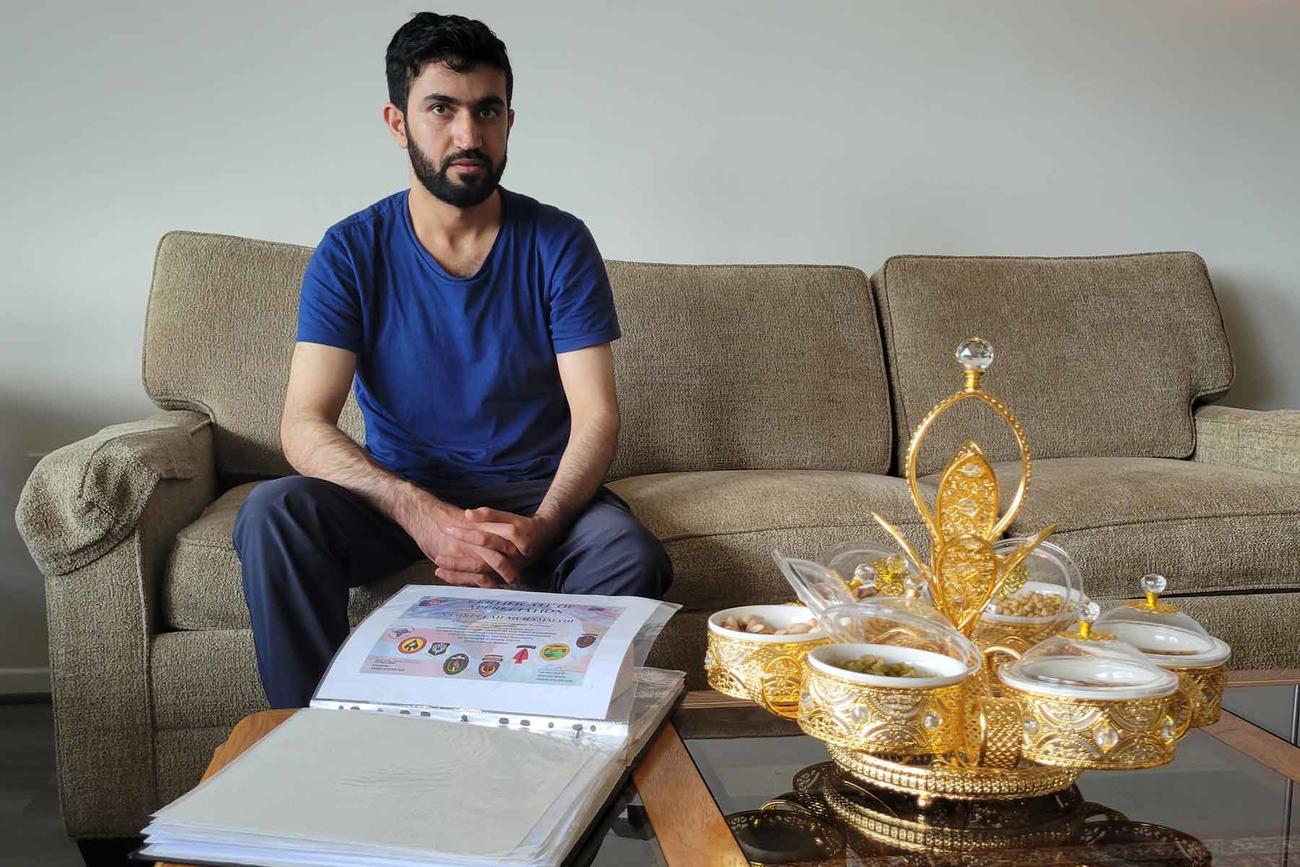

A golden tray with six bowls of nuts and dried fruit sits in the middle of Nasirullah Mohammadi and Zuhra Babakarkhil’s coffee table in their Falls Church, Virginia, apartment.

Over on an end table, there are two small, teardrop-shaped statues with the Arabic characters for Allah and Muhammad.

The statues and the decorative tray were among the first items Mohammadi and his wife, Babakarkhil, bought to add a touch of home to the one-bedroom apartment they’ve landed in after fleeing their native Afghanistan last summer.

Read Next: Soldier ‘Sextortion’ Cases Surged During the Pandemic, Army Statistics Show

It’s customary, Mohammadi explains, in Afghan homes to have a platter of dried fruit and nuts to offer to guests, and he and his wife wanted to carry on the tradition as they settle into their new lives in America. The couple also enjoys nibbling on the snacks themselves when they have tea, something the self-described “tea people” say they “always” do.

Less than a year earlier, the couple were in Kabul as the Taliban overran the city, undoing in a blink the United States’ 20-year experiment in shaping Afghanistan in its image.

Mohammadi recalls crying “all night” as he saw helicopters overhead ferrying U.S. diplomats to safety in August 2021 while he was in his Kabul home trying his best to avoid the Taliban.

Mohammadi, who is 24, worried about not just his own safety after working at and running bazaars on U.S. military bases for six years, but about what life would be like for a generation that had grown up not knowing Taliban rule.

Eventually, with the help of an in-law working at the Hamid Karzai International Airport, Mohammadi, his wife and several other in-laws made it onto U.S. military flights out of Afghanistan.

“There was like a tornado in my mind,” he said of his feelings when he left Afghanistan. “I left my business. I left my country. I left my house. Everything. But still I’m glad I saved my life, my wife’s life.”

Mohammadi and his wife don’t plan to stay in the Falls Church apartment for too long. A refugee resettlement agency is paying the rent right now, and $2,000 per month is too pricey for them when they’ll be paying on their own.

Mohammadi has found other worries in his new life. He’s busy taking care of family members who barely speak English while he tries to figure out how to become a legal permanent resident, a settled resolution to his temporary immigration status. Going back to school, getting a better job and buying a home are all on hold, for now.

But at least he’s safe.

“You have peace here,” he told Military.com during an interview at his apartment.

Mohammadi is one of more than 76,000 Afghans who were lucky enough to get on a U.S. military flight out of Kabul in August 2021 after the Taliban reclaimed control and government troops folded.

As the country Afghans like Mohammadi had known for a generation crumbled before them, the United States promised to be a refuge of “friendship and generosity,” as Secretary of State Antony Blinken phrased it.

“We have a long history in the United States of welcoming refugees into our country,” Blinken said while announcing new categories of visas for Afghans in early August as the Taliban was sweeping through provincial capitals. “And helping them resettle into new homes and new communities is the work of a huge network of state and local governments, NGOs, faith-based groups, advocacy groups, tens of thousands of volunteers. It’s a powerful demonstration of American friendship and generosity.”

Some of the evacuees, such as Mohammadi, had been unsuccessfully applying for years for visas to the United States, pointing to their assistance to the U.S. war effort that serves as one avenue to obtain permission to live in the U.S. permanently. Others were not formally what are called Special Immigrant Visa, or SIV, applicants, but still had connections to the U.S. military. Many were just people lucky enough to wade through the throngs of Afghans who crowded outside the Kabul airport hoping to make it onto a flight out and to a better life.

Nearly 10 months after arriving in the United States, the SIV applicants and others with U.S. military connections are living varying degrees of the elusive American dream.

Some are settling into their new lives smoothly, boosted by the kindness of both strangers and connections from their work alongside the U.S. military. Others are struggling, having arrived in the United States speaking little English, without any family or friends to rely on for help or feeling too uncomfortable to ask military buddies for aid.

The adjustments to life in the United States range from small cultural differences — such as Mohammadi being shocked to find out that stores in America accept returns or another evacuee’s confusion at people treating their pets like children — to big, life-altering struggles — such as figuring out how to become a legal permanent resident to finally have some stability after enduring 20 years of war, fleeing the only country they had ever known and landing in a new country half a world away.

Nassir Ahmad, a philanthropic adviser at Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, the resettlement agency that helped Mohammadi, said Afghan refugees’ “first worry” is whether they will be able to stay in the United States. Thousands of evacuees were brought to the United States under a temporary status known as humanitarian parole. The parole lasts two years, meaning the Afghans have a little more than a year left to sort out their immigration status.

“They don’t know if they’re going to be here for two years and then the United States government will kick them out or they will extend their parole for another two years,” said Ahmad, a native Afghan who himself came to the United States on an SIV in 2014 and jumped at the chance to help his fellow countrymen resettle. “They don’t know nothing, and that makes them struggle and that makes them think and overthink.”

Evacuees have also faced landlords unwilling to rent to people without jobs or rental histories, and the difficulty finding housing has stalled other progress on building a life, such as getting a job, Ahmad said. His clients also pepper him with questions ranging from how they can get driver’s licenses to where they can go to celebrate the Muslim holiday of Eid.

From Doctor to Construction Worker

Mohammed Abas is one of those finding it more difficult to adjust. Military.com is using a pseudonym at his request because his wife, children and parents are still in Afghanistan and he fears for their safety.

Abas’ English is limited — one of his in-laws who immigrated to the United States four years ago translated interview questions and answers for him — and he can’t get a job in the field he’s trained for because he needs new licensing to practice medicine in the United States.

For the last couple months, Abas has worked at a construction site for a high-rise building, hauling wood and other material for the builders. Sometimes, he gets to use his medical knowledge by offering tips on hygiene and safety. But the transition has not been “an easy thing,” he said.

“Starting completely a different thing that even you don’t know that much about … is of course difficult and challenging,” he said when asked about not being able to practice medicine. “But there is no choice.”

Abas was a doctor in Afghanistan, treating Americans through work with the State Department starting in 2003.

In 2015, he applied for an SIV and, by 2017, got as far as the medical exam, one of the last steps before being approved to come to the United States. But his wife was pregnant and his mother was sick, so they could not leave Afghanistan at that time.

His SIV case then languished until July 2021, when Afghanistan was getting more and more dangerous as the U.S. military was withdrawing while the Taliban was racking up battlefield wins. That month, he got an email from the U.S. Embassy in Kabul saying his case was being reactivated.

On Aug. 28 — two days before the end of the evacuation — Abas was told to come to the Kabul airport within 20 minutes, though his SIV application still hadn’t been approved. He started to bring his family to the airport too, but amid the crush of people trying to get to the gate and on the advice of an American coworker who warned about threats to the airport, the family turned back and he left alone. Two days earlier, an ISIS suicide bomber had killed 13 U.S. troops and 170 Afghans.

Abas is now living in a two-bedroom apartment in Alexandria, Virginia, with another evacuee whom Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service paired him up with. They both arrived in Alexandria after spending four months at Fort McCoy in Wisconsin and a few weeks at a hotel in Virginia while the resettlement agency found a place for them to live.

Bills are not a concern right now because the resettlement agency is covering rent on the $2,000 per month apartment and utilities. Abas said that will end in a couple months and that he has not thought about how will afford to live in Alexandria afterward, though Ahmad told Military.com the agency’s help will continue until he can afford to pay bills on his own.

Abas has looked into how to practice medicine in the United States and thinks he’ll start by trying to become a physician assistant since that will take less time than being a doctor, but even that requires years of schooling. He first plans to take English classes.

Weighing on him amid worries about job prospects and his family’s safety back in Afghanistan is the question of whether his future will be in the United States at all. Because his SIV wasn’t approved when he boarded the plane in Kabul, he was brought to the United States under humanitarian parole. He met lawyers when he was in Wisconsin who offered to help him apply for asylum.

Still, the struggles haven’t soured him on life in the United States.

“The U.S. is a nice place to live in because there are a lot of opportunities in this country. You can work, you can study and you can improve your future here,” he said.

‘The Top 1% of Afghan Refugees’

Afzal Afzali readily acknowledges he’s had an easier transition than many of the other Afghan evacuees.

“At least for me, it wasn’t that difficult,” he said in a phone interview with Military.com from his new home in Dallas, Texas. “That’s not the case for every Afghan evacuated.”

Afzali credits his success to contacts he made at the Pentagon and State Department when he worked at a U.S.-funded nongovernmental organization that helped promote U.S. programs in Afghanistan, contacts who also helped him, his wife and two children escape. Those contacts also begot more connections that offered help resettling.

“He’s truly in the top 1% of Afghan refugees,” said Scott Sadler, a communications contractor at the Pentagon, who is one of the people who has aided Afzali. “There were probably a lot of people that just felt like they did their due diligence by getting them out of Kabul and then the agencies would take care of them. The agencies were so overwhelmed.”

Media attention to Afzali’s escape — he escorted four unaccompanied children whose mother was already in New York — has also helped. One Dallas businessman who read a Dallas Morning News story ended up buying Afzali a car and renting him the three-bedroom, lake-adjacent house he and his family are living in.

Job offers also started coming for Afzali before he and his family even left Fort Bliss, Texas, where they were taken after evacuating, and he now works at pharmaceutical giant Pfizer.

Afzali’s 7-year-old daughter and 5-year-old son had some trouble adjusting; neither spoke English and they didn’t fully understand why they had to leave their home in Afghanistan.

Now, though, the children are in school, making friends and learning English; his daughter, especially, is learning quickly, he said. The family has also been going to the movies every other week, something they couldn’t do in Afghanistan. The kids’ favorite so far was the recent “Sonic the Hedgehog” sequel.

In May, Afzali was one of 13 Afghan refugees who met with former President George W. Bush. Afzali said he thanked Bush for making Afghanistan safe enough for him to go to university. Afzali also told Bush about his first experience with a Texas tradition — the Midnight Yell, a pep rally Texas A&M holds the night before football games — to what Afzali described as Bush’s “laughing out loud” amusement.

‘You Have to Have Future Plans’

Mohammadi, the evacuee who ran a bazaar for the U.S. military, applied for an SIV in 2017, but his case has been pending ever since. As the security situation in Afghanistan deteriorated in 2021, he and his wife, Babakarkhil, had planned to make their way to India, but got caught in Kabul when it fell.

In addition to working at Camp Morehead from 2015 to 2017 and Camp Duskin from 2017 to Kabul’s fall, Mohammadi worked as a lab technician and was studying for a political science degree in Afghanistan. Babakarkhil was just a month away from finishing college when the Taliban, which has severely restricted women’s education, took over.

After leaving Afghanistan, they spent four months at Fort Dix in New Jersey and a month at an Airbnb in Virginia, a wait extended in part by a Catch-22 of landlords not wanting to rent until Mohammadi had a job but him not being able to get a job until he knew where he was going to live.

He hasn’t wanted to reach out for help from anyone he knows from the U.S. military, worried they’ll think he’s just using them.

He now works at a coffee shop in the upscale Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. That job is part time, so he’s also been making money doing odd jobs such as DoorDash.

Babakarkhil’s parents, who speak barely any English, have been mostly homebound in an apartment five stories up from their daughter and son-in-law. They’ve been able to find some comforts from their home country, including on the day Military.com visited when the couple watched an old TV special for the Eid holiday on Afghan channel Tolo’s YouTube page.

Hanging over the family and thousands of other Afghans as they start to build a life in America is their immigration status.

Refugee advocacy groups, as well as several veterans organizations, have been pushing Congress to pass what they’re calling the Afghan Adjustment Act. Such a bill would provide a pathway for Afghan refugees in the United States to apply for legal permanent resident status, which humanitarian parole generally does not offer.

The Department of Homeland Security has estimated roughly 36,000 Afghans were brought to the United States under humanitarian parole during the August evacuation.

Congress passed similar legislation in the 1960s for Cubans fleeing the Castro regime; in the 1970s for Vietnamese and other South Asian refugees after the fall of Saigon; and for Iraqis after both Operation Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom. But there’s been little movement on doing so for Afghans who came last year.

The Biden administration gave a boost to the effort last month when it asked Congress to include the Afghan Adjustment Act in a Ukraine aid package. But the Afghan provision was not included in the final Ukraine bill signed into law amid Republican objections, and there has been no public talk since about moving it as a stand-alone bill.

Mohammadi has dreams of opening his own business, perhaps selling traditional Afghan clothes. Both he and Babakarkhil would also like to go back to school. First, she’s taking English classes. He’s also found they can’t get financial aid to afford college without being legal permanent residents.

“This is one of the most important things for us, getting permanent residency,” he said. “After that … we can make our decisions for the future. … For the life, you have to have future plans. You must take a higher step. We are stuck in one step all because of the permanent residency.”

— Rebecca Kheel can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @reporterkheel.

Related: White House Pushes for Afghan Refugee Relief After Visas Drop by 91%

© Copyright 2022 Military.com. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.