An Oregon Army National Guard helicopter crew took the phrase “cliffhanger” literally this weekend when they landed a 65-foot long Black Hawk helicopter on a snowy ridge line about two-to-three feet wide in order to rescue an injured mountain climber. The precarious landing took place on Saturday and was part of a rescue effort for a 43-year-old man climbing Mt. Hood, a volcano east of Portland, Oregon.

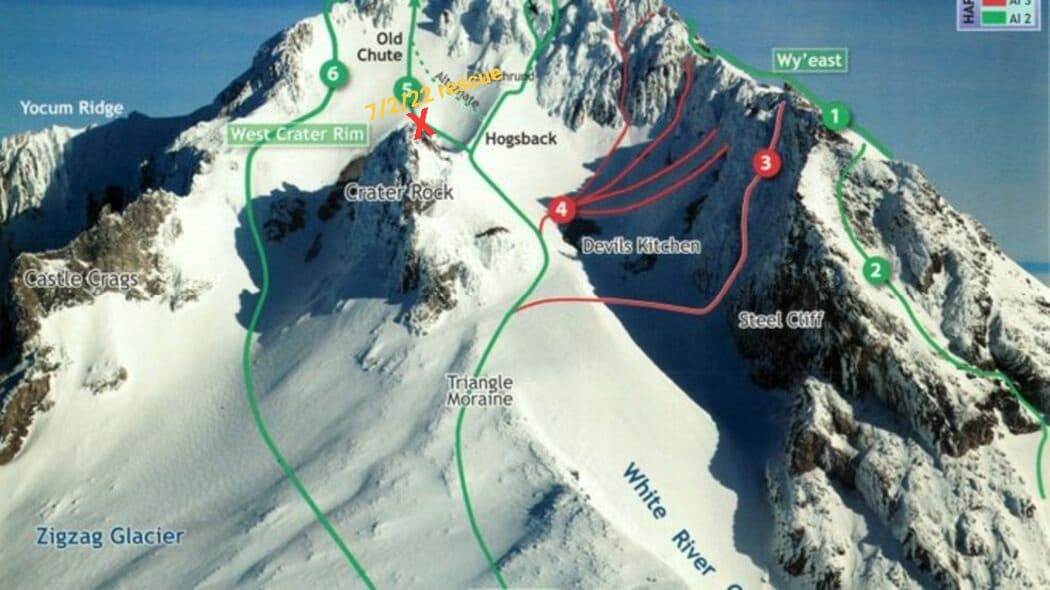

According to a Clackamas County Sheriff’s Office press release, the man lost his ice ax, fell 600 to 700 feet, and sustained serious injuries at around 6:30 that morning. Professional and volunteer searchers combed the mountain before reaching the injured climber about four hours later. At around 1:00 p.m. the Oregon National Guard helicopter arrived and dropped off two medics who packed the patient onto a litter, then later hoisted him into the helicopter, which then flew him to a Portland-area hospital.

Chief Warrant Officer 3 Michael Newgard, one of the pilots in the Black Hawk that day, said the ridge line landing took place so that the crew could drop off their two medics and let them get to work. The patient was located about 200 feet away from the landing site, he said, “and it would’ve been too dangerous for them to carry the patient uphill and across that ridge to load them.”

After dropping off the medics, the helicopter crew tried to land at a flat spot a few hundred feet below called Devils Kitchen. The plan was to land and save fuel until the medics were ready to call the aircraft back for a hoist pick-up. Turns out, Devils Kitchen was not a great place to land a helicopter.

“As we took power out, we began to sink slowly, so we discontinued that,” Newgard said. “We ended up finding out there’s a small lake or pond underneath the snow we were trying to land on and it would’ve been a horrible idea.”

Instead, the crew took off again and loitered in the air at 63 knots (about 72 miles per hour), which Newgard said was the “max endurance airspeed,” the airspeed that would get them the most time on station based on the temperature, altitude and aircraft weight that day. When the medics were ready, the crew flew back and conducted a hoist, bringing the patient up and flying him to the hospital right in the nick of time.

“It was a very rewarding mission to go on because we just got the patient to the hospital literally just in time as his vitals rapidly deteriorated en route,” Newgard said.

It definitely catches one’s attention to see a large, expensive military helicopter balanced precariously on a razor’s edge while its nose and tail hang over a steep snowy slope. As dangerous as it looks, the photo shows a type of landing that military helicopter crews have to perform somewhat regularly while flying in the mountains. Last July, a CH-47 Chinook crew with the California Army National Guard performed a “pinnacle landing,” where they balanced the helicopter’s back two wheels on some rocks on the slopes of Mt. Whitney while the front of the helicopter remained hovering in the air over a precipice. Unlike most modern cars, Chinooks don’t have backup cameras, so a landing like that requires complete trust between the pilots and the crew directing them. The Mt. Hood mission probably required a similar level of teamwork, one Army Black Hawk pilot told Task & Purpose.

“The crew chief would have played a big role in helping set the main wheels where they are,” said the Black Hawk pilot, who spoke with Task & Purpose on the condition his name not be used as he was not cleared to speak to the media. “The pilots up front have no visual on anything past their 9 and 3 o’clock positions, so the crew chief would have been the one to direct the pilots on the flight control inputs necessary to accomplish a landing like this.”

The Chinook pilot in the incident last July, Chief Warrant Officer 3 Aaron Mello, said the balancing act was like “riding a unicycle and trying to juggle,” at the same time. But the tight landing site is not the only challenge with pinnacle landings. Mountain flying means there is often a lot of wind making it difficult to hold the aircraft steady.

“All landings in high altitudes are challenging all the time,” Chief Warrant Officer 3 Charlie Mock, a Black Hawk pilot from the 25th Combat Aviation Brigade, said in 2012. “Throw a gust of wind in during a one or two-wheeled landing at 8,000 feet and things tend to become complicated.”

The high altitude also means that there is not much air to feed the helicopter’s turbine engines, which means the aircraft’s performance takes a hit. It also means the rotor blades have less air to bite into, so they cannot generate as much lift as they can at lower altitudes. The margin of error in those conditions is much lower than usual, according to a 2012 Army press release. Still, some pilots enjoy the challenge.

“The most enjoyable flight portion of flying the Chinook is doing a two-wheel pinnacle, where we land on top of the mountaintop and only put the ramp and the two wheels on the ground and have troops run off the back as the front of my helicopter is hanging off a cliffside,” Chief Warrant Officer 2 Waitman Kapaldo, a tactical operations officer with the 12th Cavalry Division, said in 2018.

On the Mt. Hood mission, the Oregon pilots likely would have needed to keep the aircraft at a power setting lower than a hover, but higher than a full landing explained the anonymous Black Hawk pilot.

“This would have had to be done manually because there is no autopilot function for such a maneuver,” he said. “The pilots would also had to have corrected for any wind affecting the aircraft’s position on the ridge.”

Given that many helicopter crews trained in search and rescue have the capability to simply hoist their patients up with a cable and a litter, a pinnacle landing may seem unnecessary, but it’s not. Jeff Nolan, a former Navy helicopter pilot, explained that when it comes to helicopters, it’s always a question of power. It takes a lot of power to keep a helicopter in a hover, he said, especially at altitude like the kind found over Mt. Hood. Hoisting a patient up on a litter takes even more power, which is risky when there is not much left to spare that high up in the air.

“The higher you go, there are less efficiencies, and the margin between power available and power required shrinks,” Nolan said. “When power required is greater than power available, then your bank account is empty.”

You can see the power savings in the photo and Facebook video of the Mt. Hood landing. Nolan pointed out that there is not a lot of snow blowing around the helicopter, which indicates the rotors are not spinning at a high level of power. The reason they are not spinning at high power is that the Black Hawk crew likely found something solid to rest their two belly landing wheels on while the search and rescue teams load the patient, Nolan said.

“You’d rather step out onto terra firma rather than hoist up, which requires a lot of power in a high hover,” he explained.

Landing is comparatively less power-intensive than hovering, even if it’s just on a wheel or two, Nolan said. That’s why military helicopter crews often practice one, two, or three-wheel landings, especially when they are assigned to the Oregon Army National Guard or other units that regularly pluck stranded or injured hikers out of the mountains.

“Any unit that is going to do search and rescue will train to the environment they’re going to be in,” Nolan said. “And those Oregon National Guardsmen fly around Mt. Hood a lot.”

That experience builds up so that if search and rescue teams on the ground need an Oregon National Guard helicopter to save the day, the helicopter crews are likely very familiar with the power calculations they need to make in order to fly at the altitude, weather conditions and aircraft weight they are working with that day.

“I would definitely say they are very well-trained,” Nolan said. “They’re going to punch their numbers very thoroughly.”

Newgard, one of the pilots on Mt. Hood that day, said the mountain is always a challenge for flight crews.

“Any mission at that height on Mt. Hood is precarious, even in great conditions that mountain has its own weather system and conditions can change instantly,” he said. “We put together an experienced crew to do the mission, whereas on some of our lower altitude missions we might have newer crew members take part to get experience.”

Even with the most experienced crew members, it takes a lot of teamwork to pull off a mission like that safely. The job was a “total team effort by our pilots, crew chief, and medics and the first responders on the ground to make it all happen,” he said. “Big recognition to Portland Mountain Rescue, the Hood River Crag Rats, and [American Medical Response], who took care of the patient before we could get there.”

A fellow helicopter pilot in the search-and-rescue community saluted the Oregon crew for their great work.

“Outstanding job by the Oregon Army National Guard crew. Mountain flying, and particularly Mt Hood can be treacherous,” said Air Force Lt. Col. Brough McDonald. Winds, high altitude, and having to hover in a pinnacle landing without hard surfaces beneath for rotor downwash to bounce up from and help generate lift, “all contribute to some of the most challenging vertical lift flying in the business,” he said.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, a pinnacle is an area “from which the surface drops away steeply on all sides,” while a ridgeline is “a long area from which the surface drops away steeply on one or two sides.” The landing at Mt. Hood in Oregon last weekend appears to have been a ridgeline operation, but a ridgeline landing presents similar challenges as a pinnacle landing, and the two are grouped together in the Federal Aviation Administration’s helicopter flying handbook.

“Updrafts, downdrafts, and turbulence, together with unsuitable terrain in which to make a forced landing, may still present extreme hazards,” the FAA wrote.

The FAA advises pilots to approach such terrain at the speed of “a brisk walk,” and to keep the approach angle steady the whole time. Like with many difficult tasks, slow and steady seem to be the trick. Keep in mind that the stakes are high: if the crew makes a mistake and the aircraft crashes, it could dramatically increase the number of patients in need of evacuation and complicate the rescue mission.

Thankfully, the Oregon National Guardsmen knew what they were doing, and they managed to touch down and take off without incident. That probably speaks to the amount of training Army pilots receive for this sort of thing.

“We do pinnacle landings all the time during training,” said Chief Warrant Officer 4 Stephen Lodge, who flew the OH-58D Kiowa Warrior helicopter, in 2012. “At 7,000 feet using [night vision] goggles with limited power to land in a small area is challenging for every aviator. When performing a pinnacle landing, the approach angle is critical with little to no margin of error.”

Correction: This story has been corrected to clarify that the Oregon crew landed on the ridgeline to drop off the medics, then later picked up the patient via hoist. The story has also been updated with comments from Lt. Col. Brough McDonald.

The latest on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.