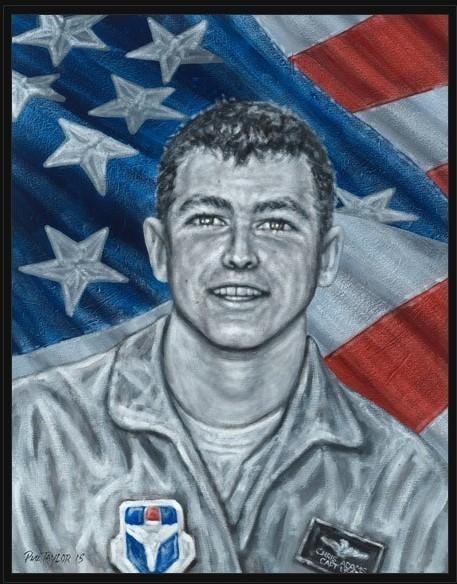

When 800 mourners gathered for the funeral of Air Force Capt. Christopher Adams on Long Island, New York in July 1996, few could hold back their tears.

“Even the bugler wavered for a moment in playing ‘Taps,’” The New York Times reported in its article about the funeral, and for good reason. The 30-year-old Adams was beloved by his community and by his fellow airmen, one of whom he gave his life to save in the moments before a deadly terrorist attack in Saudi Arabia.

Now, 26 years later, Adams has been recognized for his sacrifice by his former unit, the 71st Rescue Squadron, which awarded him a posthumous Airman’s Medal at a ceremony on Friday at Moody Air Force Base, Georgia.

“Within Air Force Rescue we have a motto, ‘These things we do so that others may live,’” said the squadron commander, Lt. Col. Brian Desautels, in an Air Force press release. “Chris lived that motto on the last day of his life, saving a fellow airman to make sure he was able to come home.”

The attack on June 25, 1996, which killed 19 airmen and wounded hundreds more, was months in the making. Seven months earlier, a car bomb detonated at Saudi Arabian military offices in Riyadh, the nation’s capitol, prompting leaders at King Abdul Aziz Air Base to fortify American installations against similar threats. About 3,000 airmen, several hundred Army soldiers and some British and French troops lived in the nearby Khobar Towers complex, which had concrete Jersey barriers placed along the perimeter fence and the security presence beefed up at the complex gate, according to a 1998 article by Air Force Magazine.

“We’ve turned our living area into a bit of a fortress-with cement barriers and concertina wire,” wrote the commander of the Dhahran-based 4404th Wing, Brig. Gen. Terryl Schwalier, in a letter to his wife, according to Air Force Magazine. “Our cops are on 12-hour shifts-having doubled up on the gates and increased their patrols.”

But the complex still had a weak spot: a stretch of fence along the northern perimeter about 80 feet away from buildings 131 and 133. Beyond that fence was a parking lot where Saudi Arabian families often stopped so they could visit the nearby city park. Despite newly-installed Jersey barriers, sentries on the rooftops of 131 and 133, and routine Saudi police patrols through the parking lot, it was still a vulnerability where attackers could potentially threaten the hundreds of service members living in the buildings across the fence.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment and gear in your inbox daily.

June 25 was supposed to be Schwalier’s last day of command. By 9:00 p.m., many Khobar Towers residents were in their rooms, and the final Muslim prayer call of the day was just ending. Staff Sgt. Alfredo Guerrero, a security forces airman (the Air Force equivalent of military police) went to the top of building 131 to check in with the two sentries there. From the roof, the three airmen watched a sewage tanker truck and a white car drive into the parking lot across the northern perimeter fence. The truck backed up toward the fence line, stopping right in front of the center of the north side of 131, at which point the driver and a passenger leaped out of the truck and into the white car, which raced out of the parking lot.

Clearly, this was a threat, prompting the three airmen to raise the alarm from the rooftop. Residents began spreading the word to evacuate from the top floor down, while on the ground a roving security forces car waved people away from Building 131. HC-130 Hercules pilot Capt. Christopher Adams, however, was not deterred. Instead of evacuating 131, Adams rushed to warn his boss, Lt. Col Thomas Shafer, the commander of the 71st Rescue Squadron at the time.

“When he came into my room, Chris saved my life,” Shafer recalled in the Air Force press release.

Then the bomb went off. The sewage truck exploded with the force of 20,000 to 30,000 pounds of TNT, according to Air Force Magazine. It launched chunks of the Jersey barriers into the first four floors of building 131; blasted the walls off the building’s north, east and west sides, and sheered the facade off the top three floors.

“I was a few feet into the center alcove between rooms when the bombs went off,” Shafer recalled. “I don’t think I lost consciousness, but I remember becoming aware that I was screaming.”

The mere moments of warning Adams gave Shafer had saved his life, the lieutenant colonel said in his recommendation for Adams to receive the Airman’s Medal.

“As a result of Captain Adams’ swift actions, Lieutenant Colonel Shafer survived with minor injuries,” Shafer wrote. “His personal courage and decisive action undoubtedly saved the life of his fellow wingman.”

Adams was not so lucky: he was killed in the blast, along with 18 other airmen.

The Airman’s Medal is awarded to individuals who distinguish themselves “by a heroic act, usually at the voluntary risk of his or her life but not involving actual combat,” according to the Air Force. And though Adams’ final act was a heroic one, it was far from his first. At his funeral in Long Island, friends and family remembered him as a “tremendous person” who, at the age of 10, took on the role of a surrogate father for his seven brothers and sisters when their actual father passed away.

“You’re always a hero to me; I love you,” one of his brothers, Billy, had written in a poem about Adams, according to the New York Times.

It makes sense that a guy like that would find a home in the 71st Rescue Squadron, whose whole purpose is to put themselves at risk to save others.

“Adams represents what many of our airmen prepare to do,” said Desautels, the squadron’s current commander. “I’m just glad we were able to get him the recognition he deserved.”

What’s new on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.