President Biden was slow during his first year in office to embrace the significance of the Abraham Accords that the Trump administration brokered in the Middle East to achieve historic diplomatic normalization between Israel and several Arab powers.

Mr. Biden also vowed on the campaign trail that, as president, he would make Saudi Arabia a “pariah” over the 2018 killing of U.S.-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi, whose death U.S. intelligence officials have said was likely ordered by Saudi Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman (MBS).

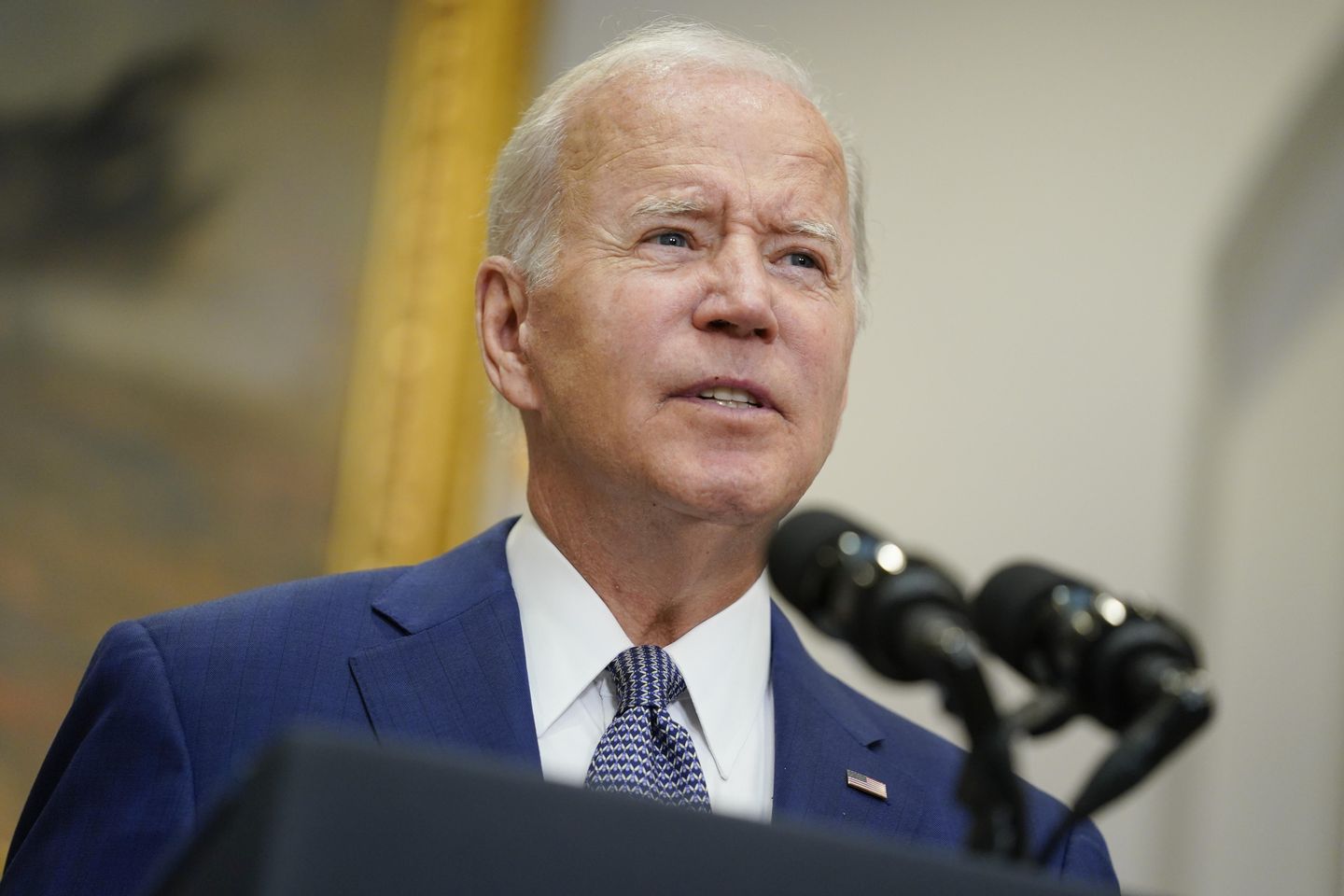

But since being elected, Mr. Biden’s posture has shifted a lot. And now, as he heads out on his first presidential trip to the Middle East, officials say he plans to celebrate the Abraham Accords, while also honoring the Saudis with a personal visit to try to persuade the crown prince to pump more oil in hopes of reversing soaring gasoline prices in the United States.

Regional experts say there are will be tricky issues at every turn of the July 13-16 trip that begins with stops in Israel and the West Bank, during which Mr. Biden will meet separately with Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennet and Palestinian Authority leaders, including Mahmoud Abbas, before traveling to Saudi Arabia.

While there is no guarantee the Saudis will agree to increase their crude oil production, analysts say a key behind-the-scenes aspect of meetings slated for the end of the week in Jeddah will be to ease Saudi frustration over Mr. Biden’s attempts during the past 18 months to restore the Obama-era nuclear deal with Saudi Arabia’s main regional rival, Iran.

More broadly, administration officials say that an overall goal of the Mideast trip will be to promote stronger security coordination among Arab powers, including the Saudis, and Israel — a once unthinkable pursuit that has become an increasingly viable objective amid shared Arab and Israeli concern over threats emanating from Iran.

With the Biden administration’s push for an Iranian-U.S. diplomatic detente having failed over the past year, national security insiders say the president is now focused on facilitating regional military preparedness for the prospect of an increasingly belligerent and perhaps even nuclear-armed Tehran.

U.S. lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have been pushing for such an approach for some time, with Republican and Democratic lawmakers having recently introduced legislation that would direct the Pentagon to shape a joint air defense system for Israel and Arab nations against Iranian ballistic missiles and drones.

National Security Council spokesman John Kirby has told reporters that the U.S. is focused on stressing coordination of regional air defense systems “so there really is effective coverage to deal with Iran.”

But it remains to be seen whether the Saudis are ready to openly embrace such coordination with Israel.

The Abraham Accords spurred unprecedented recognition of Israel by the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan.

However, others, including Qatar, which hosts a key U.S. military base in the region, and Saudi Arabia, which is widely regarded as the most economically influential of the Arab powers, have refused to normalize ties with Israelis.

Mr. Biden hopes to inch the ball forward. The president stressed in an op-ed published over the weekend by The Washington Post — the same pages where Khashoggi penned criticism of Saudi leaders — that he will be the first American president to fly from Israel directly to Saudi Arabia, describing the move as a “small symbol” of the Arab world’s gradual acceptance of Israel.

Mr. Biden used the op-ed to declare that the Middle East has become more “stable and secure” in his nearly 18 months in office, and he pushed back against the notion that his visit to Saudi Arabia amounts to backsliding.

“In Saudi Arabia, we reversed the blank-check policy we inherited,” he wrote in a slap at the former Trump administration, which pursued closer ties with the Saudis.

The president also touted his administration’s efforts to push a Saudi-led coalition to agree to a U.N.-brokered cease-fire with Iran-backed Houthi militants in Yemen. The cease-fire is now in its fourth month after seven years of a war that has left 150,000 people dead in Yemen.

But regional experts predict Mr. Biden will struggle to produce a major foreign policy success on his trip.

He is likely to be upstaged by local politics in Israel, where Israeli lawmakers recently voted to dissolve the parliament, paving the way for a fifth election in four years. And in Saudi Arabia, meetings are expected to be anything but easy.

“I don’t think the Saudis are going to announce they’re going to produce as much oil as quickly as they can to bring prices down, and I don’t think they’re going to recognize Israel,” said Jon B. Alterman, who heads the Middle East program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

Mr. Biden is still likely to try to present a united front with the Saudis, despite having previously vowed to play hardball with them in response to demands by many in the U.S. to call Riyadh out for human rights abuses following the Khashoggi slaying.

“There are a lot of good reasons, political and practical, for the president to take the position on Saudi Arabia he did two years ago,” Mr. Alterman told reporters on a conference call last week. “But as his administration has sought to advance a series of U.S. interests in the Middle East, it discovered what U.S. administrations have discovered for decades: that doing a lot of things in the Middle East and around the world are much easier if the Saudis are trying to help you and much harder if they aren’t.”

Others have stressed that Mr. Biden’s trip is coming at a delicate moment for the region and the world.

“A key objective for this trip is to send a signal that the United States remains committed to the region at a time of geopolitical uncertainty,” according to a pre-trip analysis published by the Middle East Institute that emphasized the backdrop of spiking energy costs not only in the United States, but worldwide.

“The Russian war on Ukraine has driven up energy prices globally,” wrote Paul Salem, the think tank’s president, and Brian Katulis, its vice president for policy.

“This has been a boon to energy exporters in the Gulf but has put an enormous strain on energy importers across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), including Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, and Yemen,” they wrote. “The energy importers have also been hit hard by a spike in food prices, as the war in Ukraine has exacerbated previous inflationary trends driving up the cost of key staples like bread.”

Mr. Salem and Mr. Katulis also pointed to the complexity of regional tensions “between Iran on the one hand and Israel and a number of Arab Gulf countries on the other.”

The U.S. push to expand coordination between Israeli and Arab militaries, meanwhile, has spurred debates over the extent to which such efforts will succeed in strengthening defenses against Iran or could make a regional war more likely.

Israeli-Arab security overtures have multiplied since the 2020 Abraham Accords.

The Associated Press has asserted that the overtures have grown further since the Pentagon switched coordination with Israel from U.S. European Command to U.S. Central Command, or CENTCOM, last year — a move that grouped Israel’s military with former Arab opponents, including Saudi Arabia and other nations that have yet to recognize Israel.

The news agency cited former U.S. Ambassador to Israel Daniel Shapiro as saying that for Arab and Israeli leaders, “the No. 1 motivator is the common threat they both perceive from Iran and Iranian proxies.”

Especially to the extent Saudi Arabia comes on board, the security ties under CENTCOM raise prospects of a “truly unified Sunni Arab coalition to stand with Israel” against Shiite-led Iran, said Mr. Shapiro, a prominent advocate of the emerging coalition between Israel and individual Arab nations.

Israel considers Iran its greatest enemy, citing its nuclear program, military activities and support for hostile militant groups. Gulf Arab states allied to the U.S. have long been wary of Iran’s support of militias and proxies. While lacking American-made sophisticated weaponry, Iran has an unmatched arsenal of ballistic missiles, drones and other arms.

Promoting greater regional integration with Israel’s modern military could soothe Saudi and Emirati complaints the U.S. is not doing enough to protect them from Iran. It potentially accustoms Arab nations to working with Israel, despite Israel’s failure to reach the kind of political resolution with the Palestinians that Arab nations long demanded as a condition for recognizing Israel.

The U.S. also hopes the coordination will mean that regional actors will take more responsibility for their own security, allowing the U.S. to ease its decades-long safeguarding of Arab oilfields and turn more attention to Russia and China.

• This article is based in part on wire service reports.