Welcome to a That One Scene, a semi-regular series in which Task & Purpose writers wax nostalgic about that one scene from a beloved movie.

Hollywood has attempted, time and again with poor results, to portray what happens when an unidentified or unauthorized aircraft or missile threat penetrates friendly airspace. “Top Gun” and “War Games” tried, but wound up giving us classic 1980s cheeseball cinema. There is a noticeable absence of films that capture the pulse-pounding chess game of ground-controlled interception (GCI) – a sensation that is only amplified when lives are on the line.

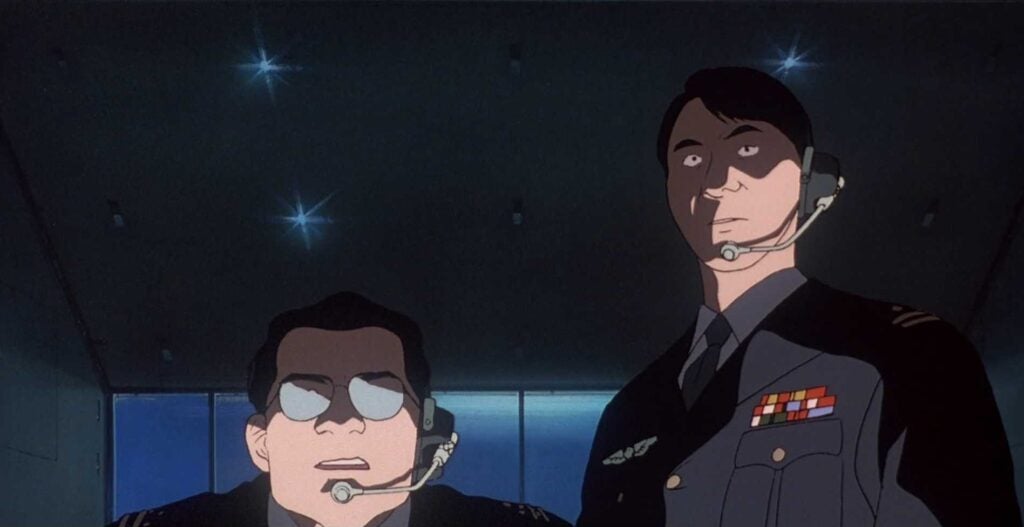

Enter “Patlabor 2: The Movie,” an obscure, contemplative anime film from Japanese director Mamouru Oshii of “Ghost In the Shell” fame. In between intricate artwork, a thrilling storyline about a plot to bring civil war to early 2000s Japan, and musings on the ethics of the application of military force, one scene stands out as the single most realistic portrayal of GCI ever put to film.

As tactical displays fill the screen and ominous music plays alongside frantic radio traffic, a scene unfolds that’s so technically dense and authentic, we at Task & Purpose had to consult several subject matter experts to make sure we understood exactly what was going on.

[embedded content]

The scene takes place in the winter of 2002 in Japan. A rogue F-16J aircraft fires a TV-guided missile — meaning a missile that uses a camera feed for steering — at the Tokyo Bay Bridge, destroying the middle section and throwing Japan into a state of fear not experienced since Curtis LeMay’s strategic bombing of the mainland during World War II.

Only days later, Fuchu Central Strategic Operations Center (SOC) detects a sortie of three more F-16Js, call sign “Wyvern,” this time armed with bombs, on a direct flight from Misawa Air Base to the heart of Tokyo. With only minutes to spare, and suspecting another attack, four F-15 STOL/MTDs — a highly maneuverable F-15 prototype — are scrambled to intercept on two separate paths in the hopes that one of the aircraft will make contact with the incoming bogies.

Fuchu officials guide the F-15s, call signs “Wizard” and “Priest,” to the incoming F-16Js. The F-15s attempt to make contact, but Wizard cannot see Wyvern or pick them up on radar, despite being nearly on top of them.

Wizard disappears in a flurry of radio interference, before transmitting via their transponder that they’d been shot down. Wyvern then pivots into a direct trajectory towards Tokyo central, dropping altitude and accelerating, as if making an attack run, and Priest is given clearance from Fuchu SOC to fire as soon as they make radar contact. In addition, Fuchu SOC alerts the Iruma Air Defense Artillery batteries to prepare to engage, now fully anticipating an airborne attack. Civilian air traffic controllers at Narita International Airport scramble to ensure that the incoming aircraft don’t harm passenger planes in holding patterns, further driving home the dire implications of this incursion.

Just as Priest prepares to fire, the interference clears, and the targeted aircraft reveal themselves to be Wizard flight, frantically asking for orders. Fuchu SOC immediately calls off the attack, bewildered that the airborne threat has suddenly disappeared, and recalls the interceptors back to base.

The entire attack was an elaborate ruse, a hack of the Fuchu SOC radar systems and jamming of their radio communications, in an attempt to cause the responding aircraft to engage each other. At the very least, the digital assailant showed the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force that they had the capability to infiltrate their systems and wreak havoc, sowing further doubt and terror among the ranks.

This scene is extremely dense, so we’re going to do a breakdown of exactly what the filmmakers got right, because the detail is as close to real life as it gets (despite the film being a cartoon). High-octane aerial combat movies like “Top Gun” and “Behind Enemy Lines” do not hold a candle to the precision and attention to detail we see in this film, not to mention the chest-thumping thrill ride of the action as it plays out.

When I interviewed our subject matter expert, a former Navy strike force analyst, he had this to say: “All of the brevity terms are used properly, nothing feels out of place like the typical Hollywood screenwriter trying to sound like the military by using terms they found on Google like a lot of films and shows. The Ground Control Intercept (GCI) depiction is exactly how that would play out (TREBOR vectors PRIEST and WIZARD into the target; the fighters are very reliant on the controllers view of the battlespace with only targeting capabilities with their radar). The radar screens aren’t the spinning ‘sonar blip’ bullshit you get in a lot of games, movies, and animation. It’s very true to the displays you actually see in a control tower, with the IFF/squawk codes identifying each aircraft or flight.”

So, with that in mind, let’s dive deeper into that one scene.

The technology

The film uses period-accurate monochrome radar displays that refresh only when the radar beam makes another circuit. Tracked air assets are marked with their “squawk codes,” rather than plane names.

The choice of aircraft is another authentic touch. The F-15 STOL/MTD, was an F-15 variant designed in the 1980s to test the concept of thrust vectoring and super-mobility, and is one that few people aside from those who read Jane’s Fighting Planes books would have known about in 1993.

The radios are harsh, muffled, and staticky, and the pilots’ breathing interrupts their dialogue, which is a very real thing. The pilots have to be guided onto their targets due to the fact that features like sensor data sharing between aircraft were only in their infancy at the time of the film’s release, meaning the pilots had to manually steer their narrow-view onboard radar onto the target by taking verbal directions from the SOC, whose more powerful 360-degree radar was much better equipped for locating the general position of targets.

The dialogue

While most movies get radio traffic wrong with amateurish phrases like “over and out” or “I repeat,” Patlabor characters not only use believable dialogue during radio transmissions, but also speak in heavily accented English.

This is a huge detail that most aviation films neglect, even ones that depict NATO allies, which often simply feature the pilots speaking their native language despite the fact that English is the universal language of air traffic communication. The pilots and air traffic controllers speak in measured, subdued tones, suggesting a high level of training and preparedness. Even the air battle manager and director speak to each other in a manner that, while grim, is still calm and businesslike, underscoring the fact that while the situation is quite precarious, shots have not yet been fired. This is contrasted with the excited, terrified shouts of the civilian air traffic controllers at Narita International Airport, which add to the tension of the scene.

The pilots and controllers give their headings in degrees magnetic, saying the numbers individually like “one-niner-zero” instead of “one-ninety,” and provide their altitude in angels (thousands of feet) which adds another layer of credibility. The terms used, such as “no joy” (no visual contact) “bogey dope” (request target heading, altitude, and airspeed) and “say again” as opposed to “repeat,” are spot on, preventing a good deal of cringe from those in the know.

Tactics, techniques, and procedures

Contrast this scene with the hyped-up, Aqua Net-and-cocaine pacing of the air combat scenes of classics like “Top Gun,” and you’ll immediately see that this is a more measured, authentic approach to how air operations work. For starters, one of the biggest things that military aviation movies often neglect is that the airborne radars of fighter aircraft are very limited, only sweeping in a narrow ray in front of the aircraft to avoid microwaving the pilots and crew. It stands to reason that Wizard and Priest flights would be heavily dependent on the Fuchu Central SOC for guidance as to the general vicinity of the intruders, and the scene illustrates this beautifully.

The incoming aircraft are identified, radio hails are sent up, and when there’s no response, interceptors are launched. Once the aircraft checks in, the air traffic controllers give guidance, and the initial intercept time is revised while the pilots begin to search for the target visually and with their onboard targeting radar. The coordination is continuous, with Fuchu Central SOC feeding Wizard and Priest targeting data while trying to deconflict the situation on the ground, to no avail. When Wizard gets “shot down,” the squawk code “7700,” — the international code for “mayday,” or an airborne emergency – appears onscreen at their last known position.

The depiction of a cyber attack

Cyberspace is an ever-growing domain of warfare on the modern battlefield, and concerns about its role in a conflict with a near-peer adversary are becoming more commonplace. This scene presents three forms of electronic warfare: GPS spoofing, hacking, and signal jamming. The culmination of this multi-pronged cyber attack is when two friendly aircraft come within seconds of firing on one another.

In the film, this is done to try to incite a civil war, but in real life, GPS spoofing has become so common that hackers sell kits for $300 to allow the user to send false GPS data. Iran has already made dubious claims that they have mounted GPS spoofing attacks on U.S. air assets. The scene demonstrates this when Wizard says “We had heavy jamming and now lost position,” indicating that their communications and their GPS systems were being tampered with. The producers of this film weren’t in possession of any classified information either, since GPS spoofing and jamming was something that even the Iraqis used during Operation Desert Storm in the hopes of defeating GPS-guided bombs aimed at Saddam’s palace.

Hacking is another daily reality in the modern world, and cyber attacks against various governments are now common shows of force. While it’s not officially known whether or not any tactical systems have been hacked, as revealed in this scene, the possibility of this happening is still greater than zero. Signal jamming, however, is one of the oldest electronic warfare tricks in the book, and involves flooding entire swaths of frequencies with signal noise, which not only forces the enemy to limit communications, but also makes decryption easier by reducing the number of usable frequencies to a select few. This scene accurately portrays electronic warfare when the adversary coordinates Wizard getting “shot down” on the hacked radar display with heavy signal jamming that prevents Fuchu SOC from making contact with them via radio or transponder, adding to the illusion of Wizard being killed, and preventing Priest from deconflicting the airspace once they make radar contact with what they think is the intruding Wyvern flight.

Overall, myself and our subject matter expert both agree that this scene is the most authentic portrayal of air operations ever put to film. Additionally, I interviewed several former military air traffic controllers, strike analysts, and aviators, and their opinion was unanimous: This is pretty dang good. It totally abstains from excessive showmanship, replacing spectacle with the terrifying feeling that something like this could really happen. It’s an outstanding example of how technical detail and thorough authenticity can turn a minor scene, whose only function is to move the storyline forward, into seven minutes of nail-biting suspense.

The opinions contained in this article are solely those of the author and the persons interviewed and do not represent the opinions of the Department of Defense or the United States Government

What’s new on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.