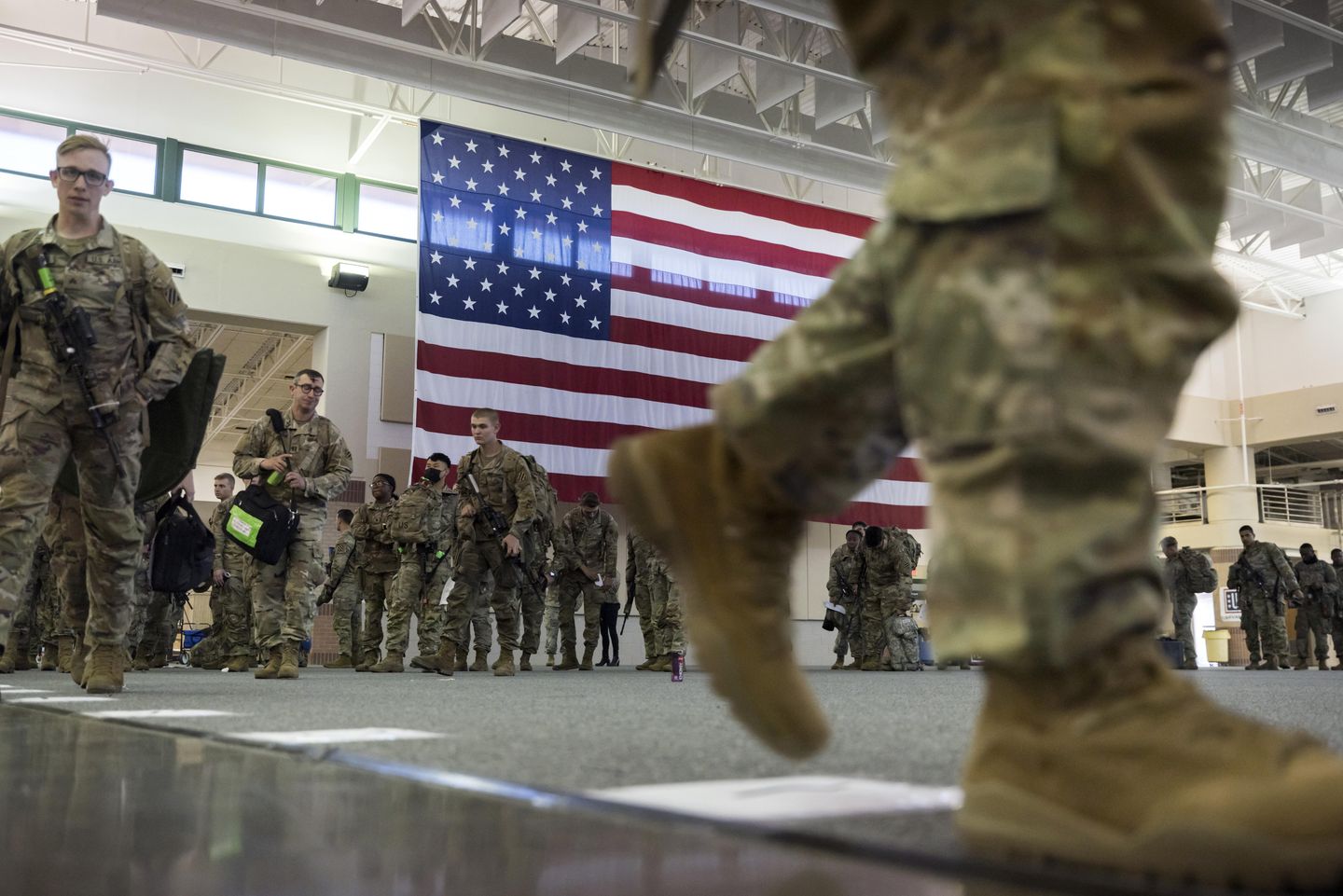

The number of American troops in Europe has risen sharply in the four months since Russia invaded Ukraine, jumping from about 65,000 in mid-February to 100,000 today.

But that increase, one of the most rapid U.S. military build-ups on the continent in the post-Cold War era, comes without a clear end date or any obvious metrics to determine when troops could come home or be repositioned to other key theaters such as the Indo-Pacific.

Instead, their mission is to deter further Russian aggression and prevent any attack on NATO territory — a goal that will prove difficult to measure and one that could potentially justify a years-long mission as Russia and Ukraine settle into a slow, bloody war of attrition in the Donbas.

The long-term consequences for the U.S. and its foreign policy priorities could be significant, some foreign policy analysts argue, as Washington likely can’t afford to keep up such troop levels in Europe over the long haul without sacrificing resources in the Pacific.

They say that the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s not-so-subtle threats toward Europe, should spark a renewed push inside NATO and the European Union to ramp up member nations’ defense spending and troop deployments on their own borders.

“We did what we had to do in the short term, following the February invasion, to deter an attack against NATO members,” said Bradley Bowman, senior director of the Center on Military and Political Power at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), a Washington think tank. “Unfortunately we have no idea how long this lasts. I think we can make a reasonable guess that what’s going on in Ukraine could go on for a very long time.”

SEE ALSO: G7 to ban Russian gold, as missile strikes continue in Ukraine

“I don’t want to send more forces than we need to Europe because they’re needed in the Indo-Pacific,” Mr. Bowman said. “We really need Europe to step up as much as possible to take the security burden off of our forces that are there as much as possible so we can allocate more of our finite resources elsewhere.”

Mr. Bowman conceded, however, that if the choice is between a ramped-up U.S. presence or inadequate protection for NATO’s eastern flank, “I choose to send U.S. forces.”

Those questions will be at the center of both public and private conversations this week when NATO members meet for a high-stakes summit in Madrid.

The debate over America’s long-term military presence in Europe has long been a politically divisive issue. It famously formed a cornerstone of former President Donald Trump’s foreign policy, as he relentlessly pushed European nations to spend more on their own security and remove some of the burden from the U.S.

His push was somewhat successful, as numerous NATO members increased annual defense spending past 2% of GDP, which has become the widely accepted target figure.

Mr. Trump’s effort to pull thousands of U.S. forces from Germany, however, was abandoned after President Biden came to power in January 2021.

‘It’s their backyard’

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sparked more defense spending increases, but even European leaders acknowledge that they’ve been too slow to bolster their militaries.

The figures are somewhat stunning, especially compared with the eye-popping defense spending increases seen in Moscow and Beijing.

From 1999 to 2021, EU combined defense spending increased by 20%, the European Commission said in a May 18 analysis. During that same time, defense spending increased by 66% in the U.S., 292% in Russia and a whopping 592% in China.

“Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has changed the security landscape in Europe. Many are increasing their defense spending, but it is crucial that member states invest better together to prevent further fragmentation and address existing shortfalls,” top EU diplomat Josep Borrell said in a statement accompanying that May 18 document. “If we want modern and interoperable European armed forces, we need to act now.”

In 2020, total EU defense spending amounted to 1.3% of the alliance’s GDP, according to European Commission figures. Key European nations — including Germany and Poland — have ramped up their defense budgets in the months since the war in Ukraine began. They’ve pledged to increase them further in the future.

But in the short term, there’s no clear substitute for American manpower, weapons and equipment in Europe, particularly in Poland and the Baltic states closest to the raging war in Ukraine.

The Pentagon so far has largely sidestepped questions about how long the current level of U.S. troops will be maintained in Europe, stressing that they’re there to deter Russian aggression and to demonstrate NATO solidarity.

Military analysts stress that such deterrence is crucial both for the security of Europe and for America’s long-term foreign policy challenges beyond the continent.

“To the extent China is seen as a major challenge, it is all the more reason that European security must be stabilized as an anchor of the future global order,” Michael O’Hanlon, senior fellow and director of research in foreign policy at the Brookings Institution, wrote in a June 21 analysis of U.S. and NATO defense postures in Europe.

“The United States and allies do not have the military, economic, or diplomatic bandwidth to address escalating crises and conflict in both Europe and Asia at the same time,” Mr. O’Hanlon wrote. “New crises and conflicts in Europe must be prevented before they begin, to the maximum extent possible.”

The twin dynamics in Europe and the Pacific will require close collaboration between the U.S. and its NATO allies, specialists say, in order to achieve maximum impact.

While some major European military players such as Britain and France are increasing their presence in the Pacific, others should focus almost entirely on Europe in order to take pressure off of U.S. forces, specialists argue.

“I really don’t need German vessels sailing through the Taiwan Strait,” said Mr. Bowman, the FDD analyst. “What do we need to defend Europe? We need air defense. We need long-range fires. We need [intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance]. Armored forces deter aggression along our flank. I’d like the Europeans to provide that as much as possible. It’s their backyard. If they don’t, we should. But we should be banging on them behind closed doors as much as possible to do it.”

Of the 100,000 U.S. troops in Europe, more than a third are on rotational deployment, meaning those service members are expected to remain on the continent for under a year.

“Prior to the unprovoked Russian invasion in Ukraine, there were approximately 65,000 permanently assigned U.S. service members in European Command,” U.S. European Command told The Washington Times in a statement. “There are currently 100,000 U.S. service members in the region. That includes approximately 35,000 scheduled rotational forces and additional forces ordered to the region by Secretary of Defense [Lloyd] Austin.”