Editor’s note: This story contains detailed descriptions of violence that occurred during the August 2021 withdrawal mission in Afghanistan.

Sgt. Ben Johnson was standing outside the main terminal of the Hamid Karzai International Airport (HKIA) in Kabul when the two young Afghan women approached. He immediately noticed how beautiful they were, and in near-perfect English, they asked him to let them through.

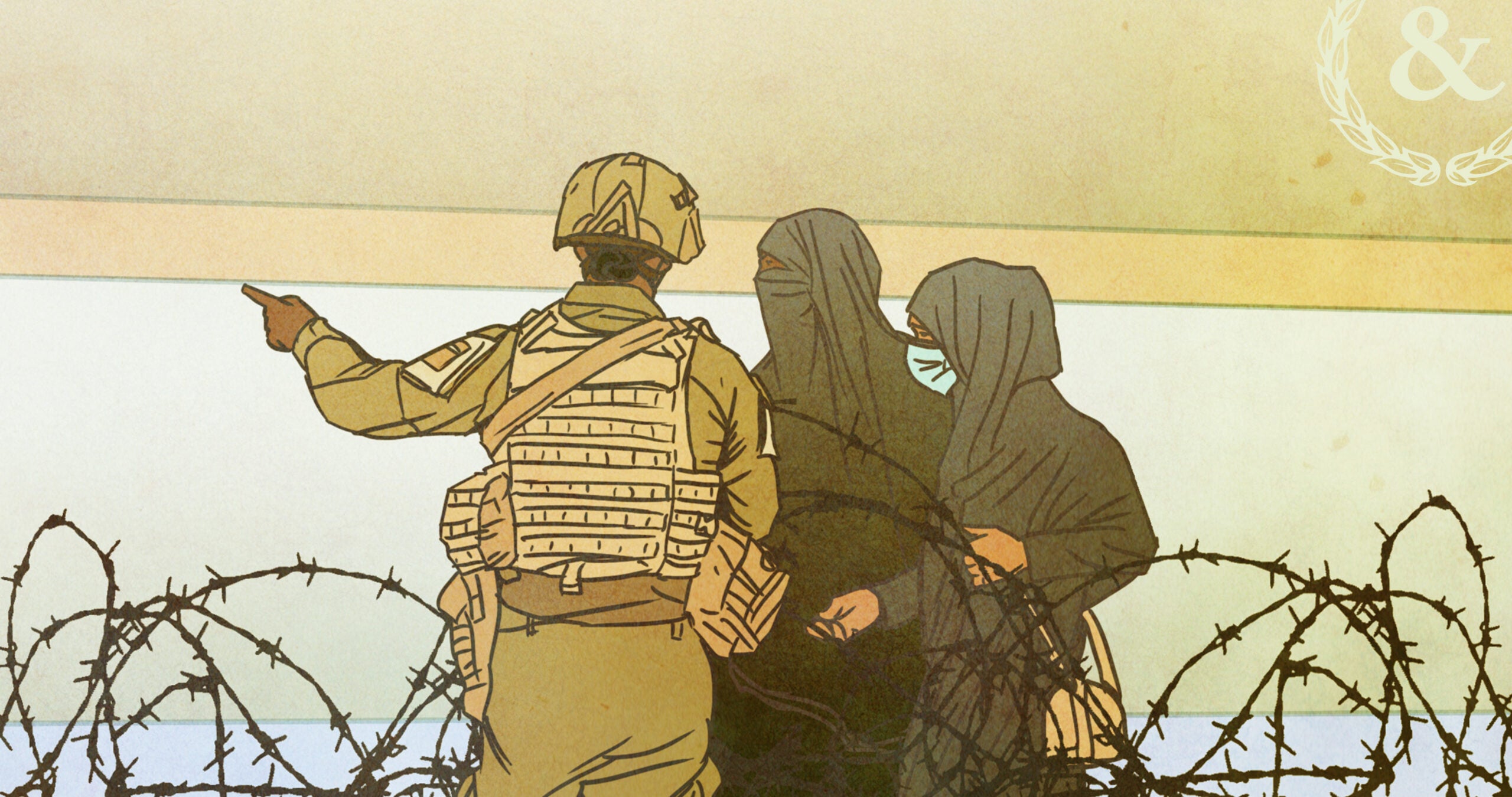

It was days into the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, and Johnson — a soldier who deployed with the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division and is being identified by a pseudonym by Task & Purpose at his request — was tasked with moving concertina wire for military vehicles driving into the airport. The women, who he estimated to be somewhere between 17 and 21 years old, were just two of thousands with the same dire request: Please, save us. He explained to the women that he couldn’t let them in. If he did, he’d have to let everyone else through, too. He told them to go to the South Gate. If they had a chance of getting in anywhere, it was there.

“They were like, ‘They won’t let us go back that way. They’ll kill us,” Johnson recalled them saying of the Taliban, who were standing just feet away.

“I didn’t want the Taliban to do anything to them, but then they also couldn’t get through my gate,” he said. “So I finally get them out and I’m yelling at the Taliban, like take these girls out of here. And they go behind the wall and kill them.”

It wasn’t the last time he would witness the Taliban execute someone for getting in their way, causing trouble, or for no apparent reason at all. But there wasn’t much he could do. The Taliban had taken over Kabul and by extension, control of Afghanistan. And as the U.S. and its allies worked around the clock to evacuate civilians from the country, they’d entered into a tense agreement of sorts with the Taliban to ensure safe passage to HKIA for those attempting to leave. The U.S. and its allies would control the airport while the Taliban was controlling checkpoints on the roads leading to its gates.

When the two women were killed, Johnson recalled that his platoon sergeant — who he called the best leader he’s served under in the military — told him it would be okay to go sit down for a moment.

“I didn’t want to,” Johnson said. “Because then I knew I would have time to process and register what just happened. I was like no, I’m going to stay busy. I can deal with emotions and thoughts when this is all over with.”

That mindset was common among other service members deployed to HKIA last August. While they were working to make sense of the chaos, those who spoke to Task & Purpose described an awareness that they simply did not have time to think about what they were seeing and witnessing. They would process it all later.

A year later, many of them still are. And many of them say that recognition for the many acts of valor committed there, or even acknowledgment of the reality of that mission from the military, the government and the public, have all been hard to come by.

This story is based on official documents, remarks from senior leaders, and hours of interviews with 15 soldiers, airmen, and Marines who were directly involved in the evacuation of tens of thousands of people during the Afghanistan withdrawal mission. Many of them spoke on condition of anonymity in order to talk candidly, without fear of reprisal or being ostracized for sharing details about their mental health. While their experiences differed based on where they were and what they were doing during those two weeks, there were common threads throughout their stories: They felt the military wanted to move on as quickly and quietly as possible from the withdrawal. Many said their commands brushed the trauma they brought home with them under the rug and were slow-rolling awards and recognition for the mission, for reasons they didn’t understand.

They also described a sort of emotional tug-of-war: they’re proud of having helped the people they could but angry over the lack of accountability for a mission that placed them in such an impossible situation. And as the rest of the world has seemingly moved on, and the Afghanistan withdrawal is relegated to once-a-year news specials, many of those who witnessed the chaos first-hand are still finding their way back.

In a way, the withdrawal mission — a noncombatant evacuation operation — was both incredibly unique and painfully predictable. It was unlike anything troops on the ground had experienced before. Even those who had deployment experience to Afghanistan said it felt impossible to have adequately prepared for what they were there to do. But the mission ultimately ended the way so many others had before it: When it was all said and done, the institution failed to care for the very people it depended on to get the mission done.

Brig. Gen. Patrick Ryder, a spokesman for the Department of Defense, told Task & Purpose that Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin remains “in awe of the incredible work our brave service members accomplished under extreme conditions during the closing weeks of the U.S. presence in Afghanistan.”

“This accomplishment was unfortunately earned at the highest of prices with the loss of 13 of our courageous service members during the attack at Abbey Gate – 11 Marines, a soldier, and a sailor,” Ryder said. He added that the mental health and well-being of service members “remains a top priority,” and encouraged troops and their families to seek help for “the wounds of war — whether visible or invisible.”

After coming home, some service members who spoke to Task & Purpose described difficulties being in large crowds and hearing children cry in public, which sometimes brought on anxiety attacks after they first returned. Some said they feel like they haven’t had a full night’s sleep since August 2021. One said he still sees the faces of those he couldn’t help, every single morning upon waking up. Another said he relates everything back to that deployment, despite his best efforts not to.

“I feel like I’m still there,” one radio operator with 1st Marine Division said. “I feel like everything that happened, happened five minutes ago, not 11 months ago.”

And that’s to say nothing of the lasting impact of losing 13 service members in a suicide bombing at Abbey Gate on Aug. 26. Chris Rodriguez, a Marine with 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Division, who is being identified by a pseudonym, recounted that he was not at Abbey Gate when the bomb went off. But because he was higher ranking than some of those who died, he felt it should have been him, that he should have been standing in someone’s place when the bomb detonated.

“I felt like that was my job,” Rodriguez said matter-of-factly. “I feel guilty about that a lot. Like I don’t deserve to be here.” He added that he’s “accepted there is no help,” and that the higher-ups “don’t give one shit about us.”

Luke Matthews, a Marine forward observer who was attached to 1st Battalion, 8th Marines during the withdrawal, and who is also being identified by a pseudonym, said that he has feelings of depression and regret. Some days, he said, he wakes up angry and doesn’t know why. But he also believes the troops on the ground did the best they could with the situation they were handed.

“We got there and we got dealt a shitty hand,” Matthews said. “And we just did what we had to do. So I don’t think we did anything wrong. But I do think that the leadership from probably the battalion level, all the way up to the Pentagon and the White House, fucked us.”

‘This is absolutely crazy’

It has been well-established that for the troops deployed last August, the rulebook more or less went out the window.

Soldiers and Marines were hot-wiring and commandeering vehicles — including a fire truck, in one instance, which one soldier called “funny as hell” — to get around the airport. Some Army paratroopers traded cans of dip for a Toyota Land Cruiser outfitted with an anti-aircraft gun, showcasing the ingenuity of the American soldier. Army 1st Sgt. Eamonn McDonough, the operations sergeant for the 23rd Military Police Company at Fort Drum, New York, acknowledged that hot-wiring vehicles isn’t exactly something law enforcement would typically condone, but in this instance, it was just about getting the job done. He laughed that when they got home, they explained to their soldiers they “can’t do that anymore.”

“I’ve never been in that situation,” said an Air Force aerial transportation specialist who is being identified as Nate Perrino, “where you have the wildest, most irresponsible fun you’ve ever had in your life, and the most emotionally traumatic thing you’ve ever dealt with, within 15 minutes of each other.”

Similar dichotomies existed throughout the mission, one of the biggest being the tenuous agreement the U.S. held with the Taliban throughout the evacuation. After 20 years of fighting, senior U.S. officials back in Washington, D.C. were declaring that the Taliban was prepared to offer safe passage to the airport for civilians attempting to leave the country. But anyone on the ground could tell you it wasn’t quite that easy.

The Taliban were somewhat helpful with aspects of the evacuation, in some regards. One soldier said when civilians swarmed the airfield — which multiple service members compared to apocalyptic-looking scenes from the movie World War Z — it felt nearly impossible to get control of the situation. People were trampling one another, including children who’d fallen down. No one was listening or taking direction. And soon the world watched as desperate Afghans clung to the sides of an Air Force C-17 Globemaster II, only to fall to their deaths moments later as the plane took off.

It was “full-on mob mentality,” said Army Spc. Martin, a soldier whose identity is being withheld as he is still serving and who deployed to HKIA with the 504th Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division.

And while no one wanted to involve the Taliban, retired Gen. Frank McKenzie, the head of U.S. Central Command at the time of the withdrawal, told Politico that doing so “let the commander on the ground regain control of the airfield.”

“We had 400 Taliban fighters beating people with sticks,” he said. “It’s not what you want, but you’re in the land of bad choices now.”

That strained partnership continued until the very end. “I’m working with the Taliban, who shot me in 2009,” one senior Marine noncommissioned officer recalled thinking. “This is absolutely crazy.”

But even then, the Taliban’s brutality was on full display. Soldiers and Marines recalled sitting at the gates of the airport with Taliban fighters just steps away, at times pointing their weapons at American and allied forces, watching and waiting. Johnson, who witnessed two women get executed after sending them away, said the Taliban did the same to one of their own who had fallen asleep in a rolling chair and “accidentally pulled the trigger” of his weapon.

“It went straight into the ground, but they pulled him behind the wall and they killed him,” Johnson said. “And that’s literally how that went. If somebody messed up, they killed them. If somebody did something wrong, they killed them.”

Matthews was working an exit near the North Gate when he learned the Taliban was executing anyone who was sent back outside the airport. While he and the other Marines at the gate heard gunshots down the road, they didn’t find it unusual. They were in Afghanistan, after all, and the Taliban were everywhere. But a sniper providing overwatch of North Gate later asked if Matthews and the other Marines knew what was going on, and explained that they’d seen the Taliban take whoever was sent out the exit gate, drag them down the road, force them on their knees, and shoot them with a pistol.

It’s all Matthews said he and one of his buddies thought about after a family of four, a man and three little girls ranging in age from one to five years old, were told to leave. The man was taking off his boots after walking into the gate, Matthews said, when someone higher ranking demanded to know what he was doing and told them to get him out of the airport.

“That’s something that me and my buddies will never forget … Three little girls. God knows what happened to them,” he said.

The soldiers and Marines at the airport described one horror after another, born from unbridled desperation among the people hoping to escape Taliban rule. Women and children were trampled, they said; men sometimes opted to leave their families behind if they didn’t have the right paperwork. People pushed one another into concertina wire as they crowded towards a gate entrance. One Marine described seeing “children used as blankets” on the wire, being thrown on top of it in a (futile) effort to get the whole family into the airport. The same Marine also recalled being at the North Gate when he was handed a little girl who was having a health emergency. He was looking for a Corpsman, he said, when she died in his arms.

It got even worse on Aug. 26, when a suicide bomber approached Abbey Gate and detonated a single explosive device, killing 13 U.S. service members and more than 150 civilians. While initial reports said the bombing was a “complex attack” that included an explosive and gunmen, a subsequent investigation found that the one explosive device fired ball bearings when it detonated, which caused wounds that looked like gunshots.

Rodriguez was taking a child to the makeshift hospital at the airport when the bomb exploded. When he heard what happened he immediately rushed back to the gate. All he remembers from the following moments are flashes of memories: a woman laying on the ground and a little girl standing over her, covered in blood. Injured Marines receiving medical treatment. “Piles of bodies” in the canal outside the gate. A woman sitting on the ground, screaming.

That trauma was acknowledged in the official investigation of the Abbey Gate bombing, which was released in February this year.

“During the response to the attack at Abbey Gate, young Marines heroically recovered the wounded and rendered life-saving care. Others carried the bodies of their deceased friends away from the canal,” investigators said in the report. “In consideration of the mental and emotional strain placed on these young Marines and other service members, I recommend … mental health evaluations and treatment options for all personnel executing entry control point operations at Abbey Gate from 17-26 August.”

Yet the support those troops received upon coming home seems to have varied wildly, and in the eyes of some of those service members, it seems to come down to whether their leaders cared to make it a priority or not. One soldier recalled chaplains coming out to speak to soldiers who deployed as they waited in Kuwait to get back to the U.S., though soldiers also said the actual evaluation they received was the same they get after any deployment or training exercise. A couple of Marines said that their immediate leadership talked with them, and assured them it was okay to seek help. One C-17 pilot said their leadership “did what they could” to get their airmen resources.

Lt. Gen. Christopher Donahue, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division at the time of the withdrawal, said in a statement to Task & Purpose that “prior to redeployment, all TF-82 Service Members were screened by behavioral health professionals from the most junior paratrooper to the commanding general, to ensure that our soldiers received the proper care they deserve.”

“We will always demonstrate the courage to act when our people need help,” Donahue said.

But still, many service members said that it has been extremely difficult to get the care they needed since returning home, either because of a lack of available behavioral health appointments or leaders who don’t prioritize it.

Johnson, who is stationed at Fort Bragg, said that if he went to behavioral health and “told them ‘I’m really struggling, I can’t sleep, I feel super depressed, I’m just not in a good spot and I really need to talk to somebody,’ they’ll give me an appointment three weeks from now. At least three weeks.”

The senior Marine NCO echoed the same. The deployment to HKIA was his seventh, he said, and hands-down his worst, despite the astonishing selflessness and bravery he said his Marines displayed. A few months after returning, he went to behavioral health and told them what he thought would be immediate red flags — that he was drinking a lot, and had thoughts of hurting himself.

“Those are the two things that I’ve seen in my Marine Corps career that are red flags that you get fucking immediate help for,” he said. “This was … the first week of November. And the two fucking Navy people at the desk go, ‘Uh, our next appointment is the 23rd. Can you come in the 23rd?’ I go are you fucking kidding me? You’re going to do me like that? You guys tell us all, ‘Get help, get help, get help.’ And then you fucking tell me three weeks out? I just told you I’m fucking drowning myself in alcohol and I want to fucking off myself, and that’s your reply?”

Capt. Ryan Bruce, a Marine Corps spokesman, told Task & Purpose the service “requires our deployers to complete deployment health assessments, which include mental health assessments.” He added there are “multiple opportunities” for this: “before deployment, during deployment, upon leaving theater, 3-6 months after return to home station, and 1- and 2-years after return.”

Among those service members who spoke to Task & Purpose, some raised concerns that most people, even other service members, don’t realize exactly what happened at HKIA during those 17 days. “The depth of the absolute chaos” on the ground hasn’t been conveyed well enough, Perrino said. The enormity of the mission and what those service members accomplished has “never been fully communicated,” said a C-17 pilot.

A year later, that hasn’t changed. Some said they have found help outside the military. Others are leaning on each other, finding it therapeutic to talk to fellow soldiers, airmen, or Marines who deployed with them. Martin said if it came down to it and his fellow soldiers were called to go back, “I would go in a heartbeat.”

Ultimately, the senior Marine NCO said he was able to get the help he needed through the military. And while it’s been a long road, he’s finally on the other side of it.

“Last month was the first month I started feeling good,” he said.

‘The lies finally caught up’

Announcements of military awards and decorations for those involved in the Afghanistan withdrawal have slowly trickled out over the last year.

An Air Force captain who coordinated the historic airlift at HKIA was awarded the Bronze Star in January. And in April, four airmen received the Distinguished Flying Cross for completing the first evacuation flight. Just recently, a Marine sergeant was awarded the Bronze Star with “V” device for valor, for saving another Marine’s life during the suicide bombing on Aug. 26. And this month, roughly a dozen soldiers with the 82nd Airborne Division were awarded Air Medals with “C” or “V” devices. In total, more than 50 soldiers who deployed with the combat aviation brigade will receive the medals.

But other service members raised a number of concerns with the way the military is handling awards and badges, including that they are being slow-rolled for reasons they don’t understand, flat-out denied, or downgraded because of rank.

Martin said that while brigade leaders are getting awards, the soldiers who deployed have been waiting to get combat badges. When they asked a senior enlisted leader if they’d receive them, he “basically told us that we don’t deserve them, because compared to people that have served before us, like in Vietnam, we didn’t do shit,” Martin said.

Capt. Matt Visser, a spokesman for the 18th Airborne Corps, said 300 soldiers who deployed on the mission have received the combat action badge, combat infantryman badge, or combat medical badge. Bruce, the Marine Corps spokesman, said the “overall process” for personal and unit decorations is “ongoing,” and that the review and approval process is “by necessity, detailed and thorough, which takes time.”

Perrino and a C-17 pilot both said it’s an unspoken rule in the service that lower-ranking service members won’t be eligible for certain awards simply because of their rank.

“There are hundreds of decorations for the operation that have been sent to AFCENT for approval, months ago, and we don’t know if and when we will ever see any type of recognition for the crews or the personnel that helped make [Operations Allies Refuge] happen,” the pilot said.

It all comes back to the idea that what actually happened isn’t clear enough, he said. The people reviewing the awards for approval don’t get it.

“It’s hard to describe,” the pilot added, “sitting on the ground at Kabul and watching the tracer fires in the air, and watching aircraft taxiing around, dodging vehicles and loading these refugees under the dark of night and flying out again. Every jet that took off, another jet landed. The enormity of the operation, I just don’t think the people who look at these decorations and view them, grasp what actually occurred. And I don’t know why.”

Ann Stefanek, an Air Force spokeswoman, confirmed there are “hundreds of awards submissions” still being processed by the service, which has been delayed because of “the high number of award submissions coupled with the expiration of the Air Force Central Command commander’s approval authority.”

“AFCENT recently received an extension authorizing continued processing of those decorations and will begin working through the backlog,” Stefanek said. “The next AFCENT Board is scheduled for mid-September and will review pending award nominations.”

And really, it’s not even about the medals or badges. The soldiers, airmen, and Marines who spoke to Task & Purpose said it’s about acknowledging what happened. It’s about acknowledging what was accomplished in those few days under such chaotic and violent circumstances and recognizing the situation for what it was.

But many also said they never expect to see that kind of honesty from the top officials who put them there in the first place. After all, Perrino said, the entirety of the Afghanistan War was plagued with lies and glossed-over realities from commanders and senior officials. Given the war’s history, why should its end be any different? As confidential documents published by the Washington Post in 2019 revealed, senior U.S. military leaders knew for years the war in Afghanistan was unwinnable, yet continued to make public statements to the contrary.

“It’s like I tell my kids if they’re lying about something, then another lie, and you have to lie again, and then you’ve got to keep all your lies straight. And I think with the Afghan pull-out, for years we’d just been lying to ourselves about the situation in Afghanistan,” he said. “The lies finally caught up.”

At the end of each interview with the service members who spoke for this article, they were asked if there was anything they hadn’t already discussed that they wanted to add, or anything they wanted people to keep in mind as this one-year anniversary came and went. Many took the opportunity to encourage others who deployed to reach out to one another and check-in.

One of the Marines said anyone who calls the military “soft” can “go screw themselves” because “I watched a bunch of teenagers … do some pretty hardcore shit.” More than one person called for accountability from the senior defense and government officials who oversaw the withdrawal — or at least for them to be held as accountable as a soldier who loses a piece of equipment.

But Perrino offered his final thoughts in a simple sentence: “I hope we don’t do this again.”

Service members and their families seeking mental health support can visit MilitaryOneSource, call the Military Crisis Line at 800-273-8255, dial 9-8-8 (short code), then press 1, or access online chat by texting 838255.

The latest on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.