Spc. 5 Dwight Birdwell didn’t want to die, but he was ready to as he fought his way through an enemy ambush at an air base near Saigon.

For Maj. John Duffy, calling in airstrikes from a location close to enemy positions even as he was wounded was just part of the job.

And when the children of Staff Sgt. Edward Kaneshiro heard their father had single-handedly cleared an enemy trench so his men could safely withdraw, they were inspired to “be a better person, to be courageous and to have integrity.”

Read Next: Space Force Launches New Intelligence Unit as Congress Voices Concerns over Growth

“He didn’t even think about himself,” Kaneshiro’s daughter, Naomi Viloria, told Military.com on Sunday. “He just had one mission, and that was trying to save his unit. It was duty to country.”

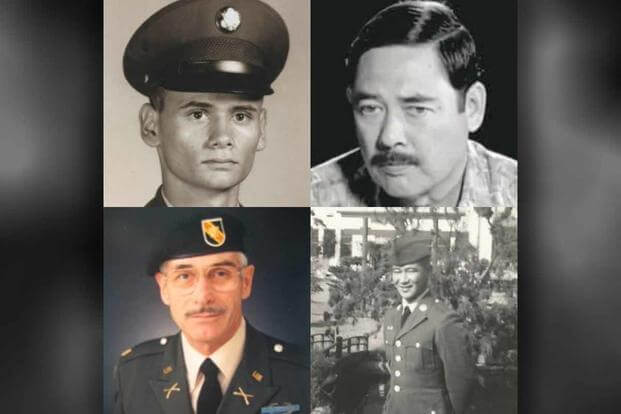

On Tuesday, Birdwell, Duffy and Kaneshiro, as well as Spc. 5 Dennis Fujii, were awarded the Medal of Honor by President Joe Biden for “acts of gallantry and intrepidity” during the Vietnam War, earning the nation’s highest military honor after a 50-year wait. For Kaneshiro, the honor is posthumous; he was killed on the battlefield months after his heroic actions.

During the White House ceremony, Biden said the medals were about “setting the record straight” and giving the Army veterans the level of recognition they deserve after so many years.

“There’s been a long journey to this day for those heroes and their families, and more than 50 years have passed — 50 years — since the jungles of Vietnam, where as young men, these soldiers first proved their mettle,” Biden said. “But time has not diminished their astonishing bravery, their selflessness in putting the lives of others ahead of their own, and the gratitude that we as a nation owe them.”

Birdwell, sharing his thoughts in a call with Military.com that included Viloria, her brother John, and Duffy, ahead of the ceremony, was stoic about the wait.

“Somebody told me long ago these things often take time,” he said.

Kaneshiro’s children, after reading in a newspaper that their father had first been recommended for a Medal of Honor in 1966, wrote a letter to their senator in 1990. When nothing came of that, they wrote another letter to a different senator in 2011.

Two weeks after his wife and their mother died in April, Kaneshiro’s children got a call that their father’s record was being reviewed and, a few weeks after that, Biden called to say he was getting the Medal of Honor, Viloria said during the phone call.

Their mother didn’t talk about her husband at all after he died because her “grief was just so profound,” but the children found out about his heroism from other family members and newspaper accounts, Viloria said. John Kaneshiro, who accepted the medal Tuesday on his family’s behalf, credited his father with inspiring his own service in the Army.

On Dec. 1, 1966, Kaneshiro and his team entered a village near Phu Huu 2 on a search-and-destroy mission. There, they were ambushed by a large North Vietnamese contingent that had fortified the village with a camouflaged trench and bunker system.

A hail of gunfire killed his platoon leader and several other soldiers, and two other squads were pinned down. Realizing the only way anyone would survive was to stop the gunfire, Kaneshiro directed his men to cover him and crawled alone toward the trench.

While still on the ground, he lobbed a grenade that killed the North Vietnamese gunner. Then, he hopped in the trench and worked his way down its entire 35-meter length, eliminating one group of enemy fighters with his rifle and two more enemy groups with grenades.

His actions were credited with allowing for the “orderly extradition and reorganization of the platoon which ultimately led to a successful withdrawal from the village,” according to the award citation read at the ceremony.

Kaneshiro continued serving in Vietnam until he was killed by enemy gunfire on March 6, 1967.

“Today, his memory lives on in the lives he saved, in the legend of his fearlessness and the hearts of the family he left behind,” Biden said. “Your family’s sacrificed so much for our country. I know that no award can ever make up for the loss of your father, for not having him there as you grew up. But I hope today, you take some pride and comfort in knowing his valor is finally receiving the full recognition it’s always deserved.”

As Birdwell reflected on getting the Medal of Honor, he expressed pride not for himself, but for the 25th Infantry Division and for the Cherokee Nation, of which he is a member.

“It brings honor and respect not only to the Cherokee Nation, but the Cherokee people,” said Birdwell, who served as the chief justice of the Cherokee Nation’s Supreme Court for a couple of years in the ’90s.

Birdwell’s award comes for actions on the first day of what would become known as the Tet Offensive.

On Jan. 31, 1968, a large element of North Vietnamese fighters attacked the Tan Son Nhut Air Base near Saigon, and Birdwell’s unit was ringed by enemy fighters. Most of his unit’s vehicles were destroyed or disabled, and his tank commander was incapacitated after being hit by enemy bullets.

Without hesitation, Birdwell moved the commander aside and took over, firing the tank’s cannon, machine gun and his rifle. When he used up all the ammunition in the tank, he dismounted and went to get two machine guns and ammunition from a helicopter that had been downed by enemy fire.

When his machine gun was hit by enemy fire and exploded, he was wounded, but refused to be evacuated and kept moving among disabled vehicles, collecting ammunition that he handed out to his brothers in arms. When reinforcements came, Birdwell helped evacuate the wounded until he was ordered to have his own wounds attended to.

“At the time, Birdwell received the Silver Star for his outstanding heroism on the battlefield,” Biden said. “It took decades for his commanding officer, then-Gen. Glenn Otis, to realize Birdwell had not received the full honor he had earned. But in retirement, Gen. Otis made sure to correct the record and fully document Birdwell’s actions to make this day possible.”

Birdwell said there was not much going through his mind during the battle besides “fight, fight, fight,” hoping to inflict as much damage on the enemy as possible and hold out until help arrived.

“We have a saying in Oklahoma, something to the effect of, ‘I want to go to heaven, but just not right now,'” he said. “And I was ready to die that day, but of course, I didn’t want to do it then because I knew if I went down, it would be easier for the enemy.”

Birdwell was not fazed about 54 years passing between his actions and receiving the Medal of Honor.

“There are still men alive who served on Jan. 31, 1968, and I’m happy to bring honor to them, and it validates what they did that day,” he said.

Duffy similarly brushed off the long wait to be honored.

“It was a different situation back then,” Duffy said. “The war was ending, American troops were pulling out, they were downplaying too much publicity, and they were trying to withdraw in an orderly manner. And we were the last of the fighters over there, the aircrews and advisers. So we understood the situation. And we were not there to make glory and gain a medal.”

Noting he was once nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in poetry, Biden called Duffy the “definition of a warrior poet and devotion to those he served with and those who serve our nation still.”

Duffy earned his medal for actions in a battle from April 14 to 15, 1972. Two days earlier, his battalion commander had been killed, the battalion command post was destroyed, and Duffy was twice wounded but refused to be evacuated.

Instead, on the morning of April 14 after efforts to establish a landing zone for resupply aircraft, Duffy moved close to anti-aircraft positions to call in airstrikes. He was again wounded, but still refused evacuation. When enemy fighters launched a ground assault and a barrage of artillery fire in the afternoon, Duffy moved from position to position to spot targets for gunship fire.

On the morning of April 15 after an enemy ambush, Duffy led troops, including many who were seriously wounded, to an evacuation area, where he continued to direct gunship fire to enemy positions and marked a landing zone for helicopters. He boarded a helicopter himself only after all the other evacuees were aboard and, once on the helicopter, assisted a couple of the wounded.

“That was our job, and that’s as simple as it is,” Duffy said of his mindset during the battle. “You’re in control. You don’t panic. You execute and make the best decisions.”

Fujii was awarded his medal for actions during a rescue mission in Laos and Vietnam from February 18 to 22, 1971.

Fujii was crew chief aboard a helicopter ambulance that took enemy fire and crash-landed in Laos. A second helicopter landed and took on everyone from the crash — except for Fujii. The enemy was directing fire at him, and he told the other helicopter to leave him despite being injured.

“I knew that there was no way I could make it from where I was into the chopper,” Fujii said in a 2018 interview released by the Army. “And the longer I stayed there and waited, I was putting everybody at risk so I just waved the bird off.”

Other efforts to retrieve him were called off because of heavy anti-aircraft fire. Fujii became the lone American on the battlefield and treated injuries of South Vietnamese allies throughout the night and next day.

Amid an enemy assault on the night of Feb. 19, Fujii found a radio transmitter and called in American gunships to help repel the attack. For 17 straight hours, he exposed himself to enemy fire to get better views of enemy troop positions and call in airstrikes.

“At times, the fighting became so vicious that Spc. 5 Fujii was forced to interrupt radio transmissions in order to place suppressive rifle fire on the enemy while in close quarters,” the citation read at Tuesday’s ceremony said.

A U.S. helicopter was finally able to reach him on Feb. 20, but was hit and forced to crash-land at a South Vietnamese base four kilometers from his original location. A “totally exhausted” Fujii was at the allied camp for another two days before he was finally evacuated to medical care, according to his citation.

“Fujii downplayed his own contributions and honored the skills of the allied Vietnamese troops he fought with, simply saying, ‘I like my job. I like to help other people who need help out there,'” Biden said. “It’s amazing. Today, Spc. 5 Fujii, we remember and we celebrate just how many people you helped.”

— Rebecca Kheel can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @reporterkheel

Related: WWII Medal of Honor Recipient to Lie in Honor at US Capitol

© Copyright 2022 Military.com. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.