The following essay was written by Joseph Simboli Jr., one of the members of the 89th Infantry Division who liberated Ohrdruf, the first Nazi concentration camp to be discovered by American forces in April 1945. For decades, Simboli struggled with the internal turmoil of what he saw and couldn’t prevent on that sunny April morning in 1945, according to his family.

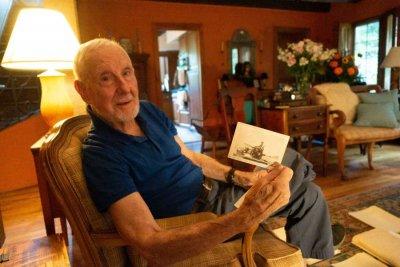

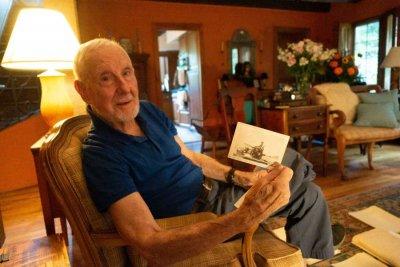

Simboli never shared his wartime story in detail, until he lost his wife Geraldine at age 84 in 2019. The day after her funeral, Simboli pulled out decades of personal writings and artifacts from WWII.

Before Simboli died in May of 2021, his family asked if he would like to see his work published. He smiled and waved his hand, his family said. “No one would want to read my musings,” he said. “Well, unless you think so. Then, please!”

April 4, 1945.

It was a beautiful, sunny morning in Ohrdruf, Germany, and my unit, the 89th Infantry Division, was on patrol. We had just moved south to investigate conflicting reports that a Nazi concentration camp existed nearby. Rumors of such camps had circulated, but we had found none. German fighter planes had been strafing overhead—no doubt a last-ditch attempt to keep their genocide secret from the world.

We had stayed in our covered positions, biding time until the attack ended. The deluge of mortar no longer made my legs vibrate uncontrollably, the way they did the initial many times a shell burst inches from my body. When the thunder ceased and the clouds of smoke cleared, and we resumed our movements deeper into the country, my legs buckled again. This time it wasn’t because of mortar. It was from the waves of the most putrid smell I could never possibly imagine.

Rotting flesh, burned feces, stale urine, and dirty laundry all conspired to burn my nostrils and throat like an inferno. My stomach felt as though I was on an elevator that couldn’t find its desired floor. It took everything I could do not to throw up.

Then again, maybe the reason I didn’t throw up was because, as we approached the unimpressive-looking camp, and then crossed through the surrounding 15-foot-high wire fence into its grounds, I struggled to feel anything at all. My mind had frozen: I simply couldn’t process what I was seeing.

Bloodied and wet, half-naked, and emaciated bodies, some still warm, in tattered striped clothing, frozen in unnatural positions, were piled haphazardly on the ground in what appeared to be the main assembly area of a camp. Whether they were men or women wasn’t clear. The hand of an older individual with a gaping head wound fought its way through the mound to be seen. Railroad ties, like a makeshift pyre, were strewn with hastily half-burned and decomposing victims. There were more skeletal dead bodies buried in common pits, with hands, torsos, limbs all sticking out.

I don’t know that you can know a life-changing moment when it’s happening. It seems as if it would be impossible, because most kinds of impactful moments have some level of disbelief—or else because overwhelming feelings, like sheer horror and revulsion, don’t allow your mind to process everything that’s happening. I know the profundity of what I saw in Ohrdruf that morning was completely lost on me right then, and, in truth, in the days and weeks, even months, that followed. None of us there had any prior idea of the atrocities being inflicted. We had no reliable reports; no photos or videos had been splashed all over the media to document it, as we have today. No history books had laid them out in photographic accounts, as my children and their children have now seen. We trudged through an unknown, unexperienced evil—unaware, with every step, how that evil took hold in us and shaped our attitude, beliefs, and future actions.

A week after we found the camp, people still vomited at the sight and stench of the “beating shed,” as prisoners later said that small building was called: 115 strokes as punishment with a sharp-bladed shovel for a minor infraction. Gen. George Patton was among those throwing up when he visited with President Dwight Eisenhower and other generals soon after we arrived. We learned much from the surviving prisoners about Ohrdruf and the terror that had occurred in the days leading up to our arrival.

Ohrdruf was a forced labor camp and a subcamp of Buchenwald, which would later be recognized as one of the largest Nazi concentration camps. At one time, Ohrdruf had around 12,000 prisoners, but when news of our approach came in late spring of 1945, the Nazis began a systematic evacuation of the camp—as barbarically systematic as the slaughter in camps themselves.

A few days before our arrival, nearly 10,000 prisoners were marched to Buchenwald, 30-something miles from Ohrdruf—I should say those who were capable of walking. The SS guards machine-gunned those too ill or disabled to make the trip. Some prisoners escaped along the way, hiding in the woods for days, only to reappear at the camp after we arrived. Others were gunned down during the march. The SS guards must have been told to “cover up” their atrocities, hence the lye on the bodies in the beating shed and the makeshift pyre of railroad ties with heaps of half-burned bodies. Apparently, prisoners had been forced to exhume decomposing bodies and cremate them.

But the SS guards gave up the effort and left the grisly remains for all to see.

Gen. Patton commanded the burgermeister—similar to a town mayor—his wife, and the surrounding townsfolk to come to Ohrdruf to see what their fellow countrymen had done to their other innocent countrymen, and to dig graves for the dead. The idea that these and other townspeople might have prevented the mass slaughter by not turning a blind eye to what, by most accounts, was whispered throughout the countryside, left a burning fury inside me for decades. We learned the burgermeister and his wife killed themselves that night, a small justice.

Looking back, I’m not sure if something died in me that night as well, or if something new was born. I was numb after Ohrdruf. We all were. It’s hard to figure something like that out, especially when you can’t feel much at all.

Then again, we didn’t have much time to consider it. After Ohrdruf, we expected to head to Japan. But with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the country’s formal surrender to the Allies, our unit and others were rotated to the French coast, awaiting ships to be transported back to the United States. The thought of home was surreal. Going back to “normal life” was what so many of us talked about for so long, and yet after everything we experienced, how do you ever just “go back”?

When I joined the service, I was just a 20-year-old boy from Pennsylvania who had been wide-eyed about life, looking for adventure, caught up in the swell of patriotism of the war raging in Europe and Japan. I had spent a year dodging bullets and bombs, detonating mines, and setting up booby traps, roadblocks, and pillboxes. I’d lost my best friend on the first day of combat and hundreds more in one night while crossing the Rhine River during Operation Varsity. I’d hidden in cellars along the Moselle River bank and listened to church bells toll as our battalion climbed into small, unreliable boats, paddling for our lives as the sky lit up with fire.

I saw everything that war does to people: fear, rage, guilt, barbarism. By the grace of God, I made it through, for the most part physically unscathed. But what I encountered that first day at Ohrdruf, I still, at 94 years old, can’t wrap my head around; it caused an invisible wound unlike anything I’ve known, one that I struggle to put words to even now.

We didn’t go home as planned, at least not then. Our company was diverted back to Ohrdruf. Back to that hellscape? The thought brought back the queasiness, which was made worse when we arrived: The stench was still there, months later. Memories of those heaps of bodies and body parts, the beating shed, the brass knuckles, the indignity of it all and utter disregard for human life came flooding back, as did the burning inside.

Our mission this time was to rebuild the fence around the camp that had been destroyed by an attack. As we began, groups of German women, who had worked in the concentration camps for the Nazis, were brought in to be held. Looking back through the journals I kept of the war after I returned home, I see that I described these women as “unusually tough.” In hindsight, that was a very polite way to describe what these individuals were. As we worked to rebuild the fence, they lobbed the most despicable verbal assaults at us with the force their male compatriots did earlier from the skies. Profanity—I won’t recall it here—unlike anything I’d heard.

They taunted us, ruining our work, undermining our efforts, even throwing pieces of the poles we had just trimmed and cleaned up, back over the fence. There was no remorse for what the Nazis had done and what these women oversaw the Nazis do and facilitated their being able to do, no humility in their country’s fall from power and respect on the world stage. As far as I could see, there was not a stitch of humanity left in them. Again, that burning inside took hold. I wanted to strike out at them, silence their vile spewing, make them pay, hold their hands to the pyre of accountability, not just for their petty insults thrown at us, but for the holocaust they and others wrought.

It’s an animalistic urge that makes you want to take this kind of action, and as a man, especially, to take it against women. It certainly went against all my beliefs and codes of honor. A bunch of us griped repeatedly to our officers to be allowed to do something, but we were shut down and told not to react. But for the previous year, all we had done was “react” against the enemy—that’s what we were trained to do. And now, even with the enemy in our sight, still “threatening” us, with full knowledge of the worst that they had done, we still couldn’t do anything but swallow our anger, disgust, and contempt and continue reconstructing their pen.

I will never comprehend the manifestations of the Holocaust. And the memories of Ohrdruf’s liberation have never gone away; in fact, they are the ones that have remained with me most clearly and intensely and, as I’ve come to see, shaped many of my most ardent beliefs and actions. The nightmares have lessened and faded, but the existential nausea that I felt that first day has returned over and over, sparked by sights, sounds, smells, and events. These memories have been, and will always be, with me, like the spiked brass knuckles I found that they used in the beating shed.

I mentioned that I wasn’t sure if something died in me during my time at Ohrdruf, or if something new was born. After I got home, back to Pennsylvania, and tried to create a new “normal” life (I married an amazing woman, had five children, and worked as an artist and craftsman alongside my wife), I realized that it was both. My innocence died with the Nazis’ slaughter of the innocent lives I saw in the camp, and the millions of other innocent lives slaughtered in the Holocaust. They couldn’t prevent it from happening, nor could they do anything to help themselves when it was happening.

And I couldn’t have prevented it from happening. That raw, burning outrage that I had swallowed in Ohrdruf could either consume me or help me and others to live.

When faced with the impossible or the unthinkable, you have two choices: You can lose faith—in yourself, others, life, and God—or you can turn to faith to find meaning and purpose. There have been times when I’ve felt the former taking over. But when I got home from the war, I made a vow to myself that if ever I saw anything like this again, the widespread defilement of human dignity and life, I would have to do something about it.

I couldn’t prevent the horrific mass slaughter by the Nazis, but my memories of it and that burning outrage I still feel about it could serve as an inspiration to protect life, in all its various forms, especially the innocent. This is what I’ve done, whether that is in my art or community and political advocacy, along with my wife, for the last seven and a half decades.

A small honor to the lives that were lost. A great reminder to everyone that life is always worth living.

Joseph Simboli, 1925-2021, enlisted in the U.S. Army at age 17, and then served in World War II with the 89th Infantry Division. He attended and taught at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art, and then established, with his wife Gerry, their art studio, Simboli Design. He also enjoyed running and racing sports cars.

© Copyright 2022 The War Horse. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.