NUSA DUA, Indonesia (AP) — President Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping opened their first in-person meeting Monday since the U.S. president took office nearly two years ago, amid increasing economic and security tensions between the two superpowers as they compete for global influence.

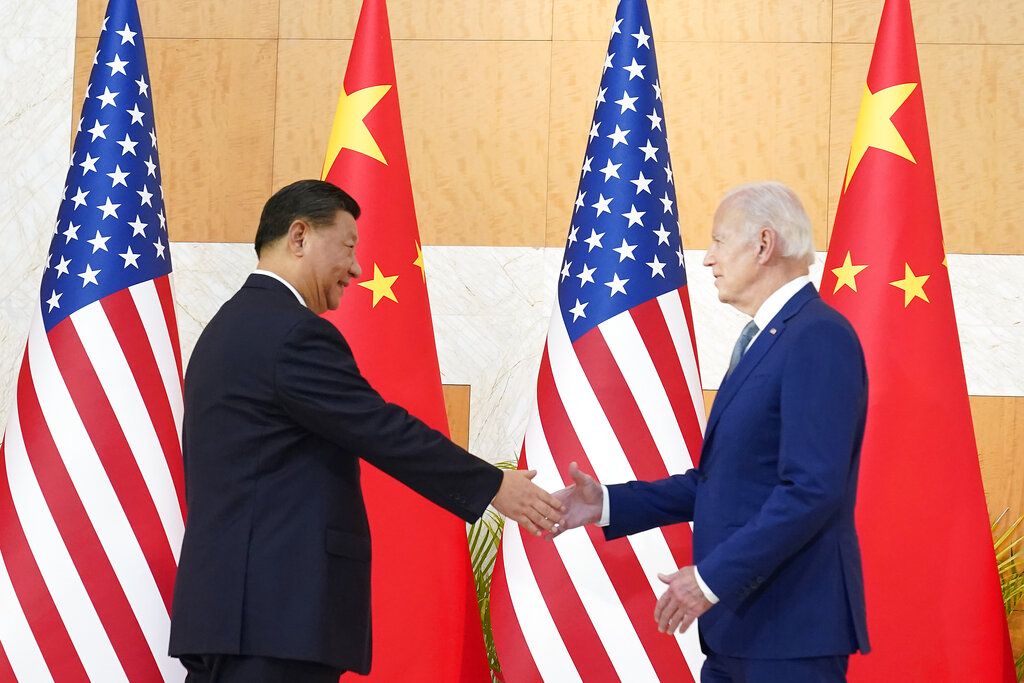

Xi and Biden greeted each other with a handshake at a luxury resort hotel in Indonesia, where they are attending the Group of 20 summit of large economies. U.S. officials say Biden aims to “build a floor” in the relationship between the leaders — and nations — to identify areas of potential cooperation and to avoid miscalculations between the nuclear powers on areas of disagreement.

Both men entered the highly anticipated meeting with bolstered political standing at home. Democrats triumphantly held onto control of the U.S. Senate, with a chance to boost their ranks by one in a runoff election in Georgia next month, while Xi was awarded a third five-year term in October by the Communist Party’s national congress, a break with tradition.

“We have very little misunderstanding,” Biden told reporters in Phnom Penh, Cambodia on Sunday, where he participated in a gathering of southeast Asian nations before leaving for Indonesia. “We just got to figure out where the red lines are and … what are the most important things to each of us going into the next two years.”

Biden added: “His circumstance has changed, to state the obvious, at home.” The president said of his own situation: “I know I’m coming in stronger.”

White House aides have repeatedly sought to play down any notion of conflict between the two nations and have emphasized that they believe the two countries can work in tandem on shared challenges such as climate change and health security.

But relations between the U.S. and China have grown more strained under successive American administrations, as economic, trade, human rights and security differences have come to the fore.

As president, Biden has repeatedly taken China to task for human rights abuses against the Uyghur people and other ethnic minorities, crackdowns on democracy activists in Hong Kong, coercive trade practices, military provocations against self-ruled Taiwan and differences over Russia’s prosecution of its war against Ukraine. Chinese officials have largely refrained from public criticism of Russia’s war, although Beijing has avoided direct support such as supplying arms.

Taiwan has emerged as one of the most contentious issues between Washington and Beijing. Multiple times in his presidency, Biden has said the U.S. would defend the island — which China has eyed for eventual unification — in case of a Beijing-led invasion. But administration officials have stressed each time that the U.S.’s “One China” policy has not changed. That policy recognizes the government in Beijing while allowing for informal relations and defense ties with Taipei, and its posture of “strategic ambiguity” over whether whether it would respond militarily if the were island attacked.

Tensions flared even higher when House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., visited Taiwan in August, prompting China to retaliate with military drills and the firing of ballistic missiles into nearby waters.

The Biden administration also blocked exports of advanced computer chips to China last month — a national security move that bolsters U.S. competition against Beijing. Chinese officials quickly condemned the restrictions.

And though the two men have held five phone or video calls during Biden’s presidency, White House officials say those encounters are no substitute for Biden being able to meet and size up Xi in person. That task is all the more important after Xi strengthened his grip on power through the party congress, as lower-level Chinese officials have been unable or unwilling to speak for their leader.

Asked about the anticipated meeting, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said last week at a news briefing that China was looking for “win-win cooperation with the U.S.” while reiterating Beijing’s concerns about the U.S. stance on Taiwan.

“The U.S. needs to stop obscuring, hollowing out and distorting the One China principle, abide by the basic norms in international relations, including respecting other countries’ sovereignty, territorial integrity and noninterference in other countries’ internal affairs,” he said.

Xi has stayed close to home throughout the global COVID-19 pandemic, where he has enforced a “zero-COVID” policy that has resulted in mass lockdowns that have roiled the global supply chains.

He made his first trip outside China since start of the pandemic in September with a stop in Kazakhstan and then onto Uzbekistan to take part in the eight-nation Shanghai Cooperation Organization with Putin and other leaders of the Central Asian security group.

White House officials and their Chinese counterparts have spent weeks negotiating out all of the details of the meeting, which is taking place at Xi’s hotel with translators providing simultaneous interpretation through headsets.

U.S. officials were eager to see how Xi approaches the Biden sit-down after consolidating his position as the unquestioned leader of the state, saying they would wait to assess whether that made him more or less likely to seek out areas of cooperation with the U.S.

Biden and Xi each brought small delegations into the discussion, with U.S. officials expecting that Xi would bring newly-elevated government officials to the sit-down and expressing hope that it could lead to more substantive engagements down the line.

Before meeting with Xi, Biden first held a sit-down with Indonesian President Joko Widodo, who is hosting the G-20 summit, to announce a range of new development initiatives for the archipelago nation, including investments in climate, security, and education.

Many of Biden’s conversations and engagements during his three-country tour — which took him to Egypt and Cambodia before he landed on the island of Bali on Sunday — were, by design, preparing him for his meeting with Xi and sending a signal that the U.S. would compete in areas where Xi has also worked to expand his country’s influence.

In Phnom Penh, Biden sought to assert U.S. influence and commitment in a region where China has also been making inroads and where many nations feel allied with Beijing. He also sought input on what he should raise with Xi in conversations with leaders from Japan, South Korea and Australia.

The two men have a history that dates to Biden’s time as vice president, when he embarked on a get-to-know-you mission with Xi, then China’s vice president, in travels that brought Xi to Washington and Biden through travels on the Tibetan plateau. The U.S. president has emphasized that he knows Xi well and he wants to use this in-person meeting to better understand where the two men stand.

Biden was fond of tucking references to his conversations with Xi into his travels around the U.S. ahead of the midterm elections, using the Chinese leader’s preference for autocratic governance to make his own case to voters why democracy should prevail.

The president’s view was somewhat validated on the global stage, as White House aides said several world leaders approached Biden during his time in Cambodia — where he was meeting with Asian allies to reassure them of the U.S. commitment to the region in the face of China’s assertive actions — to tell him they watched the outcome of the midterm elections closely and that the results were a triumph for democracy.

U.S. officials said no joint communique was expected after the meeting with Xi and downplayed expectations for policy breakthroughs. The White House said Biden planned to hold a press after his meeting with Xi.

—

AP writer Josh Boak in Washington contributed.