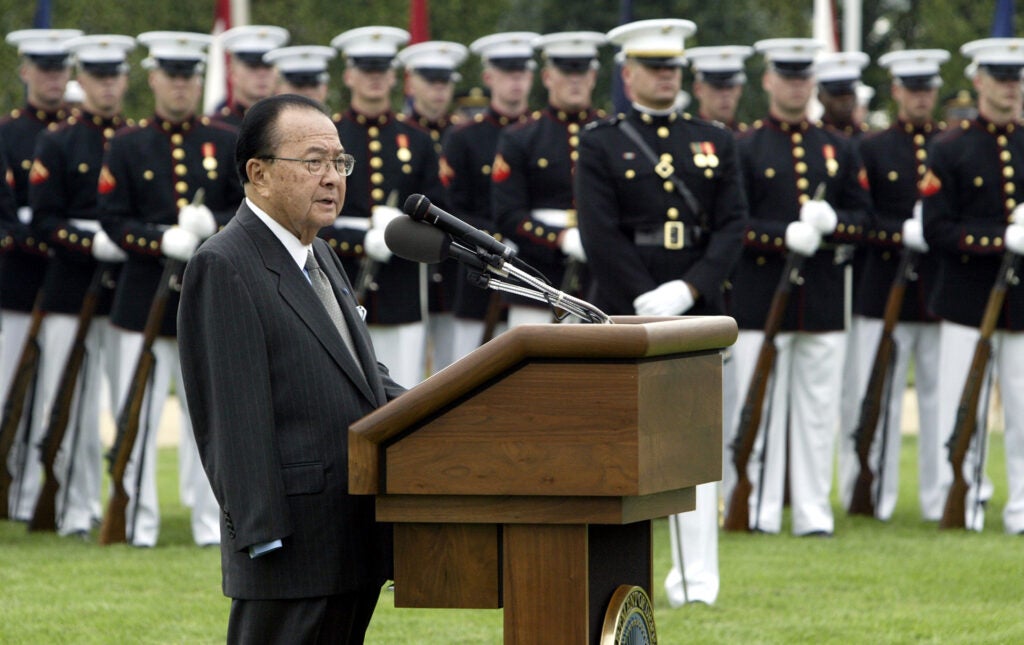

On June 21, 2000, Inouye’s Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor, which was presented to him at the White House by President Bill Clinton, 55 years after that battle.

Of his actions that day, Inouye once described his state of mind as “temporary insanity.”

“I look at the citation and I say, ‘No, I couldn’t have done that.’” But he did.

Now, Inouye joins a long list of military heroes whose names live on as U.S. Navy warships, from the USS Rafael Peralta, to the USS Jason Dunham. But warships are nothing without the sailors who crew them, sailors whose maxim “fight the ship,” means doing everything in your power to take the fight to the enemy once you’re in harm’s way.

It’s hard to imagine a more fitting namesake for a warship than a man who could get shot, blown up, shot again, and yet still manage to carry the day.

The Medal of Honor citation for Daniel Inouye can be read in its entirety below:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Second Lieutenant Daniel K. Inouye distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism in action on 21 April 1945, in the vicinity of San Terenzo, Italy.

While attacking a defended ridge guarding an important road junction, Second Lieutenant Inouye skillfully directed his platoon through a hail of automatic weapon and small arms fire, in a swift enveloping movement that resulted in the capture of an artillery and mortar post and brought his men to within 40 yards of the hostile force. Emplaced in bunkers and rock formations, the enemy halted the advance with crossfire from three machine guns. With complete disregard for his personal safety, Second Lieutenant Inouye crawled up the treacherous slope to within five yards of the nearest machine gun and hurled two grenades, destroying the emplacement. Before the enemy could retaliate, he stood up and neutralized a second machine gun nest. Although wounded by a sniper’s bullet, he continued to engage other hostile positions at close range until an exploding grenade shattered his right arm. Despite the intense pain, he refused evacuation and continued to direct his platoon until enemy resistance was broken and his men were again deployed in defensive positions. In the attack, 25 enemy soldiers were killed and eight others captured. By his gallant, aggressive tactics and by his indomitable leadership, Second Lieutenant Inouye enabled his platoon to advance through formidable resistance, and was instrumental in the capture of the ridge. Second Lieutenant Inouye’s extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit on him, his unit, and the United States Army.

More great stories on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.