The Star Wars universe is famous for barrel-rolling, laser-blasting dogfights between starfighters. That’s fine for space battles, but what about the dog-faced Imperial stormtroopers and rebel infantry grunts slogging it out in the muddy soil of hostile worlds?

The Air Force A-10 Thunderbolt II, also known as the Warthog, is a massive fan favorite, particularly among ground combat personnel. The aircraft was designed specifically for destroying enemy tanks and supporting troops on the ground against nearby threats. We have written extensively about how difficult the aircraft is to kill and how much easier it makes life for U.S. grunts. But is there anything like the Warthog in Star Wars, the science fiction universe that so many U.S. service members love?

At least one former A-10 pilot has thought long and hard about this question, and his answer is convincing. Turns out, the closest thing to a Warthog in the Star Wars universe is not the iconic T-65B X-Wing or TIE star fighters, or their slower cousins, the Y-Wing and TIE bombers. Instead, it’s a humble aircraft that can’t jump to hyperspace or even leave the atmosphere: the squat Incom T-47 air speeder, more commonly known as the snow speeder.

“I love the snow speeders that attacked the AT-ATs in Episode V,” said retired Air Force Lt. Col. Gregg Montijo. “They always reminded me of an A-10, albeit with two people [in the cockpit].”

The snow speeders made their debut in the second Star Wars movie to be released, The Empire Strikes Back. The snow speeders help the Rebel Alliance mount a desperate defense against the invading Imperial army on the ice planet Hoth. While the tiny two-person speeders are fast and maneuverable, their twin laser cannons can’t penetrate the thick armor of the four-legged Imperial All Terrain Armored Transports (AT-ATs). Instead, the lead pilot, Luke Skywalker, tells his comrades to shoot the speeder’s rear-facing harpoon at the walkers’ legs, then spin out the attached tow cable as the pilot circles the walker. The cable wraps around the AT-AT’s legs, making the massive walker trip into the snow, delaying the Imperial advance while the rebels evacuate the planet.

[embedded content]

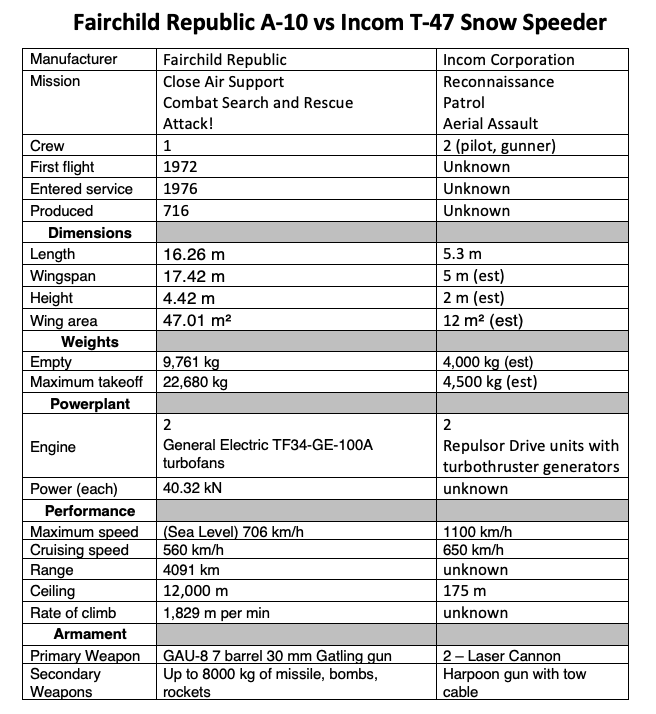

The scene is one of the rare instances of close air support in the Star Wars movies, and Montijo spotted plenty of similarities between the snow speeder and the A-10 he spent his career flying.

“They both flew low altitude (in the weeds/snow) just like the A-10 practiced during the Cold War days,” Montijo said. “Both have rather blunt front noses, both have big flat plate windscreen up front, they each have primary large ‘cannons,’ both are twin engined.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

The similarities go even deeper than that. The retired A-10 pilot pointed out that both the Warthog and the snow speeder have large speed brakes to rapidly slow down, both have very tight turn radii, both have short takeoff and landing capabilities (in fact, the snow speeder can take off and land vertically, while the A-10 can land on a dirt airstrip), both can operate in austere conditions (like an ice planet), and both were cobbled together on the cheap.

Built by the same sci-fi aerospace company which made the X-Wing star fighter, the T-47 air speeder was originally designed for industrial cargo transport, according to toy maker Lego. But when the Rebel Alliance fled to Hoth to escape the Empire, its crafty technicians converted the hauler into a light, fast patrol and combat speeder.

“The glacial weather on Hoth also forced the Rebel Alliance to adapt the snow speeder to function in frigid temperatures for extended lengths of time,” Lego explained. “Heaters were added near the drive units, de-icing nozzles were added to prevent ice forming on control surfaces, and Rebel technicians also used scavenged Y-wing parts, armor plates, and refitted cockpit modules to further improve the design and defense capabilities.”

Likewise, while the A-10 airframe was original, all the systems on it were installed “off the shelf” from other aircraft, Montijo explained. The twin jet engines came the Navy’s S-3 Viking multi-role aircraft; its auxiliary power unit came from the C-130 transport plane; its throttles from an F-15A fighter; its main landing gear from the nose tire of a C-141 transport jet; its ejection seat from the F-15A and B-1 bomber, its internal navigation and radar altimeter from the B-52 bomber, and a ton of other instruments, bits and bobs cobbled together from existing aircraft.

Part of why the A-10 was stitched together was because it had to be developed on the cheap. According to the 2002 book Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, by Robert Coram, the Air Force wanted to keep the close air support mission but only if it cost less than the proposed Cheyenne helicopter the Army was developing to take it over.

“Usually there are no cost constraints on an aircraft-design program. Politically there are often many reasons to maximize costs,” Coram wrote. “In all the history of the Air Force, the A-X [later the A-10] was the single exception. It had to be cheap. It had to cost less than the Cheyenne.”

The economical design molded by the engineer Pierre Sprey eventually paid off for troops under fire and earned the aircraft a reputation as a tank-buster. Busting real-life tanks is all well and good, but the most important question remains: how would an A-10 fare against the armored hide of an AT-AT walker? Many service members have pondered this question, but few are better equipped to answer it than Montijo.

“I think the A-10 with the depleted uranium rounds would be effective against an AT-AT and other similar equipment provided they do not have any force fields protecting them,” the pilot said.

The depleted uranium rounds fired by an A-10 are truly terrifying, with the ability to turn enemy armor into white-hot chunks of shrapnel flying around inside a troop or crew compartment. The A-10 could fire its legendary GAU-8 cannon at the AT-AT’s head or body, or at its vulnerable neck and feet, as one Army veteran suggested. But Montijo said he thought the best bet would be to stay low and attack the body or leg area, or to shoot up at the belly.

“When the A-10 would attack tanks, the most thinly-armored part of the tank was the top and the engine,” he explained. “Attacking an AT-AT from the top might put the A-10 in a vulnerable position and much more exposed to laser cannon fire.”

Now the fun question: could an A-10 turn like a snow speeder in order to bring down an AT-AT with a tow cable? While the Warthog could no doubt maneuver to attach a tow cable to the walker (assuming someone could figure out how to mount a cable launcher to the aircraft to begin with), turning in time would be more tricky, Montijo said.

“As for maneuvering – the A-10 could maneuver around the legs of the AT-AT, but it would be way wider than a snow speeder and might not have enough cable,” he explained.

The minimum turning radius for an A-10 is about 1,500 feet, if the pilot can sustain that at about 7.2 times the force of gravity, which would be generated by such a tight turn. In total, that would make for a 3,000 foot diameter circle, “which might be a bit too large to bring down an AT-AT,” he said.

Who knows, with its ability to carry up to 16,000 pounds of ordnance beneath its wings and fuselage, the Warthog may be able to lug enough cable to do the trick. But it might be more efficient to just bring a bunch of weapons, like 500 pound Mk-82 bombs or AGM-65 Maverick missiles. All in all, if you are an Imperial AT-AT driver and you see a Warthog over the horizon, you’re probably gonna have a bad time.

Both the A-10 and the snow speeder sport armor plating to ward off enemy fire. Unfortunately, we see many snow speeders go down after a single hit from an AT-AT in The Empire Strikes Back, but perhaps the AT-AT’s laser cannons fire an unstoppably heavy caliber of laser beam, or however that works. At the end of the day, the humble snow speeder and the legendary Warthog bear a lot in common. Most importantly, they swoop in to help the people in most urgent danger: the grunts on the ground.

“Each has similar missions,” Montijo said, “support the troops.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.