Editor’s note: This story first appeared in August 2019

Early in the morning of August 6, 1945, a U.S. Air Force B29 bomber, the Enola Gay, took off from the its base in Tinian, near Guam, and headed for the city of Hiroshima in southern Japan.

It was carrying a 9,700 top-secret bomb named Little Boy. Its pilot was Col. Paul W. Tibbets Jr., who led a crew of 12 men on a mission that would change the history of the world.

The plane had been named by Tibbets after his mother.

Hiroshima had already been woken by several air raid sirens that morning, which had proven to be false alarms.

So when Enola Gay approached at 8.15 am, many thought it was a reconnaissance plane. By the time the siren sounded, the first atom bomb had already dropped.

In a blinding flash, and with temperatures as hot as the sun, the bomb detonated. It destroyed a five-mile radius, killing 80,000 people.

Tens of thousands more later died of radiation sickness and injuries.

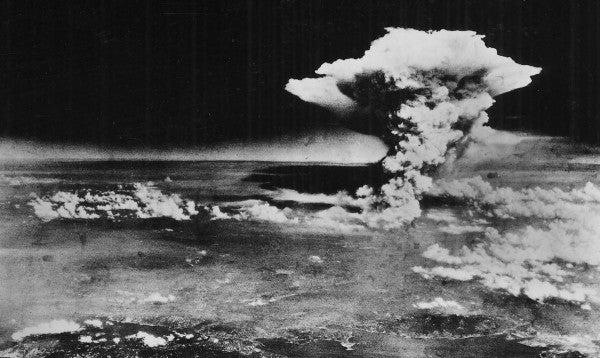

In this Aug. 6, 1945, photo released by the U.S. Army, a huge cloud resulting from the massive fires started by “Little Boy”, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, is photographed from a reconnaissance plane a few hours after the initial explosion

(Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum/U.S. Army via Associated Press)

The Enola Gay was 10 miles away when the blast went off, but still felt the shockwaves. The crew recalled the jolt from the force of the explosion, and said it was like coming under enemy fire.

Three days later the second atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki and Japan surrendered, bringing World War II to an end.

Debate has raged ever since over whether the U.S. was right to launch the attacks. Some have argued that the bombing was an inhumane targeting of civilians, and there were other options available.

But how did the explosion weigh with the 12 men aboard the Enola Gay who dropped the bomb that day?

Then-Col. Paul W. Tibbets (center) with six of the aircraft’s crew (three on each side) in an undated photo(U.S. Air Force via Wikimedia Commons)

Pilot Tibbetts Jr and other crew members believed to the end of their lives that the bomb was necessary — and they say that it ultimately saved lives.

In a 2002 interview, Tibbetts told writer Studs Terkel: “I knew we did the right thing because when I knew we’d be doing that I thought, yes, we’re going to kill a lot of people, but by God we’re going to save a lot of lives. We won’t have to invade [Japan].”

The U.S. military had calculated that an invasion of Japan could have cost millions of U.S. and Japanese lives. So the reasoning goes, the attacks were necessary as an overwhelming show of force to stop the war dragging on further.

As for the loss of civilian lives, Tibbets was unrepentant.

He said: “You’re gonna kill innocent people at the same time, but we’ve never fought a damn war anywhere in the world where they didn’t kill innocent people.

“If the newspapers would just cut out the s–t: ‘You’ve killed so many civilians.’ That’s their tough luck for being there,” he said.

Then-Brigadier General Paul W. Tibbets, Jr.(U.S. Air Force photo)

Some of the members later came to express regret, and were haunted by the destruction they caused.

Captain Theodore van Kirk, the plane’s navigator that day, said in a 2005 interview: “I pray no man will have to witness that sight again. Such a terrible waste, such a loss of life.

“We unleashed the first atomic bomb, and I hope there will never be another. I pray that we have learned a lesson for all time. But I’m not sure that we have.”

To date, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the only places which have been targeted by a nuclear bomb in war.

In recent years though Cold War treaties halting the proliferation of nuclear weapons have begun to unravel, lending fresh urgency to questions on the morality of nuclear conflict.

Read more from Business Insider: