A Marine Corps investigation released late Friday into an MV-22 Osprey crash off the northern coast of Australia that led to three fatalities last August pointed to “pilot error and complacency” as causing the accident.

The investigation also found “several concerning maintenance practices” by the unit, Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 363. And, while investigators did not directly blame those practices for causing the crash, it concluded that the tiltrotor aircraft never should have been certified safe-for-flight that day.

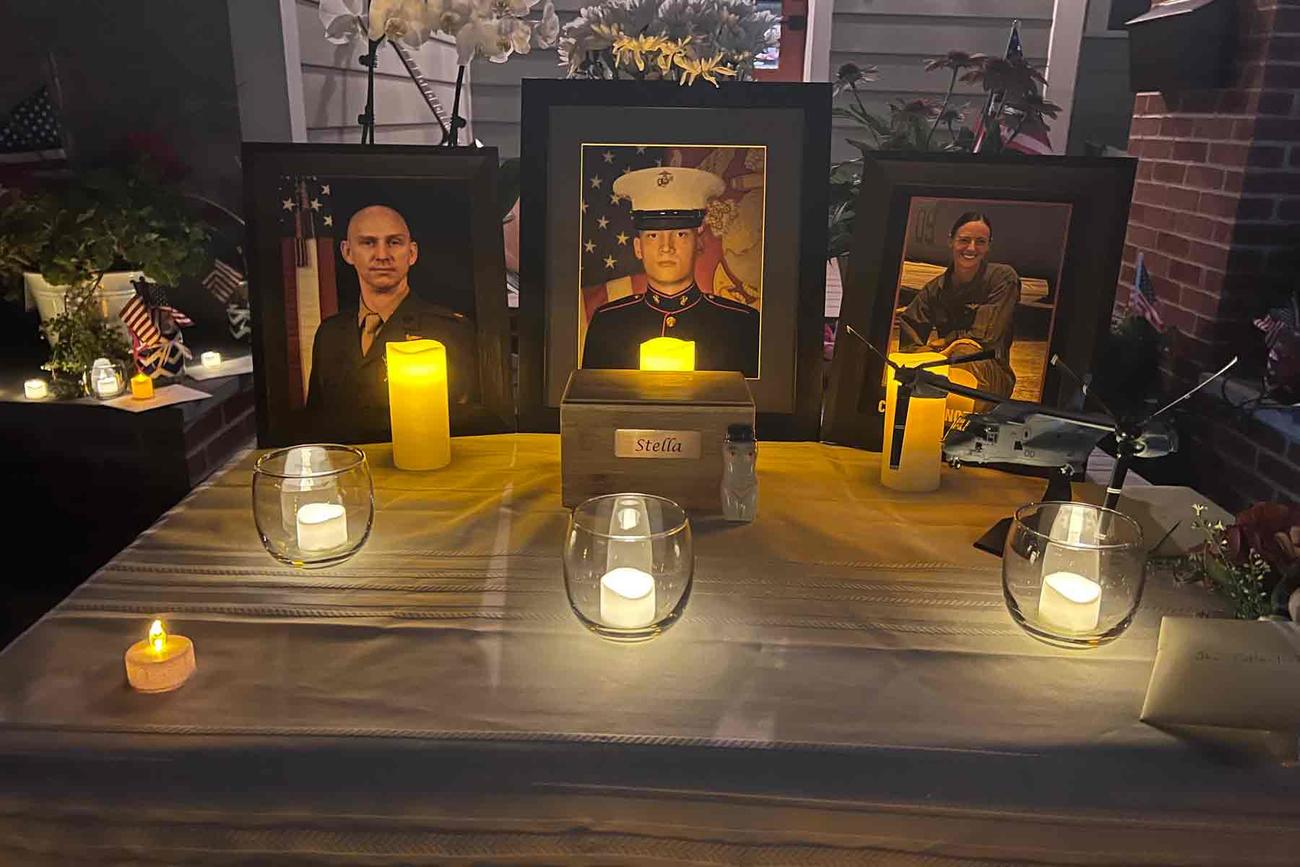

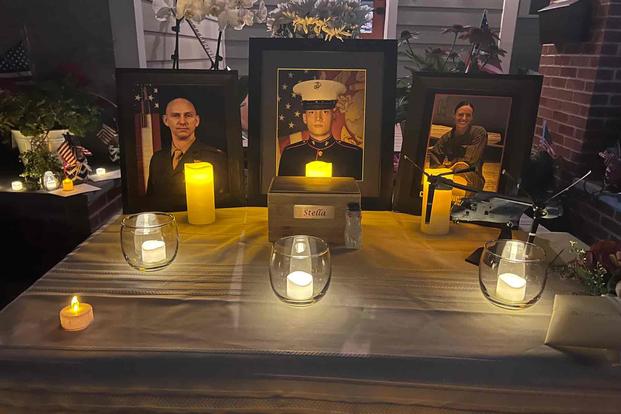

The Osprey was flying as part of Exercise Predator’s Run when it crashed on Melville Island, north of the Australian city of Darwin. Two Marine pilots, Maj. Tobin Lewis and Capt. Eleanor LeBeau, were killed in the crash, and another Marine, crew chief Cpl. Spencer Collart, died in an attempt to rescue them. Twenty other Marines survived the crash.

Read Next: The VA’s 2023 Hiring Spree: A Lot of Psychiatrists

Collart’s family thought that he died in the initial crash, and were not told of the rescue attempt until earlier this month, nearly a year after the crash, they told Military.com in an interview.

Lewis, the executive officer of the unit who was simultaneously serving as the “acting commander for the squadron” and the aircraft lead for the mission, was responsible for overseeing the planning and execution of the operation.

The final report from investigators recommended that at least two members of Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 363 be punished. One Marine facing potential administrative action was the commander of the unit at the time, Lt. Col. Joe Whitefield, for “permitting a culture that disregarded safety of flight and aviation maintenance procedures,” the report said.

When reached by phone Sunday, Whitefield declined to comment on the investigation and referred Military.com to Marine Corps headquarters public affairs. According to public Marine Corps photos, Whitefield relinquished command of the squadron in a ceremony roughly four months after the crash.

The other Marine, who was not directly identified in the investigation and served as the Maintenance Material Control Officer at the time, was accused in the investigation of dereliction of duty and providing a false statement, charges under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

The investigation found that Lewis, one of the pilots, did not sign off on weight and risk documents prior to flight — one that was part of a complex multinational training exercise but appeared to be rushed and riddled with miscommunication, according to investigators. None of the unit’s leaders stopped the aircraft from flying that day, though at one point one of the pilots considered executing the mission with just one of the two Ospreys that were scheduled to partake in the exercise “due to maintenance troubleshooting” with the lead aircraft.

One former MV-22 pilot who served with Lewis at multiple squadrons told Military.com that they were surprised that the crash was not due to mechanical failure and expressed confidence in and admiration for Lewis’ flying abilities.

According to the investigation, while there were problems with the preflight procedures, they were not the direct cause of the crash.

One problem was fuel. Lewis and LeBeau’s Osprey was fully manned and had an excess of 2,000 pounds of fuel when they took off, despite the unit planning calling for less gas and the crew trying to burn off as much of it before the flight as possible.

The former pilot noted that the extra weight would have been unhelpful while the crew was trying to maneuver as the aircraft was going down.

Lewis was in a coaching role during the flight. That meant LeBeau, a more junior pilot, was in control of the aircraft during a majority of the flight, the investigators noted.

The Ospreys were flying in formation with Lewis and LeBeau’s aircraft in the rear. In the last minutes of the flight and as the aircraft were preparing to land, the lead Osprey in the sortie reduced speed because the pilot “was not within normal parameters for the approach to landing as planned,” the investigation said. As a result, the lead Osprey reduced speed, causing the two aircraft to come within 300 feet of each other.

Lewis and LeBeau’s Osprey reacted by banking dramatically — then banking twice more. Crew in the lead aircraft said they could hear the second Osprey’s rotors and engines “over the top of them,” the investigation found.

Stall warnings blared in the trailing aircraft, and it was “nose-down” as it approached the ground. Lewis took over in the final moments, pulling back on the controls with both hands in an attempt to level the Osprey and slow its speed into the trees. The Osprey crashed just 15 minutes after it took off; 20 of the 23 Marines aboard survived.

Collart died after he “heroically reentered the burning cockpit of the aircraft in an attempt to rescue the trapped pilots,” the investigation said. “He perished during this effort.”

Members of Collart’s family told Military.com that they were shocked, but ultimately proud, when they first heard last week that their son bravely reentered the downed aircraft “trying to save his friends,” his father said.

“I can’t say I’m surprised,” Bart Collart told Military.com in a phone interview Saturday. “Of course, our initial reaction was, ‘You silly, silly brave boy, why did you do that?'”

Last week, Marine Corps officials briefed Collart’s family — and throughout the week, other families affected by the crash — handing over three large binders that included details, interviews and pre-flight plans as part of their investigation.

“We’re so proud of Spencer,” Bart Collart said. “He was just a complete badass going in there and trying to save his friends, and I totally get that — I can’t blame him for that. … I just wish that somehow he could have made it back out and still be here with us.”

The Osprey — which can fly fixed-wing and rotor-wing — has a complicated history as an aircraft, both as a critical asset in the Marine Corps’ arsenal as it faces increased challenges in the Pacific and one with a problematic pattern of crashes and maintenance issues.

Since the Osprey began flying in 1992, crashes of the aircraft have led to 60 fatalities. Nearly all of those crashes have been attributed to pilot error, and service officials have often noted that the aircraft is flown frequently, meaning the number of incidents per hour in the air is relatively low.

The Australia crash marks the fourth fatal Osprey accident in just the last two years, and its investigation comes on the heels of another crash report that laid partial blame on the pilots despite catastrophic issues with the aircraft’s gearbox. That crash, which occurred in November 2023, killed eight airmen when the Air Force version of the Osprey went down off the coast of Japan.

Investigators recommended that all Marine Corps Osprey squadrons conduct a stand-down in the wake of the crash. But families still have outstanding questions on what will be done so “this never happens again,” said Alexia Collart, Spencer’s mother.

Alexia said she hopes that the Marine Corps will find ways to make it easier for pilots to survive crashes. The second issue she emphasized was the training and the culture of safety in the squadron.

“They responded the best they could, and we all look at this three-binder report, and they had to react in seconds,” Bart Collart said, adding that despite the crash, the other 20 Marines survived. “I think a lot of that is to be commended for Tobin and Ellie, and they’re not getting any of that from the report, which is disappointing to us.”