On the list of things the U.S. military has given civilian society, like sliced bread, duct tape, and microwave ovens, you can now add custom motorcycles otherwise known as “choppers.”

Often distinguished by their elongated handlebars and stretched-out front ends, choppers can trace their roots all the way back to World War II, when the son of William Harley, co-founder of Harley-Davidson, was training soldiers at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Decades prior, Harley-Davidson began in 1903 when William Harley and Arthur and Walter Davidson worked to build their first bike. Within just a few years the team was moving into their first factory, and in 1907, they began selling their motorcycles to police departments. Their production continued to increase, and in World War I, Harley-Davidson produced over 20,000 motorcycles for the military, according to the Las Vegas Harley-Davidson website.

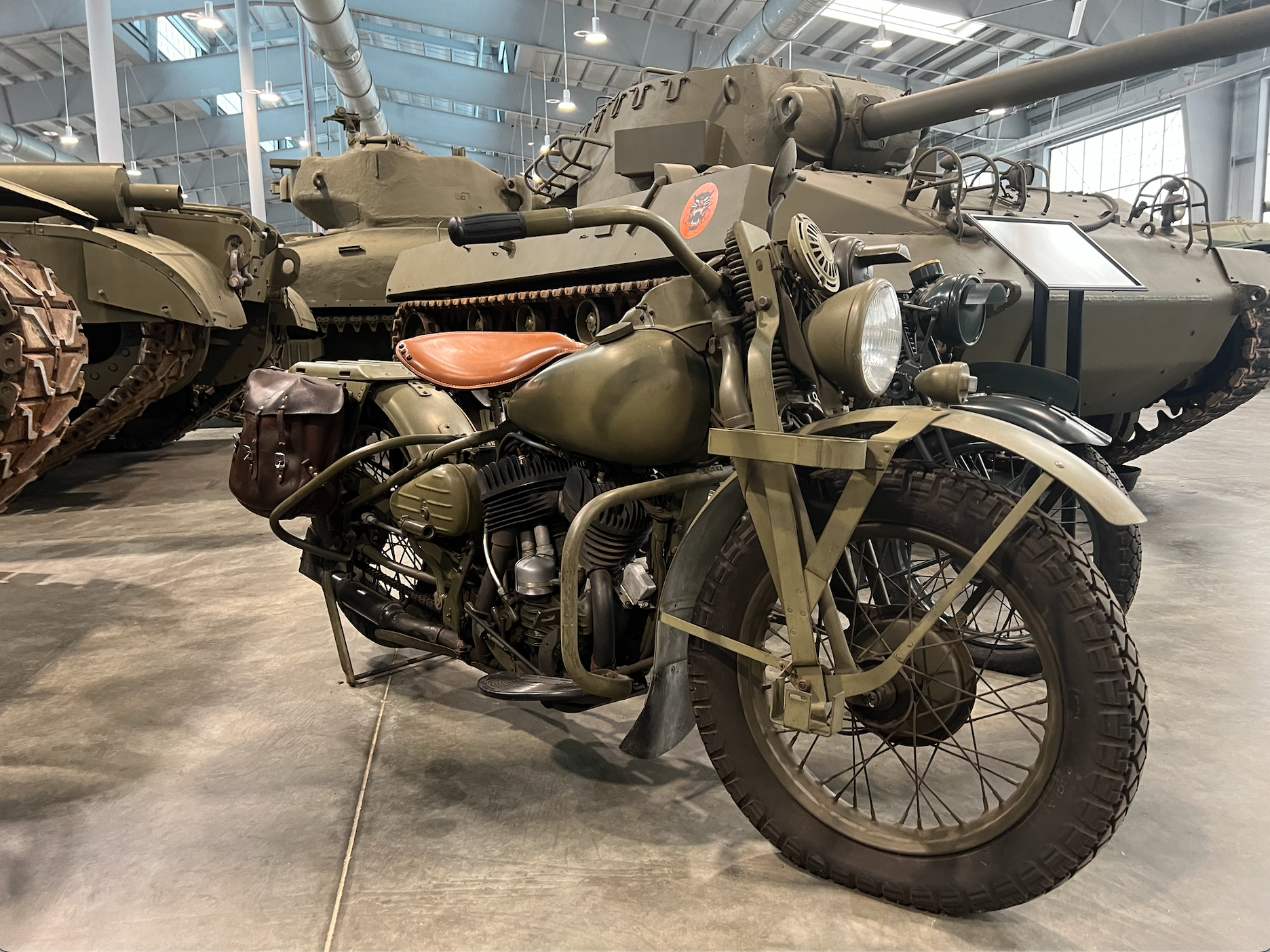

That production more than tripled during World War II, when the company produced more than 90,000 bikes for the military. These military bikes offered an unprecedented level of mobility and maneuverability for transportation and scouting, all in a package that was easy to move from place to place.

Rob Cogan, a collection curator at the U.S. Army Armor and Cavalry Collection at Fort Benning, Georgia, told Task & Purpose in April that Harley-Davidson first started building bikes for the U.S. Army in the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, the Army cavalry branch was buying up “tons of motorcycles,” Cogan said. Between the 1930s and 1940s around a third of Army cavalry scouts were on motorcycles.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

Among Fort Benning’s collection, housed in a giant warehouse on-post, are two motorcycles, one of which is believed to be one of the last the Army bought. It’s in nearly perfect condition, Cogan said, with only 11 hours on the engine. The motorcycle next to it is a British BSA, which the British Army used around the same time.

“When you tell young scouts today, they’re like ‘Oh man why aren’t we on motorcycles?’ And it seems really great until you realize it has no major weapons systems, it has no armor on it, especially when during this timeframe it couldn’t carry the heavy radios they had,” Cogan said.

During World War II, cavalry scouts were trained on motorcycles for various purposes outside of reconnaissance, including providing support and moving equipment or messages among units. And who better to instruct soldiers on that than 1st Lt. John Harley — son of William Harley, of Harley-Davidson fame. 1st Lt. Harley was still “very much a motorcycle enthusiast,” Cogan said, so in his free time at Fort Knox, he would tinker with the bikes to show soldiers what to remove or modify to make them go faster.

Fast forward a few years at the end of the war, and soldiers had found a match made in Heaven: they had some money in their pockets, and the motorcycles that were used by the cavalry were being “sold for dirt cheap,” Cogan said. But the motorcycles also had a number of things your average rider doesn’t need — various racks and things for storage that the Army wanted, but that weren’t really necessary for civilian use.

“They didn’t care about having a blackout light that you’d use in tactical situations, they didn’t care about the rifle rack, so they chopped some of those off and that’s where you get the term ‘American Chopper’ coming from because of these modified Army motorcycles,” he said. “So really World War II and the U.S. mechanized cavalry that really creates the American motorcycle culture today.”

It didn’t take long for the civilian world to catch on to this trend of “chopping” and modifying motorcycles for style and speed. Whether for looks or drag racing, the style caught on with riders across the country in the 1950s and 1960s, ultimately becoming a countercultural icon in its own right.

Harley-Davidson was later awarded two Army-Navy “E” Awards for Excellence in Production during World War II. And while the military has come a long way since then, Cogan said it stands as a reminder of the way military and civilian culture have intertwined in the past.

“The military culture in our society — it permeates more than you think,” he said.

The latest on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.