Under dull yellow lights, dozens of paratroopers stood outside a building at the Green Ramp, a terminal area near the runway at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, grouped around a platform simulating the inside of an airplane.

In just a few hours they’d be jumping out of an aircraft into the inky blackness of night, not over Europe as the opening salvo in an invasion, but as part of standard airborne training in the 82nd Airborne Division.

Standing in a pre-jump training area called the mock doors, soldiers had their eyes fixed on a jumpmaster who was running through what sounded like a memorized script of instruction, similar to something you might hear after boarding a particularly intense roller coaster: If you have concerns about your equipment, ask someone. Wait for the green light. Listen to the jumpmaster. If there’s a fire on the aircraft, get away from the fire. And “do not pass the fucking seat” at the end of the row before it’s time for you to stand in the door.

Oh, and by the way, if you become a “towed jumper” — a malfunction resulting in a trooper literally being dragged behind the aircraft explained with the bang of the instructor’s fist against the fake airplane, simulating the sound of “you hitting up against the side of the aircraft” — do not interlock your fingers. If the soldier interlocks their fingers instead of overlapping their hands and is knocked unconscious from hitting the side of the airplane, the jumpmaster explained, it may not be immediately clear that they’re unconscious.

“Airborne?” he asked.

“Hooah,” the soldiers answered in unison.

“Hell yeah,” he said, before launching into the next piece of instruction during the Feb. 3 exercise briefing.

The paratroopers with the 82nd Airborne Division were preparing for a night jump operation, an exercise which had been planned months before the division got word that it would be deploying to Eastern Europe in the face of Russian aggression. Just hours before, soldiers with the 18th Airborne Corps had left for Germany.

While one group of soldiers was briefed by the jumpmaster, another group of soldiers were inside Pax Shed 1 — a staging area where the paratroopers wait beforehand and gear up when it’s time to go — sprawled on the floor and benches, shooting the shit and eating dinner. For more than a few, it appeared to be burgers and milkshakes from Cook Out, a local fast-food chain just outside the gate, or pizza. Jumpmasters in the crowd were easily identifiable by red hats or red patches on their uniform, with some sporting nicknames like ”Natty Light” and “Soft and Delicate.”

[embedded content]

As relaxed the soldiers appeared, they could have just as easily been waiting for a commercial flight home. But there is of course an inherent nervousness that comes with jumping out of airplanes, no matter how many times they’ve done it before.

A group of paratroopers with the 505th Infantry Regiment said they’d just jumped the week before, though that jump was “Hollywood” – meaning they wore only their uniforms and parachutes but no other equipment — while the one on Thursday was with their combat gear. The jump that night was also going to include dropping heavy equipment, a Humvee and artillery piece, to test the paratroopers’ abilities to get things up and running in the dark.

“I don’t think anybody is just like, not nervous about anything that’s going on,” one soldier said. “This is my 25th jump and I’m still nervous about it.”

“My mom does not like it,” another chimed in. “She’s seen a jump before … she thinks it’s cool but she gets scared every time I tell her about it.”

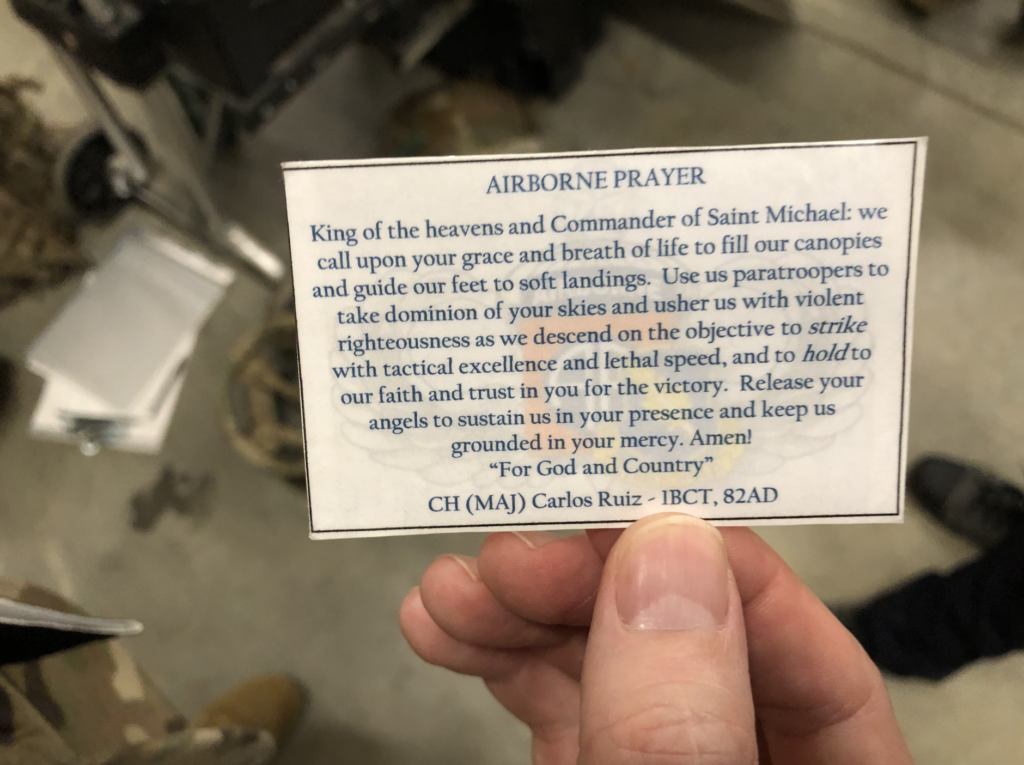

And almost everyone has their own pre-jump rituals, most of which appear to be praying for a safe jump. One soldier sitting nearby was reading a Bible. Another soldier said he prayed for “about 15 minutes straight.” The public affairs officer with 1st Brigade shared a card that he got from the chaplain, on which the Airborne Prayer is written. He keeps it with him on every jump.

Practice, however, is the best preparation. Staff Sgt. Thomas Gutierrez, one of the trainers, explained that before the jump when soldiers are running through the steps on the practice aircraft, including emergency procedures and red light exits. The red light by the door of the aircraft can come on for any number of reasons that “prohibits safe exits and descent all the way to the ground.”

“Could be anything,” said Gutierrez, who has jumped 95 times. “Could be that maybe the aircraft was going too fast, or a velociraptor in the drop zone. Who knows.”

Each step needs to be repeated countless times so that each soldier knows what to do, and has it ingrained as muscle memory. The goal is to make jumping out of a plane feel like second nature so that once soldiers are preparing to jump, their brain “kind of turns off” as they work through a checklist, Gutierrez said.

That’s particularly important with night jumps, which are more challenging for obvious reasons. It’s not just that it’s harder to see. It’s harder to see everything: Your equipment, the people around you. Even the ground.

Nevertheless, roughly an hour after the soldiers were seen eating and chatting, three C-17 Globemaster III aircraft loaded with soldiers were circling around the Holland Drop Zone. The cool breeze earlier in the day had picked up into chilly gusts of wind, casting doubt on whether or not the soldiers would actually be able to go through with the jump. But that didn’t stop the heavy equipment drop. Despite their size, the Humvee and artillery equipment floated almost gracefully to the ground, until they landed with a loud and rather graceless “clang!”

Less than a half hour later, the aircraft circled back. In what appeared from the ground to be perfect synchronization, paratroopers executed the jump one by one. As they quietly and slowly descended under a starry night sky, a faint exclamation of what sounded like “Fuck!” in the distance marked their landing. It was just another day in the double-A.

What’s hot on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.