Early last year, Scott Stephenson, president and CEO of the Museum of the American Revolution, received a phone call that left him stunned.

Richard “Dana” Moore, a private collector from Virginia, had called Stephenson out-of-the-blue with a story that at first brush sounded like an Antiques Roadshow setup.

Months earlier, Moore had been scrolling for artifacts to bid on online when he landed on true treasure: Goodwill, of all places, was selling a fragment of fabric purported to be a piece of George Washington’s war tent.

The war tent is the crown jewel of the museum’s collection, a talisman of the country’s founding that has its own theater wing at the museum where, in a special show, it’s recognized as a symbol of the endurance — and the fragility — of American democracy. Technically, Washington carried around two tents as he battled the British: a dining tent that is stored at the Smithsonian and his more cozy sleeping and office marquee that accompanied it, which is what’s on display in Philadelphia.

But over the years, nine other scraps of those tents had been cut away for use as keepsakes. Nearly all of them are on display at the museum, having been preserved by institutions or by families who treasured the scraps and passed them down through generations.

A $1,300 bid

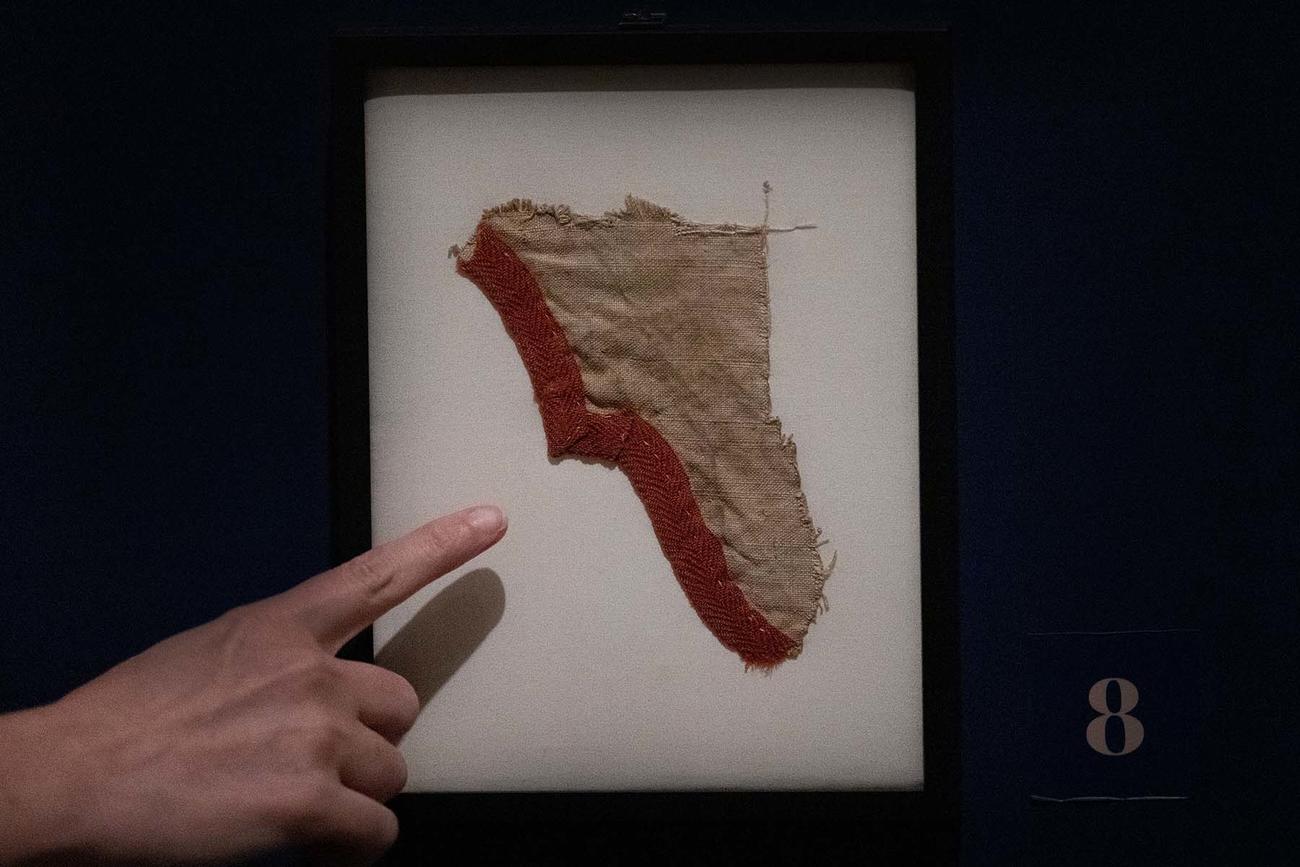

No one expected to find another one at Goodwill, least of all Moore, who secured the fraying piece of fabric with scalloped red trim for a mere $1,300. It came framed, cheaply, with a worn, handwritten note that said the fragment had been taken from George Washington’s tent when it was exhibited in Jamestown, Va. in 1907.

Moore, 70, a physical security specialist for the federal government, believed it could be the real deal — but he couldn’t be sure. It sat safely on a shelf in his den for a year until one night, watching television, he came across a program about the Museum of the American Revolution and its tent display.

“I was overwhelmed. I had tears in my eyes. And I just thought it was the right thing to do,” he said. “People have to see this.”

When he took the call from Moore, Stephenson was in the midst of final planning for a major new exhibition on the history of the tent and its journey to the museum, “Witness to Revolution: The Unlikely Travels of Washington’s Tent.” Finding a fragment of the tent, which had its own unlikely travels, seemed almost too good to be true.

But once it was in conservators’ hands at the museum, it was clear the fragment was real.

“It was an unlikely scenario — an American treasure coming out of the blue,” Stephenson said.

The proof and meaning

Matthew Skic, curator of exhibitions at the Revolution museum, said museum researchers were able to match the fabric’s red worsted wool trim and distinctive trimming to a section of the dining tent’s valance that had been cut away.

The scrawled note also proved critical, he said, even if little is known about John Burns, the man who signed it — whether he was a dignitary at the 1907 exposition in Jamestown or just someone who got close to the tent with a sharp object.

Regardless, Skic said, it speaks to the pull the tents have had on generations of Americans, that someone like Burns would be compelled to want a piece of it for himself. The tents, made for Washington in a Reading, Pa. factory in 1778, unlike many other relics, have never spent long in storage — they have re-emerged, over nearly two centuries, as a unique symbol of the American experiment.

“It’s been kind of deployed by different generations of Americans over time,” said Skic. “We can use the tent as an entry point into different episodes in American history to learn about Americans at those times. It’s a symbol of Washington’s leadership during the Revolutionary War, but also the fragile American experiment in liberty, equality, and self government. It’s been brought out generation after generation to serve as a way of connecting with the founding of the nation.”

A savvy commander, Washington made use of his tents as a symbol to steady his troops. Wherever his army traveled, Washington made a point of setting his tent on the highest hill, Stephenson said.

“So that it would be the first thing 8,000 men saw when they crawled out of their tents in the morning,” he said. “Or at night when they looked over their shoulders and would see the candles still burning in the commander’s tent.”

Over time, the symbol only grew.

During the Civil War Union troops confiscated the tents from the Arlington, Va. mansion owned by Mary Custis Lee, a granddaughter of Martha Washington, and her husband, the commander of the Confederate army, Robert E. Lee. A woman named Selina Gray, who had been born into slavery on the plantation, had tipped the soldiers off. Custis had ordered Gray to lock the tents away.

“She let the army authorities know the relics were in danger,” Skic said.

Later, the tents were a top drawer for the millions who attended the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876.

The tent’s power was not lost on Moore, a Vietnam War veteran who now works as a security specialist for the federal government, and has loaned his scrap of history to the museum for two years.

Earlier this month, Moore and his wife, Susan Bowan, visited the Revolution museum for the new exhibit. Seeing it displayed in the museum was an overwhelming experience, he said.

“People need to see it,” he said. “It’s the real deal.”

_____

©2024 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

© Copyright 2024 Philadelphia Inquirer. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.