At 95 years of age, Carl Elmer Jenkins is one profane Marine. His mordant memories of serving as a CIA paramilitary trainer in the combat zones of Vietnam, Indonesia, Laos and Cuba are salted with F-bombs and S-words about the A-holes he worked for. “What do you really think, sir?” is not a question a visiting reporter needs to ask Carl Jenkins.

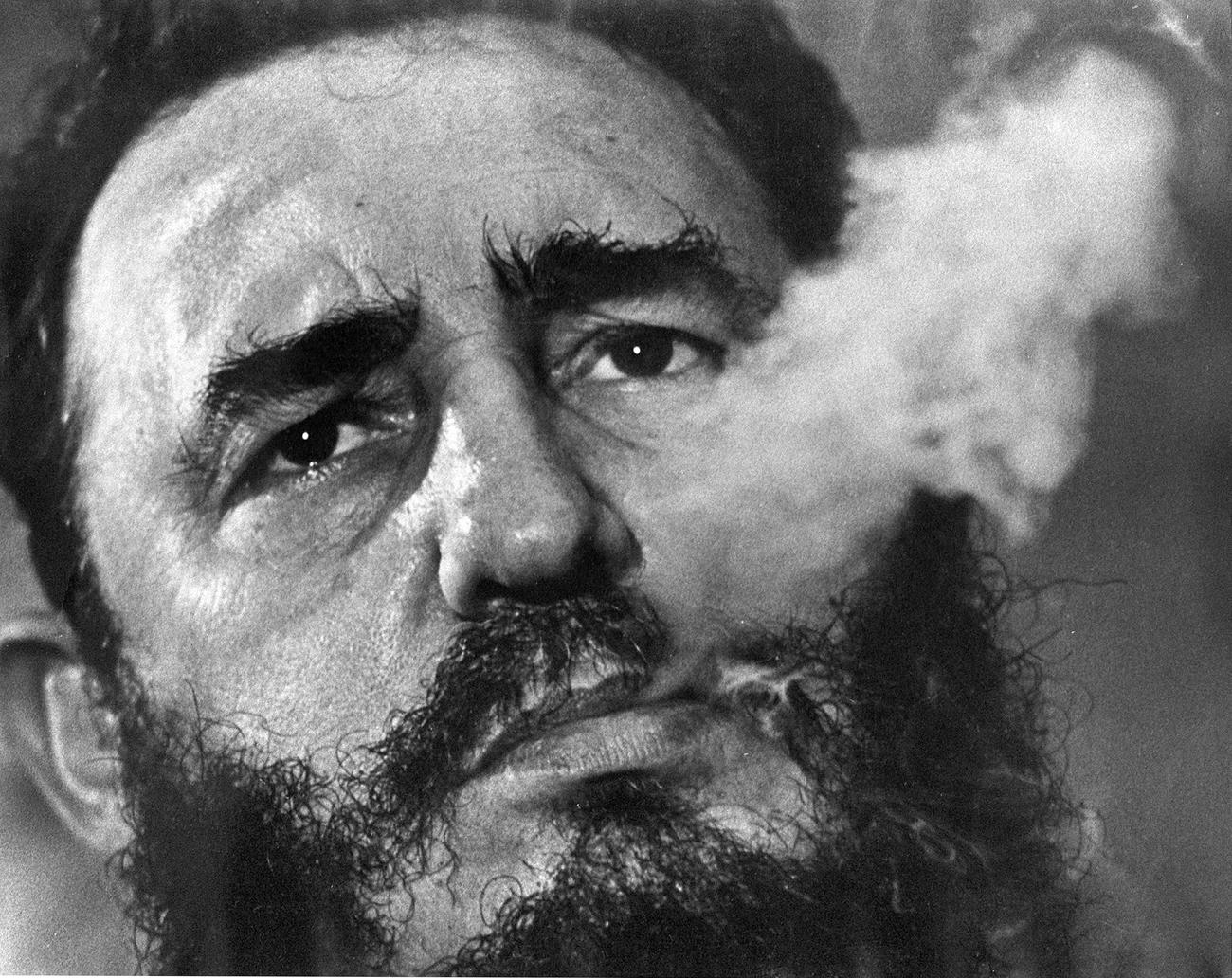

I first caught up with Jenkins in April 2021, having been drawn in by his legendary reputation. Over the next year, I wound up spending several days with him, spellbound by his stories. We sat at his dining room table, occasionally taking a break to stand on his patio. He trudged about the house with a cane, complained good-naturedly about the trials of old age, and did not hesitate to answer questions about his role in an infamous CIA plot to assassinate Cuban ruler Fidel Castro that fell apart five decades ago.

Jenkins grew up in a shack without indoor plumbing near Shreveport, Louisiana. After signing up for the Marines at age 17, he served in the Pacific during World War II, rising from private to staff sergeant. Upon his return, he went back to school and graduated from Centenary College. In 1950, he finished first among 372 officers in a Marine Corps training program at Quantico, Virginia. He joined the CIA in 1952 as a survival, evasion, resistance and escape instructor.

Read Next: Two US Vets Reportedly Captured by Russian Troops in Ukraine as Families Scramble to Learn More

Among his first assignments was training small teams for maritime infiltration of Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines. Then, he served as chief of a CIA base in Guatemala, where he trained the leaders of Brigade 2506, the U.S.-backed invasion force that was defeated at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba in April 1961. In his bedroom, Jenkins has a plaque from the brigade commending him “for outstanding services beyond the call of duty.”

In Vietnam, Jenkins served in Danang, organizing U.S. Special Forces to carry out sabotage attacks on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Later, he served as a top counterinsurgency adviser to governments in the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua. In 1971, he became chief of a CIA base in southern Laos, where he guided and trained 10,000-plus regular and guerrilla forces, while calling in the occasional B-52 Stratofortress strike. In retirement, he debriefed Cuban militants for the CIA and served as an unpaid consultant to President Ronald Reagan’s State Department during the Iran-Contra affair.

“I was one of the handful of people in the agency that was trained and experienced in paramilitary operations,” he told me. “I could indeed bring down a government. Or I could protect the government by getting rid of the insurgents. Either way. And the word goes around. ‘Hey, if you need a dirty job done, call Jenkins.’ And they did. And I went.”

Jenkins still swaggers in his war stories. He recalled how he and his first wife ran a U.S. military guesthouse in Danang while his Vietnamese girlfriend ran a bar across the street. “You never knew who was a communist in that city,” he sighed.

But he is no braggart, occasionally waxing doleful about his career in covert action. “I’ve had maybe three major successes,” he muttered, “and a hell of a lot of failures.”

I showed Jenkins a file of declassified cables about the AMLASH affair, a notorious CIA plot to kill Castro in the early 1960s. Jenkins’ name appeared in dozens of documents. As far as I knew, he was the last living American who participated in a covert operation whose disclosure led to fundamental changes at the CIA.

The revelation of the AMLASH plot in a 1976 report of Senate investigators proved to be a pivotal moment in the CIA’s history. Coming directly after the Watergate scandal, the disclosure that the agency had plotted to kill Castro — on the very day that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas — was a sensational news story, triggering public outrage, conspiratorial suspicions, and multiple investigations.

The CIA saw its secrets laid bare, its budget slashed, its reputation tarnished, and, as a result, congressional oversight of the agency was imposed. While Castro gloated, the agency’s public image took a hit that the men and women of Langley have always preferred to downplay, if not bury.

When I showed Jenkins the declassified file, first made public in 2018, he opened up with a colorful choice of words.

“Eisenhower did not want the Bay of Pigs and neither did I,” he scoffed, referencing the CIA’s ill-fated invasion plan in 1961. “I was chief of base on that f—ing operation.” President John F. Kennedy was “a loser,” he said, adding his brother Attorney General Robert Kennedy was worse. “Everything he touched, turned to s—.”

With the paper trail in front of him, Jenkins recalled the plot to kill Castro in fine detail, laying to rest any lingering historical controversy about who actually orchestrated the unsuccessful conspiracy to end the life of the Cuban communist leader who later died of natural causes in 2016 a few months after his 90th birthday.

Richard Helms, the gentlemanly CIA director with a reputation for keeping the darkest of secrets, insisted in his memoir and on Capitol Hill that the AMLASH operation was playing at tilting domestic politics in Cuba by fomenting political opposition.

“It was not an assassination operation,” Helms testified under oath to Congress. “It was not designed for that purpose. I think I do know what I’m talking about here.”

Historians have tended to take Helms’ denials at face value.

“When people wanted to invade Cuba or kill Castro, his attitude was, ‘Oh, God,'” Helms’ biographer Thomas Powers told Chris Whipple, author of “The Spymasters: How the CIA Directors Shape History and the Future,” a much-lauded 2020 profile of CIA directors.

“He just was so against it all,” said wife Cynthia Helms of the plots to kill Castro. “He said to me one day, ‘I was never going to do it. We were never going to do it.’ But they made his life miserable over it.”

Was AMLASH an assassination operation? I asked Jenkins.

“Of course,” snorted the retired Marine.

The AMLASH saga began late one night in October 1956 in the Montmartre, Havana’s swankiest nightclub. Two young men in the crowd pulled out pistols and shot dead Col. Antonio Blanco Rico, the chief of the Cuban military intelligence service, outside the club’s elevators.

One of the gunmen was Rolando Cubela, a medical student at the University of Havana who had taken up arms against the dictatorship of President Fulgencio Batista. After Castro and allied forces ousted Batista in 1959, Cubela assumed a series of senior positions in the new government. As a Catholic and nationalist, Cubela loathed Castro’s hard left turn toward one-party socialism.

The CIA men, who knew of Cubela’s armed exploits, targeted him for recruitment under the code name AMLASH. (All Cuba operations were identified by the AM diagraph, followed by a chosen noun; Castro was known as AMTHUG).

Helms sent an up-and-coming CIA officer, Nestor Sanchez, to Brazil to take over the handling of Cubela, who continued to have personal access to Castro. Sanchez was handing a poison pen to Cubela in a CIA safehouse in Paris on Nov. 22, 1963, when Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Sanchez, who would go on to hold senior positions in the CIA and Pentagon, was “a good friend,” Jenkins said.

When Jenkins returned from Vietnam to the Cuba program in early 1964, he was cleared into the AMLASH operation. Sanchez, he explained, was replaced as Cubela’s contact by Manuel “Manolo” Artime, a foe of Castro’s with a knack for charming U.S. officials. “Manolo was a perpetual juvenile … a guy who loved everybody and just assumed that everybody loved him,” Jenkins said.

In our interview, Jenkins reviewed five memos that he wrote about the AMLASH project in 1964, recalling that he had dictated them but never seen the paper copies. Another declassified memo showed that the CIA’s National Photographic Interpretation Center supported Jenkins on a “plan to assassinate Castro at the DuPont Varadero Beach Estate, east of Havana. Castro was known to frequent the estate and the plan was to use a high-powered rifle in the attempt.”

Jenkins said he voiced doubts about whether Cubela could be trusted. Having trained two former Castro bodyguards for Brigade 2506, “I knew pretty well what his habits were … what his intimate daily routine was like,” Jenkins said. He recalled asking Artime, “Who is this guy and what is he up to? You know, just exactly what are we dealing with here? Is this real or is this a trap of some sort?”

Jenkins’ caution was ignored and, when Artime and Cubela met in Madrid in December 1964, Cubela reiterated his demand for a weapon to kill Castro, specifically a Belgian-made FAL rifle.

“The FAL was the NATO rifle,” Jenkins explained. “It was easy to get ammunition for it. That was something I could do.”

Thanks to Jenkins’ arrangements, Artime delivered the weapon to Cubela in Cuba. When Cubela was arrested in March 1966 and charged with plotting to kill Castro, the FAL rifle was found in his possession. Cubela was sentenced to a 25-year jail term, of which he served only half.

Some have speculated that Cubela was a double agent for Castro all along. Castro denied that, and so did Helms. It was just about the only thing the revolutionary and the spymaster ever publicly agreed upon.

“I don’t accept the fact that he was working for anybody except Cubela,” Jenkins told me.

In any case, Jenkins’ first-person account of supplying the murder weapon, corroborated by CIA files, extinguishes Helms’ claim that AMLASH was not an assassination conspiracy.

“Just another busted operation,” the ex-Marine shrugged. As for Helms, “he was an a–hole as far as I’m concerned,” he growled.

— Jefferson Morley is author of “Scorpions’ Dance: The President, The Spymaster, and Watergate” (St. Martin’s Press), from which this article is drawn.

Related: American Veteran William Morgan Rose to the Highest Rank in Fidel Castro’s Army

© Copyright 2022 Military.com. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.