President Joe Biden’s administration has pledged to finally shut down the detention center for terrorism suspects at Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, but given continued opposition from Congress it is likely that the prison will remain open for the foreseeable future.

White House spokeswoman Jen Psaki has said that Biden intends to close the detention center before he leaves office.

“He absolutely remains committed to shutting down Guantanamo Bay — something he has stated many times in the past as Vice President, running for office, et cetera,” Psaki told reporters on Tuesday during a White House news briefing.

But nearly one year into Biden’s administration, government officials have said nothing about how exactly the Guantanamo Bay detention facility could be closed, where the prisoners currently being held there would be moved to, and how U.S. officials could prosecute terrorism suspects when the current approach of using military commissions has stalled legal proceedings.

For nearly 100 years, Naval Station Guantanamo Bay was primarily known as the U.S. military’s main Caribbean outpost. Many Americans were only aware of its existence of ‘Gitmo’ because of the 1992 movie “A Few Good Men.”

That changed after the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001 and suddenly found itself capturing fighters that it did not want to recognize as prisoners of war.

“I think most people would agree that the Al Qaeda is a terrorist organization,” then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld told reporters on Jan. 22, 2002. “It’s not a country. And to give standing under a Geneva Convention to a terrorist organization that’s not a country is something that, I think, some of the lawyers, who did not drop out of law school, as I did… worry about as a precedent.”

Over the years, Gitmo would become a holding facility for prisoners captured around the world, and now that the Taliban have retaken Afghanistan, the prison has outlived its original reason for its existence.

The first 20 prisoners from Afghanistan arrived at the detention facility in January 2002. Then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said that Guantanamo Bay might be the “the least worst place” to hold detainees from the Global War on Terrorism. That temporary solution turned out to be permanent.

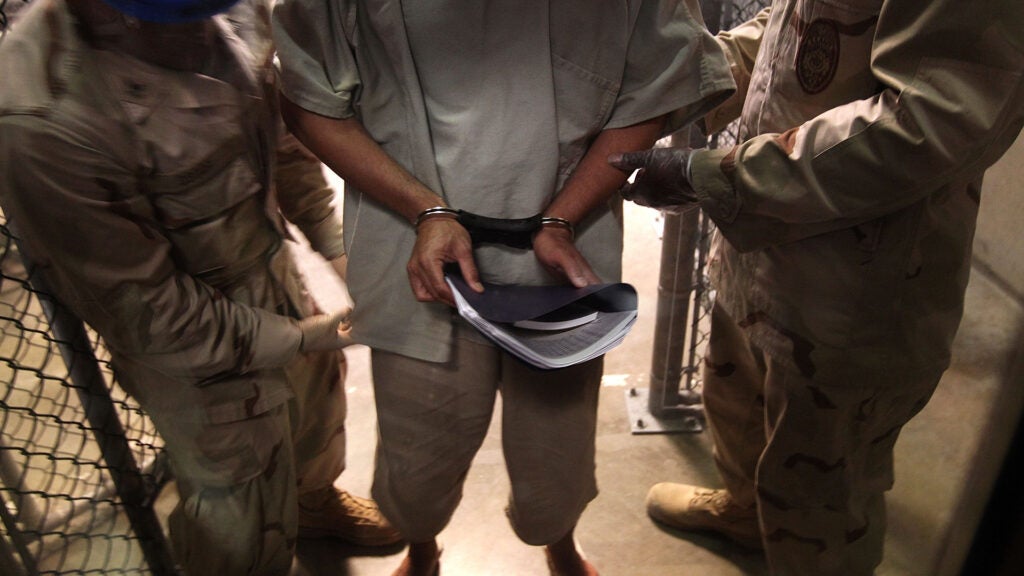

Close to 800 people have been held at the prison since it opened in 2002, but hundreds of those prisoners have been transferred to third countries since then.

Currently, 39 detainees are being held at Guantanamo Bay, said Army Lt. Col. César Santiago, a Pentagon spokesman.

One detainee, Abdul Latif Nasir, has been transferred to Morocco since Biden took office in January, Santiago said.

A total of eight detainees at Guantanamo Bay have been convicted using military commissions but only two men are still serving sentences at the prison, Santiago said. Two other detainees had their sentences overturned, one was paroled, and three have been transferred to other countries.

Santiago said the Defense Department is “fully supporting” efforts to close the detention facility and he referred further questions to the National Security Council, which is examining the issue.

Of the remaining detainees at Guantanamo Bay, 13 are eligible to be transferred to a third country, Santiago said. The U.S. government must reach an agreement with third countries before it can transfer detainees there, and that can be especially difficult with countries such as Yemen, which is wracked by war, according to NBC News.

Former President Barack Obama signed anexecutive order on Jan. 22, 2009 that called for the prison to be closed within a year, but those efforts were hamstrung by divisions within his administration and ran into intense resistance from Congress, which ultimately prohibited any of the detainees from being transferred to the United States.

The United States captured Guantanamo Bay in 1898 during the Spanish-American War. Since 1903, the U.S. government has leased 45 square miles of Guantanamo Bay for the naval station. That lease became permanent in 1934, and the U.S. military’s presence in Cuba has survived the 1959 communist revolution.

Because the detention center at Guantanamo Bay is located on Cuban sovereign territory, the prisoners held there were initially unable to challenge the legality of their detention. That changed when the Supreme Court ruled in 2008 that the detainees could file habeas corpus petitions.

Earlier this month, negotiators from the House of Representatives and the Senate reached an agreement on the latest defense policy bill, which extends the ban on transferring prisoners from Guantanamo to the United States through the end of 2022.

The ban on transferring detainees to the United States is simply a continuation of the status quo for the Guantanamo Bay detention facility, said Brian Finucane, a senior advisor with the International Crisis Group, an independent research and advocacy group that works to prevent wars and shape peace.

The more significant issue is that the Biden administration has not made closing the prison a priority, Finucane said.

“They’ve put it on the backburner,” Finucane said. “They don’t seem to have a plan for closing the facility. They don’t seem to have a plan for fixing the military commission mess.”

The Biden administration needs to figure out which detainees can be prosecuted in federal courts and which can be transferred to a third country, where they could end up being released, he said.

However, when then-Attorney General Eric Holder announced in November 2009 that accused Sept. 11 master planner Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and four other Guantanamo detainees would be tried in New York, the Justice Department ran smack into a political firestorm. The five men were ultimately referred to military commissions in April 2011, by which time then-New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg had objected to holding the trial in Lower Manhattan.

A decade later, the military’s proceedings against Mohammed are still ongoing.

“We are left today with the military commission process. It drags on, and the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks has still not faced a jury for his alleged actions,” Finucane said.

It is not clear how much progress the Biden administration has made toward shutting down the Guantanamo Bay detention center since Feb. 12, when Psaki told reporters the National Security Council would conduct a “robust” interagency review involving officials from the Defense, State, and Justice Departments to look into the matter.

That same day, Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said that Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin supports the Biden administration’s efforts to close the detention center.

“He fully expects to be a partner in the interagency process and discussing as that goes forward,” Kirby said during a Feb. 12 Pentagon news briefing.

Currently, 39 detainees are being held at Guantanamo Bay, of which 13 are eligible to be transferred to a third country, said Army Lt. Col. César Santiago, a Pentagon spokesman.

One detainee, Abdul Latif Nasir, has been transferred to Morocco since Biden took office in January, Santiago said.

Santiago said the Defense Department is “fully supporting” efforts to close the detention facility and he referred further questions to the National Security Council, which is examining the issue.

A National Security spokesman, who spoke on condition of anonymity under rules established by the White House, said the Biden administration is still focused on how to responsibly reduce the number of detainees held at Guantanamo Bay and eventually close the prison, but he did not provide any details as to how or when that would be done.

Yet Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), complained at a Tuesday hearing about closing the Guantanamo Bay detention facility that the Biden administration had not provided the Senate Judiciary Committee with any witnesses to talk about the plan for shutting the prison down.

“I’m not sure that there is a plan,” Grassley said. “Setting a goal – a policy goal – with no plan only invites disaster.”

At the moment, it seems as though the Biden administration lacks the will to work with lawmakers to tackle the problems associated with closing the prison, Finucane said.

“Gitmo is politically fraught and it is more of a political problem than it is a practical problem to solve,” Finucane said. “But there’s no sign at this point that the Biden administration is even interested in investing the political capital and try to solve it and try to convince members of Congress that: This is the way ahead; we have a plan of holding accountable the individuals allegedly responsible for 9/11; and here’s how we’re going to do it.”

More great stories on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.