Read the original article on Business Insider

On August 1, 1943, U.S. Army Air Force B-24 Liberators took off from bases in Libya for an audacious raid on one of the Nazi military’s most valuable resources.

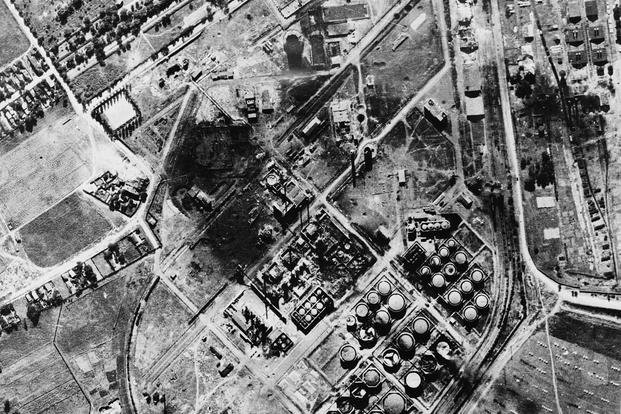

Operation Tidal Wave was meant to destroy Nazi-controlled oil fields and refineries at Ploie?ti, north of Bucharest, Romania. The campaign was unprecedented in scale, with 1,725 airmen taking off in 177 bombers.

The attack on Ploie?ti, a sweeping, low-level bombing raid, took a heavy toll on the U.S. airmen involved: 225 of them were killed, earning the day the grim nickname Black Sunday.

Many of those fallen airmen were not immediately recovered or identified.

Three-quarters of a century later, the U.S. Department of Defense’s POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) has been using archival research and modern forensics — including DNA analysis from exhumed skeletal remains — to account for airmen still missing from the 1943 mission.

The “Ploie?ti Unknowns Project,” which began in 2017, has so far identified remains of 19 Tidal Wave airmen and notified their descendants.

In the last three months alone, the Pentagon has announced the identification of five Ploie?ti airmen: Sgt. Elvin L. Phillips, 23; 1st Lt. Louis V. Girard, 20; Lt. Col. Addison E Baker, 36; 2nd Lt. David M. Lewis, 20; and Staff Sgt. William O. Wood, 25.

The mission

Operation Tidal Wave was the Allies’ first large-scale, low-altitude raid against a well-defended Axis target, and the stakes were high.

The oil fields and refineries spread across the 18-square-mile complex produced one-third of the Reich’s oil, which powered everything from cars and tanks to planes and warships.

Allied leaders who had agreed on the next phase of the war at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 believed that obliterating “Hitler’s gas station” would be critical to slowing the movement of Axis troops and supplies. They also knew such a mission would be costly.

Training for Operation Tidal Wave took place in Libya, where airmen from five different bomb groups lived mainly in tents in the sweltering desert around Benghazi.

Crews simulated bombing runs on a life-size replica of the refinery complex. Models of their assigned targets were built with wood and canvas. The airmen learned how to make use of the B-24’s relatively long range and heavy payloads for the 2,000-mile flight to Romania and back.

Despite the preparation, a variety of conditions made an already treacherous mission even more dangerous.

The airmen would be tight on fuel, flying lower and longer than usual, and dealing with maintenance issues caused by the harsh desert conditions, like sand clogging their engines.

The commander of the 44th Bomb Group warned his airmen that only half of them were likely to survive. Radio operator Norm Kiefer remembers a briefing officer saying “the target was so important that if we lost all of the attacking force but destroyed the refineries, it would be worth it.”

The message to airmen was that this single raid could shorten the war by as much as six months.

Early on August 1, crews began taking off from Libya, flying in formation across the Mediterranean toward their targets. Waves of B-24s followed each other, keeping radio silence to evade German radar.

Yet little went as planned on the path to Ploie?ti. Navigation issues led entire squadrons off course. Meanwhile, the Germans knew more about the raid, and were better prepared for it, than the Allies anticipated.

The airmen encountered heavy German resistance, including barrage balloons. The Germans also set smoke pots ablaze in the bombers’ path to obscure targets and blind Allied pilots.

Billowing clouds of black smoke limited visibility and interfered with navigation as the B-24s descended to drop their bombs. They flew so low — just 50 feet off the ground — that gunners on the bombers had to aim up at anti-aircraft guns on the roofs of buildings.

Other disguised defenses — anti-aircraft guns hidden among train tracks, oil tanks, and surrounding fields — greeted the vulnerable bombers as they streaked toward their targets.

The costs and recovery efforts

Operation Tidal Wave proved that the USAAF could carry out large-scale offensive bombing raids, but the feat came at a high price.

The raid knocked about 46% of Ploesti’s annual production offline, but the Germans had the refineries up and running at full capacity within three months. The U.S. Army Air Forces never tried another low-level raid against the Germans.

More than 50 of the 177 bombers involved did not return. German soldiers in the region captured 32 airmen alive and collected the remains of some who had been killed. Crashed bombers and bodies left a horrifying scene around Ploie?ti.

Because the bombers flew in waves and had separate targets, and because in many cases they missed their targets or purposely veered off-course after being hit, Allied forces struggled to recover the scattered, often badly burned bodies.

“They crashed all over the place,” said Christine Cohn, the lead DPAA historian on the Ploie?ti Unknowns Project. “There was a lot of scatter … some bailed, but most were killed as they were flying so low.”

Still, Romanian citizens worked to locate fallen airmen after the raid, burying them in the Civilian and Military Cemetery in Ploiesti and in 10 smaller cemeteries in nearby villages.

After the war, the American Graves Registration Command attempted to recover fallen Americans from across the European Theater.

There was a joint effort to exhume remains of U.S. airmen in and around Ploie?ti. German POWs were sometimes tasked with excavating the graves.

The conditions of the remains and their burials made identification harder. Evidence of each soldier’s identity — things like dog tags — was often missing.

Excavated remains were sent to France and Belgium for bone analysis to help determine height, weight, and age. Scientists studied what was left of the airmens’ mouths using fillings, cavities, and missing teeth to help with identification.

In the early 1950s, the U.S. government suspended its Return of the Dead program, pausing active searches to recover World War II remains. Some 80 U.S. airmen killed over Ploie?ti remained unidentified.

Many of their exhumed remains were stored in Belgium, where they were essentially untouched for nearly 50 years.

Today’s efforts

A 21st-century change in government policy opened the door to using forensics to identify soldiers’ bodies. That led the DPAA to launch the latest effort to exhume and identify the remains of Tidal Wave airmen in graves marked as “unknown.”

Cohn commended Romanian civilians for burying the fallen airmen during the war but said the way bodies were buried — sometimes with multiple bodies in one casket — complicates the identification process.

Cohn has spent the last several years doing in-depth research to build cases that the Department of Defense should approve the disinterment of specific remains by demonstrating that a successful identification is likely.

She studies the raid and peruses photos of remains, aerial imagery, maps and airmen’s files, using evidence and a lot of Excel spreadsheets to narrow down who each “unknown” airman could be.

When disinterment is approved, the skeletal remains are sent to anthropologists at a DPAA lab in Nebraska, where they examine the bones and try to match them to a specific file.

The lab team, led by DPAA scientist Megan Ingvoldstad, works with a U.S. Army genealogist to contact descendants believed to be related to specific missing airmen, sharing details and requesting DNA samples to compare to the skeletal remains.

The recent announcement of the identification of Lt. Col. Addison Baker was the 17th time the Unknowns Project team matched unidentified remains to an unaccounted-for Tidal Wave airman since the project began.

Baker, a 36-year-old pilot from Chicago, was commander of the 93rd Bombardment Group. As he approached his target over Ploesti, his B-24 was hit by an anti-aircraft shell and caught fire.

Instead of attempting an emergency landing, Baker continued leading his formation toward the target. After his crew unleashed their bombs, Baker veered away from the formation to avoid a collision and tried to climb high enough for his crew to bail. Despite the effort, all 10 crew members were killed. Baker received a posthumous Medal of Honor for his actions.

In April, Baker’s nephews — who knew their uncle before he went to war and provided DNA to confirm the identification of his remains — joined other family members and Army representatives to celebrate the news that Baker had been accounted for after 78 years.

Beyond the historical significance of the Unknowns Project, Cohn sees her team’s efforts as one important way to honor the ultimate sacrifice made by those airmen.

“It is very significant for me to be able to give closure to the families of the missing,” Cohn said. “It’s our responsibility to go out and find them and bring them home.”

© Copyright 2022 Business Insider. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.