Space Marines may sound like a far-off concept, but in some ways, they are already here. That’s because your average Marine infantry grunts would have a hard time doing their job these days without a constellation of satellites more than 1,000 miles overhead. Intelligence satellites provide aerial photos of their objective, communications satellites connect them with command and control, and GPS satellites allow them to call in airstrikes with pinpoint accuracy.

“Fundamentally, integrated air-land operations are completely space-enabled,” said Aaron Bateman, an assistant professor of history and international affairs at George Washington University who studies space policy. “That’s what’s at stake.”

Despite being mostly invisible to the naked eye, space assets have become so ingrained in everyday military life that it’s hard to imagine what it would be like to operate without them.

“When I look at my own experience as an Air Force intelligence officer in the Global War On Terror, people took space for granted,” Bateman said. “You could get sophisticated imagery intelligence or get missile warnings in Iraq whenever you needed. Nobody thought of the infrastructure supporting that. Military personnel are very much aware of products of space capabilities, but not the mechanisms that give them those products.”

Service members are not the only ones tied to space: most of the global economy is, too. GPS satellites alone play a significant role in everything from farming to banking to electrical power grid operation. Space plays a larger role in our everyday lives than it ever has before, and competition from space-faring countries like Russia and China “presents a serious threat to U.S. national security interests, including in space,” the White House wrote in its 2021 Space Priorities Framework. The growing threat was part of why the Space Force was formed on December 20, 2019.

“[I]t became clear there was a need for a military service focused solely on pursuing superiority in the space domain.” the Space Force wrote on its website.

But nearly three years later, many Americans still don’t understand what Space Force does, or they confuse it with the Netflix comedy series, or, as one Spirit Airlines employee showed late last year, they don’t even believe it exists. It’s tempting to joke about the Space Force, and Task & Purpose has done so several times. But the missions Space Force Guardians perform every day impact Americans more directly than perhaps any other service, and that is deadly serious.

Nothing new

Though the creation of the Space Force in 2019 has drawn more attention to the importance and vulnerability of satellites, the issue of how to protect those satellites has been debated by planners and policymakers in Washington for decades. The U.S. conducted the world’s first anti-satellite weapon test in 1959 and carried out subsequent ones during the Cold War. Both the U.S. and the Soviet Union used intelligence satellites to support tactical military operations since the 1970s, Bateman wrote in 2020 for War on the Rocks. In fact, many service members who became Space Force Guardians in the last two-and-a-half years are doing the same jobs they did before, just with blue name tapes on their chests instead of black or spice brown.

“We already had space forces, now we have a unified Space Force under one chain of command, instead of a bunch of fractured offices,” Todd Harrison, then-director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told The War Horse in 2020.

Like the Navy, the Air Force, and the other services, the Space Force does not actually command space operations. That job falls to the U.S. Space Command, which has been around, with starts and stops, since 1985. Space Command is the unified combatant command for all things space across the military, just like how U.S. Central Command oversees operations in the Middle East, and U.S. Cyber Command oversees operations in cyberspace. The Space Force’s job is to “organize, train, equip and provide forces and capabilities” for Space Command and other unified combatant commands that need it.

All this goes to show that U.S. military space operations have existed for decades, but the creation of the Space Force as a separate branch within the department of the Air Force centralizes that space culture and expertise.

“We needed a separate service to start developing a space culture, which just doesn’t exist in the Air Force,” Harrison added. “Operating a satellite is nothing like flying an airplane, and no one in the Space Force will go into space. But it will have a culture of people who understand the physics and the domain.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

Having that body of experts is more important now than ever before as the skies above grow crowded with government and commercial satellites.

“There’s a perception that space security anxieties are new, but they’re not,” said Bateman, pointing to past space scares in the 1970s and 1980s. “What we’re really seeing is a resurgence in space security concerns, rather than something completely new.”

What does the Space Force do all day?

The Navy sails boats, the Air Force flies planes, the Marine Corps eats crayons, but what do Space Force Guardians do all day? Part of what makes the service difficult to understand for many Americans is the lack of awareness of what’s involved in overseeing satellite networks.

“If you’re a ground pounder in the Army, you have a computer, so even if you don’t code, you have experience with computer networks and how important that is,” Bateman explained. “But because space capabilities are largely invisible, and the terminology of orbital mechanics is arcane, people have a hard time wrapping their minds around what space means for the warfighter.”

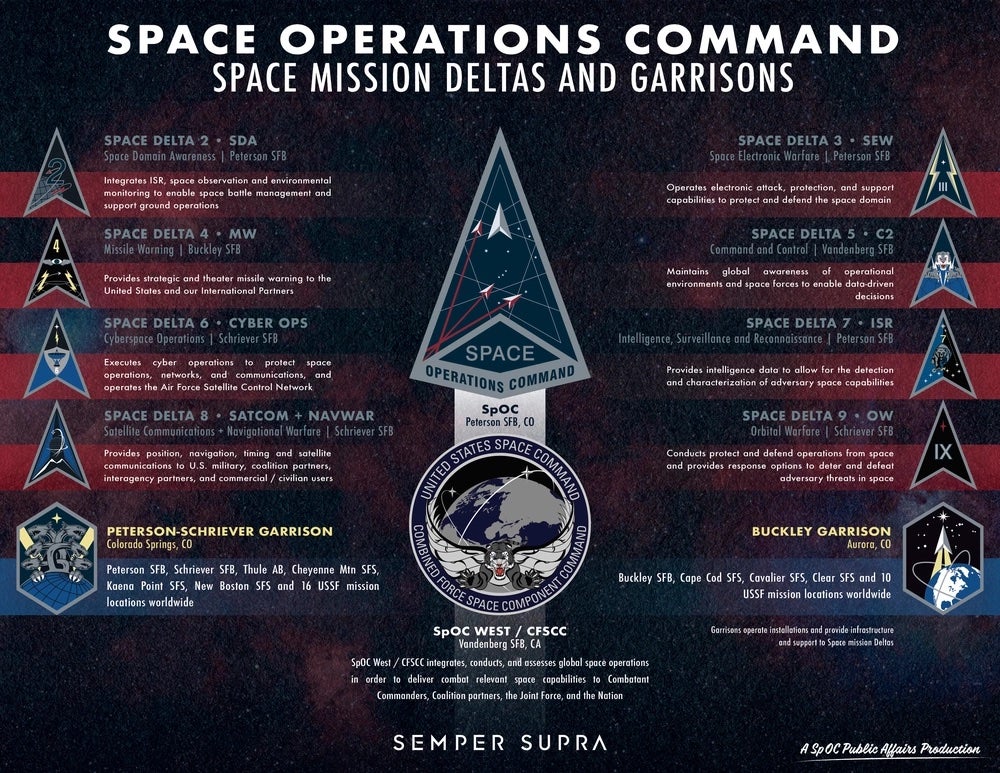

Luckily, the Space Force made a handy chart breaking down the service’s key capabilities. It may look like alphabet soup, but everything on it falls into one of several services Guardians provide, a few of which are listed below:

Missile warning

When Iran fired more than a dozen ballistic missiles at U.S. service members in Iraq in January 2020, American troops had crucial moments to prepare thanks to Space Force satellites that detected the missile launches and determined where they were headed. Chief of Space Operations Gen. John “Jay” Raymond gave a shout-out to Guardians at the 2nd Space Warning Squadron at Buckley Space Force Base, Colorado for the save.

“They operated the world’s best missile warning capabilities and they did outstanding work, and I’m very very proud of them,” Raymond said, according to Defense News.

The 2nd Space Warning Squadron is a component of Space Delta 4, whose sole purpose is to deliver missile warnings. A Delta is a little like a brigade in the Army, with each Delta led by a colonel and trained for specific missions and operations, according to Space News. Missile warnings involve not only space-based infrared system satellites like the ones used to detect the Iran missile launches but also ground-based systems like Upgraded Early Warning Radars and others highlighted at the bottom center of the Space Force chart.

“We need to be able to see what everyone is doing before they do it,” said Chief Master Sgt. Willie Frazier II, senior enlisted leader for Space Delta 4, in 2020. “The more warning we can provide, the better off we’ll be at detecting exactly where the threats are going to land, and then give our people ample forewarning.”

Space domain awareness

A good part of spacepower is knowing what’s happening up there. The Space Force operates both ground-based platforms, like the Ground-Based Electro-Optical Deep Space Surveillance System, and orbiting satellites like the Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program to keep an eye on anything from debris to spent rockets to other satellites. These eyes on the sky are impressive: GEODSS can track objects as small as a basketball more than 20,000 miles away, according to the Air Force. That level of detail is necessary to achieve space domain awareness, which involves both determining where space objects are located at a specific point in time and determining if they are potentially a threat, Bateman explained.

Though the purpose of the Space Force is to protect space assets, those space assets are vital to the operation of the military as a whole. Data generated from Space Force satellites gets sent to commands throughout the military, Bateman said. The Space Force keeps an eye on space and missile warnings. Meanwhile, the National Reconnaissance Office, an agency within the Department of Defense, builds and operates intelligence satellites, but other elements of the intelligence community “exploit” the raw intelligence coming off of the satellites, Bateman explained. NRO-gathered intelligence primarily takes the form of images and intercepted communication signals, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Satellite communication / Navigational warfare

A quick glance at the Space Force chart above shows that several of the satellites the Space Force operates involve navigation and communication. That includes the 31 GPS satellites which form one of the foundations of the modern economy; the Advanced Extremely High Frequency system, a constellation of satellites meant to provide jam-resistant communications for the president and top military leaders to talk with each other; and the Wideband Global SATCOM system, another constellation that provides the backbone of the military’s global satellite communications network.

Electronic warfare/cyber warfare

During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union both tested out systems for blowing up each other’s satellites, including one missile shot from an Air Force F-15 fighter jet that knocked out an old weather satellite in 1985. That kind of kinetic anti-satellite strike is frowned upon these days because of the hundreds or thousands of bits of debris it can send spilling across the orbital highway. That junk hurts everybody, including friendly satellites.

“There may be alternatives today that exist that are far more elegant and maybe just as effective, and maybe not as permanent,” retired Maj. Gen. Wilbert “Doug” Pearson Jr., the first and only Air Force pilot to shoot down a satellite, told Task & Purpose in 2020. “You have to ask yourself, do you really want to sink the ship, or do you just not want the ship near your base.”

Security analysts have warned that there is more than one way to neutralize a satellite. If access is available, hackers can take control of a satellite, deny an enemy access to its services, or even broadcast fake GPS signals that are disguised as real ones, Bateman explained in a 2020 War on the Rocks essay. The Space Force also has ground-based systems for jamming satellite transmissions, and the U.S. could consider investing in ground-based directed energy weapons (the umbrella term for weapons that use lasers, high-power radio frequency, and other directed energy technology) that can blind enemy intelligence satellites, Bateman said. C4ISRNET reported last year that the service is developing directed-energy systems to use in space, although Chief of Space Operations Gen. John “Jay” Raymond was mum about what specific operations these directed-energy systems could be put towards.

“Using non-kinetic counter-space capabilities can render a satellite unusable without creating debris, as is the case with kinetic anti-satellite weapons,” Bateman said. “An emphasis on non-kinetic weapons with reversible effects is more politically acceptable than debris-producing capabilities.”

The fog of space war

Each satellite is different, but for the most part, satellite operations are not very dynamic, Bateman told Task & Purpose.

“You don’t have someone flying it with a joystick,” he said. “It’s more health and safety checks and orbit adjustments, which is all done with computer command.”

The day-to-day operation of a satellite is more like maintaining critical infrastructure than flying an aircraft, he said. But, like a nuclear reactor or an electrical grid, keeping a close eye on satellite infrastructure is vital because so many people depend on it. The importance of satellites is one reason why they present such tempting targets for adversaries, but another reason is because it is sometimes difficult to gauge what counts as a hostile act. For example, it is sometimes not clear whether a GPS signal is being intentionally jammed or if it is a consequence of heavy radio frequency congestion in a particular area, Bateman explained.

“How do you determine what is a hostile act in space?” NBC News correspondent Tom Costello asked Maj. Gen. Shawn Bratton, head of Space Training and Readiness Command, in a recent documentary.

“We’re working through that now,” Bratton said. “We don’t have that history like we do in the other domains to build upon and so as we’re encountering these threatening activities for the first time. It’s forcing us to really define these terms.”

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine has proved, satellite networks are vulnerable in times of war. Russia has jammed GPS signals in Ukraine on and off since 2014, disrupting navigation and neutralizing Ukrainian drones used to locate the enemy and direct artillery fire, according to the Associated Press. While the Space Force would do its best to protect against these threats if the U.S. fought against such an enemy, the military overall may not enjoy the same uncontested satellite access it has grown accustomed to over the past several decades. One of the ways the military is preparing for that scenario is by teaching Navy midshipmen how to use sextants to navigate, which might be the only navigation tool available if GPS is down.

“It’s a return to learning more basic mechanisms, more basic techniques,” Bateman said.

The Space Force is less than three years old, and it still has plenty of room to grow. In March, a frustrated Guardian told Military.com that Space Force members have started using the phrase “semper soon,” a play on the service’s motto, “Semper Supra,” which means “Always Above.” According to the anonymous Guardian, Space Force members say “semper soon” when there is not a clear answer from leadership on rules, regulations and policies such as uniforms or physical training and it’s not clear when they will receive one. Robert Farley, a professor at the University of Kentucky who studies national security and intelligence, told Military.com that there were about five years of preparation before the second-youngest military service, the Air Force, was established in 1947.

“[C]ertainly, there was not the same level of preparation, in late 2018, that we had seen from the prior example of the establishment of the Air Force,” he said.

Some of that uncertainty goes all the way to the root of the Space Force, which is the question of what kind of objective policymakers want the new service to achieve. Many airpower experts use the term “air superiority” to describe a situation where friendly aircraft can move without prohibitive interference from opposing forces. It is tempting to adapt the same term to outer space in the form of “space superiority.” Even the White House used “superiority” to describe its goals in space in the quote mentioned earlier in this story. But with so many basic rules of space warfare, such as what even counts as space warfare, still in the works, policymakers need to be much more precise and intentional about the specific language and goals they use to form a space strategy, Bateman argued.

“If you want space superiority, what does that mean? What is the objective?” he asked. “Is it complete freedom of action in space? Before those terms are thrown around, we need to have a better discussion of what they mean. When policymakers use these terms they should be able to explain how objectives are to be accomplished.”

No matter what the policy ends up becoming, the 16,000 or so military and civilian members assigned to the Space Force will be keeping an eye to the sky, doing their best to ensure that space remains the ultimate safe space.

“It’s not space for the sake of space,” Bateman said. “It’s space for the sake of airmen, soldiers, sailors, and Marines who are in harm’s way.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.