Twenty years and one new hip later, Alice Smith is still at it, tackling thickets of records and slogging through swamps in search of an elusive alligator.

She’s not just looking for any gator, though. She’s on the hunt for Alligator Jr., a possibly 30-foot-long, 30-ton waterlogged iron prototype of a Union Civil War submarine believed to be sunk in the area of the Rancocas Creek watershed near Riverside, Burlington County.

For 20 years her search has been strewed with tantalizing clues that ultimately have turned out to be red herrings. An impressive, all-volunteer team she’s assembled have used various devices over the years including magnetometers, sonar, compasses, drones — even duct tape and a boogie board.

Now, she thinks the team has a promising lead.

“I was 56 when I started this,” said Smith, a retired president of the Riverside Historical Society who lives in Delran. “Right now I’m 76. So I decided this is our last-ditch effort, my last-ditch effort. If I don’t find it, I guess I’ll give up the quest.”

Smith’s team includes a researcher from Stockton University, a past president of the Massachusetts-based Navy and Marine Living History Association, and the founder of a Maine-based sonar technology company, among other volunteers. At times, she’s spent her own money, convinced the submarine is out there.

For the first time, she’s raising funds from the public, reinvigorated in the quest after a World War II-era compass started spinning during an April 2023 foray. The compass indicated there was a large metal object buried in the muck. She’s raised $7,119 of $9,100 needed to hire a specially equipped drone. She’s keeping the exact location secret for now.

What’s Alligator Jr.?

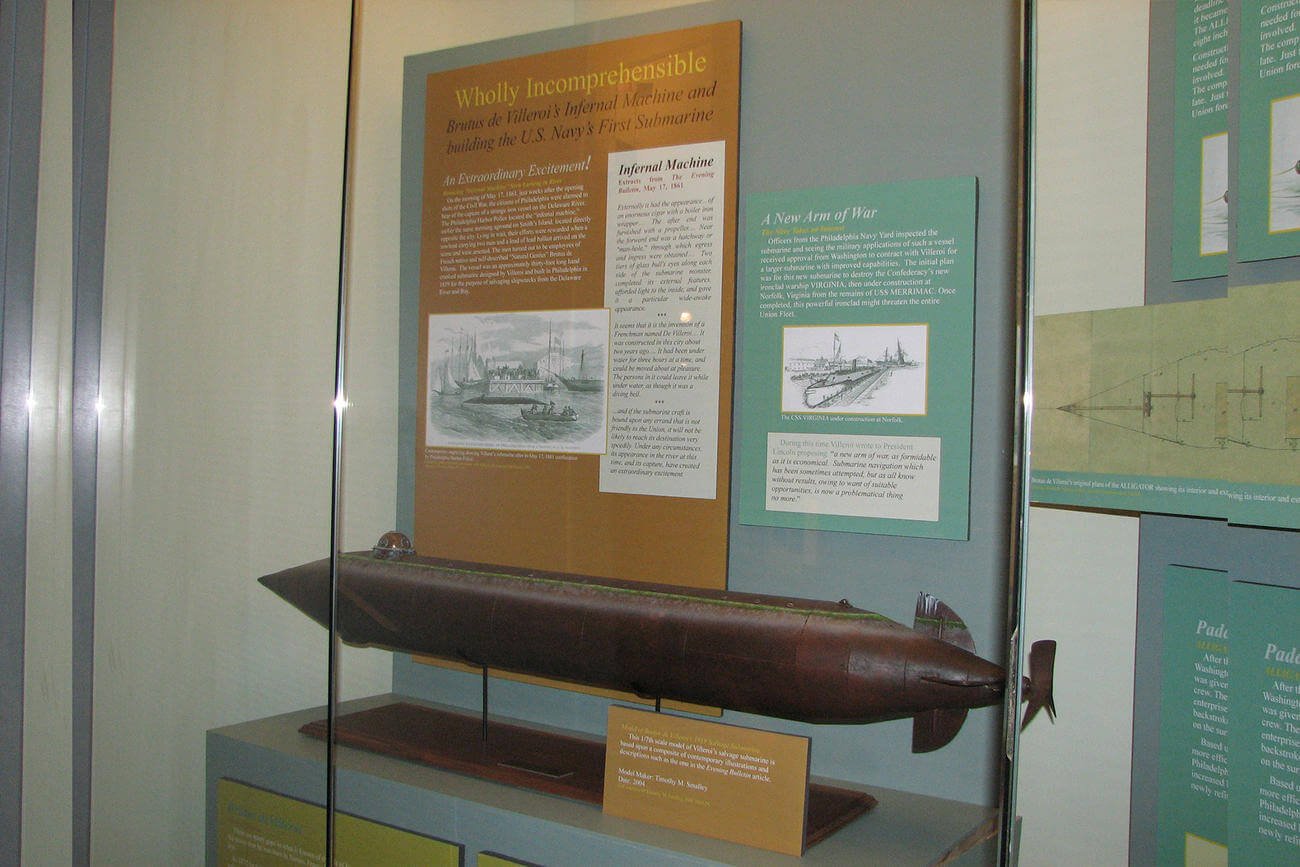

The iron-hulled Alligator Jr., a submarine prototype, was originally built in 1859 for salvage work by French-born inventor Brutus de Villeroi of France. He offered her to the Navy not long after Fort Sumter was fired on, according to the nonprofit Navy and Marine Living History Association. It was bound for testing at the Philadelphia Navy Base when harbor police in the Delaware seized it in 1861.

But the vessel marked the first step toward creation of a modern submarine fleet and had been stored at the Philadelphia Navy Base and Marcus Hook, according to government records and newspapers. It was last traced to Delanco and Riverside where it was believed sunk by its creator.

De Villeroi’s full-scale, much larger 40-foot-long Alligator was built at what is now Penn Treaty Park in Philadelphia as the Navy’s first submarine. President Abraham Lincoln watched a demonstration of Alligator for its war potential. But it sank in 1863 off Hatteras, N.C., and has never been found. And most expect it never will be.

Smith’s research led her to believe De Villeroi had returned to France with the inner workings of its predecessor, dubbed Alligator Jr. by Smith’s searchers. Archives indicate De Villeroi, who immigrated to the U.S. in 1857 and settled in Philadelphia, sunk its shell somewhere along the Rancocas near Riverside and Delanco, just off the Delaware River. She believes the submarine would be a historic find, and answer questions about technology De Villeroi used at the time.

An Inquirer story from 2005 about Smith’s search prompted locals to tell stories of a rusted hull hidden amid phragmite and spatterdock along the creek, including one tale that men were buried inside. Some claimed a large metal object rested under a rope swing on a tree branch.

However, a number of leads have failed to pan out, including a promising magnetic anomaly detected in 2005. But $30,000 worth of equipment including a magnetometer duct taped to a boogie board, showed it to be a false lead.

Clues began popping up more recently. An April 2023 trek into a marshy tributary of the Rancocas with volunteer Allen Rowles bearing a World War II-era compass made at the Watch Case building in Riverside detected a large metal object buried in the mud. A compass can be impacted by the magnetic field given off by iron.

“The compass started spinning,” Smith said.

Then, came another clue at the location.

Drones and Magnetometers

Smith has been working for years with Steve Nagiewicz, an adjunct faculty member of Marine Science at Stockton University. Nagiewicz is a divemaster and specializes in remote sensing technology and marine archaeology.

About eight years ago, Nagiewicz borrowed a boat from Stockton equipped with a magnetometer, which measures magnetic fields, and really didn’t find evidence of a buried submarine. The problem, for researchers, is that high-tension wires, pipelines, buried metal drums, and other objects can throw things off.

Nagiewicz returned this spring with another Stockton faculty member, Mark Sullivan. They flew a drone over the secret location.

“We took some images, put together a video, and examined all of it,” Nagiewicz said. “We found a couple of areas in the marsh with depressions, which indicate that there’s something buried underneath.”

But what’s really needed, Nagiewicz said, is a drone equipped with a magnetometer that can pass over the area multiple times and stitch together a mosaic, giving an idea of the size and shape of what might be underneath, effectively eliminating whether it’s “a bunch of old sewer pipes or some 55-gallon drums someone buried years ago.”

A sizable enough magnetic hit would indicate an object large enough to be the sub.

But, if it is found, excavating 30 tons of iron from the mud would be a big project, Nagiewicz said, and it’s not clear who would pay for that.

‘There’s Something Down There’

Chuck Veit, president emeritus of the Navy and Marine Living History Association, said he believes the search area is promising. He worked with Smith to set up a GoFundMe page to raise money to hire the specially equipped drone. He said, however, that the team is under pressure because the price for the drone is only good until fall.

“This is the very best shot we have and the fact that we turned up those two anomalies just cinches it for me,” Veit said. “There’s something down there.”

Vince Capone, founder of Black Laser Learning, a sonar technology company, has helped Smith for years. He has experience finding shipwrecks and other underwater objects. When he actively volunteered on the search, he lived in Delaware. Now, he lives in Maine and still acts as a technical adviser.

Sonar won’t work in the deep muck, he said. The drone and magnetometer combination will give a good idea whether something large is buried or not. A big enough “signature” would rule out a pipe or boiler. He’s not jumping to conclusions, but said finding Alligator Jr. would be a significant achievement.

Regardless of the outcome, Capone has clear admiration for Smith and her quest.

“Alice has done an amazing amount of research,” Capone said. “It’s not like she’s just dreamed this up. She has gone through all the archives. She has produced credible data that the submarine could be in this location. You put those two things together and you have a very exciting possibility that it could be right here in the Philadelphia area.”

(c) 2024 The Philadelphia Inquirer

Visit The Philadelphia Inquirer at www.inquirer.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

© Copyright 2024 The Philadelphia Inquirer. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.