The U.S. military footprint in Europe has exploded in the two months since Russia invaded Ukraine, with more than 100,000 troops now on the ground on a continent where the talk until recently had been on how and where to cut back.

The looming question for Pentagon planners now is how many of those troops should stay, and for how long.

Russia’s assault on Ukraine has sparked a high-stakes debate about how best to use American boots on the ground in Europe as both a show of solidarity with Kyiv and as a deterrent against any potential Russian move against NATO’s eastern flank, such as an attack on Baltic nations or a strike on Poland. Inside the Pentagon and in national security circles across Washington, the questions center on whether the U.S. should dramatically increase the number of troops permanently stationed across Europe — with all the attendant costs and commitments — or instead ramp up so-called rotational deployments, which see service members cycle through shorter-term missions typically lasting under a year.

Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark A. Milley recently told Congress he favors the construction of new permanent U.S. bases in eastern Europe but wants to staff those facilities primarily with rotational troops. Such an approach carries a host of benefits, most notably on the financial front. Rotational deployments traditionally have been cheaper, mainly because the troops’ spouses and children usually remain at home in the U.S. rather than move overseas for a multi-year stay on an American military base in Germany, for example.

But that approach has more than its fair share of critics, especially given today’s critical security climate in Europe.

Proponents of more permanent deployments say that simply increasing the number of U.S. troops on rotation through Europe isn’t a strong enough show of force to truly change Russian President Vladimir Putin’s cost-benefit analysis. And they argue that a more permanent American presence would carry tangible benefits in the worst-case scenario of an all-out Russia vs. NATO showdown.

SEE ALSO: Russian pilot seen in China jet trainer crash

“We can’t have forces in garrisons. We need to have them on the front lines. They need to be ready,” said Jim Townsend, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for European and NATO policy during the Obama administration.

“We’ve got to lean toward deployed forces in Europe. There’s a role for rotational forces, but rotational forces are vulnerable when they rotate,” he told The Washington Times. “We need to have full-time forces there. I know the Pentagon doesn’t like to hear that for various reasons, but I think it’s a mistake to just do more of what we’re already doing. We’ve got to have armor that is there.”

“You have to load up a ship [when rotating], and if you’re actually fighting the Russians, you’re in a pitched battle with them, those ships may or may not make it. I’d rather have them on the continent. It brings strength to deterrence,” he said.

The push to reimagine America’s approach to troop deployments comes against the backdrop of Europe’s biggest ground war since World War II — and the Pentagon’s longer-term strategic hopes of reorienting U.S. power to face China, not Russia. Russia’s unprovoked assault on Ukraine continued Monday with strikes on Ukrainian rail and fuel depots, as the Russian military looks to cripple Ukrainian supply lines and prevent equipment from reaching the eastern front.

Russian forces have massed in eastern Ukraine in a major offensive on the disputed Donbas region, which has become the epicenter of the war. Russian troops also are seeking to capture the devastated port city of Mariupol, which would allow Moscow to create a land bridge between the Donbas and the Crimean peninsula, which Russia forcibly annexed in 2014.

To help beat back that Russian offensive, U.S. Secretary Antony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin visited Kyiv over the weekend and announced a new American military assistance package to Ukraine. Underscoring the high stakes of the current conflict, Ukrainian officials said such aid is crucial but that the Western world must do more to stop Russian aggression, which they said will surely not stop in Ukraine.

“As long as Russian soldiers put a foot on Ukrainian soil, nothing is enough,” Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba told the Associated Press on Monday, adding that the U.S. and NATO must do more to “stop Putin in Ukraine and not to allow him to go further, deeper into Europe.”

Russia for its part was complaining about the growing number of U.S. troops near its borders weeks before Mr. Putin authorized the invasion of Ukraine Feb. 24. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov in early February complained that it was the U.S. that was fueling tensions in the region by sending more troops to Poland and Romania in response to the Russian military build-up on the Ukrainian border.

“Clearly, Russian concerns are justified and understandable,” Mr. Peskov told reporters Feb. 3 at a briefing. “All measures to ensure Russia’s security and interests are also understandable.”

Ironically in light of the current debate, the Biden administration at the time defended the troop deployments in part because they were only temporary and could be reversed if Russia stepped back as well.

“These are not permanent moves — they are precisely in response to the current security environment in light of this increasing threatening behavior by the Russian Federation,” department spokesman Ned Price said.

A major build-up

The Biden administration has vowed to defend every inch of NATO territory from Russia, essentially guaranteeing a world-war scenario if Russian troops press beyond Ukraine. A central part of the U.S. deterrence strategy has been to send tens of thousands of additional troops to Europe at a pace not seen since the Cold War.

Such major increases in American troop deployments would have seemed unthinkable just a few years ago. Former President Trump and his national security team, skeptical of many U.S. NATO allies, looked to shrink the overall number of U.S. troops in Europe and to reposition more than 10,000 forces from Germany to other locations on the continent.

President Biden and Mr. Austin quickly stopped that plan after taking office in January 2021.

Fifteen months later, America’s footprint has ballooned to its highest level in years. In January, as the world watched to see if Mr. Putin would attack Ukraine, there were about 80,000 U.S. troops stationed across Europe.

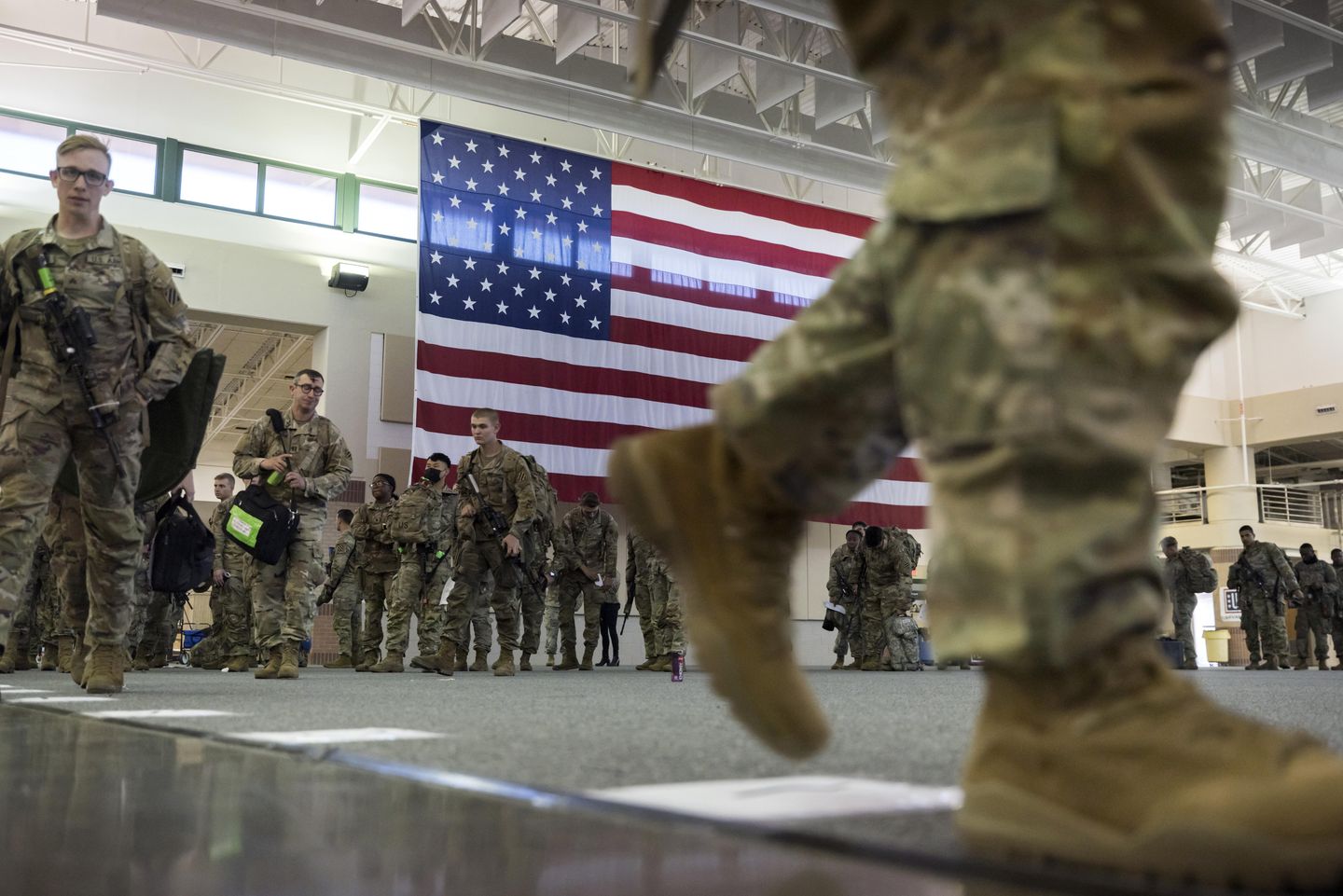

Now, there are 102,000 American forces in Europe, U.S. military officials told The Times on Monday. Of those, about 65,000 are on a permanent deployment, meaning they’ll remain there for several years. The remaining troops are in Europe on a rotational basis, officials said.

Such an approach has become common, both in Europe and in other theaters with a major U.S. troop presence, including the Korean peninsula. Troops often arrive on a short-term deployment to take part in a series of major military exercises, or they could be sent to a hot spot — such as eastern Europe — temporarily as a way to demonstrate American resolve in the face of a potential enemy attack.

In eastern Europe in particular, Gen. Milley believes the U.S. can essentially have the best of both worlds.

“My advice would be to create permanent bases, but don’t permanently station. So you get the effect of permanence by rotational forces cycling through permanent bases,” Gen. Milley told House lawmakers during a recent hearing. “And what you don’t have to do is incur the cost of family moves, PXs, schools, housing, and that sort of thing. So you cycle through expeditionary forces through forward deployed permanent bases.”

“You get the effect of permanent presence of forces, but the actual individual soldier, sailor, airman and Marine is not permanently stationed there for two or three years,” he said.

That approach clearly has its supporters inside the Pentagon. But there are strong arguments to be made for more permanent deployments, and there’s some evidence that rotations don’t always generate as much cost savings as anticipated.

Perhaps more importantly, permanent troop deployments may send a stronger signal to both allies and enemies. Poland during the Trump administration actively lobbied for more American troops on its soil and even offered to build a $2 billion “Fort Trump” to house them.

“In terms of diplomatic or political-military factors, forward stationing is preferred by American allies overseas over rotational deployments. Allies perceive forward-stationed forces as a sign of a stronger, more enduring commitment from the United States,” U.S. Army War College researcher John R. Deni said in a 2017 report examining Army deployments around the world.