Bats use echolocation to find food and places to rest. Add in an incendiary device glued to their chest, and you now have a firestorm that can wreak havoc on any enemy. Or so Pennsylvania dental surgeon Dr. Lytle S. Adams thought during World War II.

The problem is that you don’t know where they will go once released. Add to it that it’s generally a bad idea to mix explosives, adhesives, and wildlife.

On Dec. 7, 1941, Adams made a fateful trip to the Carlsbad Caverns National Park during a vacation to New Mexico. He was awed by the hundreds of thousands of bats that nested in the caves.

The bats were still on his mind later in day as he drove away when news came across the car’s radio of the attack on Pearl Harbor. According to the National Institute of Health, he was “outraged over this travesty, [Adams] began to mentally construct a plan for U.S. retaliation.”

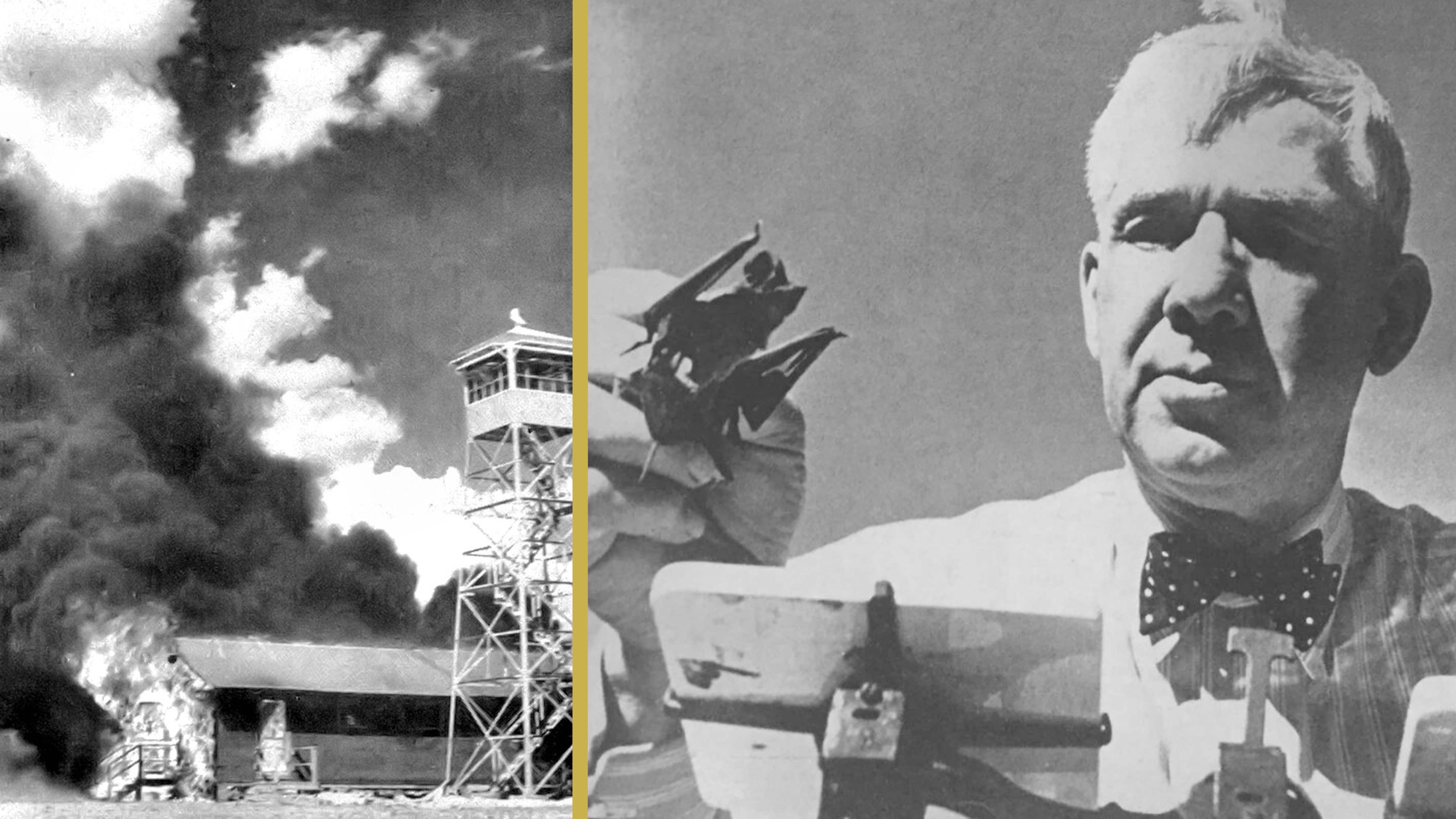

The idea Adams came up with — a ‘bat bomb,’ with 1,000 bats carrying napalm into a city full of wooden buildings — led to one of the U.S.’s most bizarre weapons development programs of all time, one that Adams believed could bring about a quick end of the war but did little more than burn down a flight training base in the U.S.

Adams knew that buildings in Japanese cities were predominantly built of wood. His idea was to develop an empty bomb case that, rather than hold explosives, would hold 1,040 bats toting napalm-like incendiary gel with timed fuses. Dropped over Tokyo, the bats would create a hellish cyclone with incendiary devices throughout Tokyo, hopefully bringing about an end to World War II

Adams put his idea in a letter to the White House, where he had professional contacts who got the letter to President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was interested, if cautious, telling staffers, “This man is not a nut. It sounds like a perfectly wild idea but is worth looking into,” according to author Jack Couffer’s book, “Bat Bomb: World War II’s Other Secret Weapon.”

Couffer was a young filmmaker who had grown up studying bats and other birds as a teenager. He would go on to a career making dozens of nature documentaries, but he was drafted into the Army early in World War II and assigned to the bat bomb project and witnessed much of its three-year development.

The development and testing, dubbed Project X-Ray, was based in New Mexico. The program developed a metal bomb casing with three horizontal layers, similar to upside-down ice cube trays, where bats would nest. To keep them docile — or as docile as a bat strapped with a bomb can be — they would be placed in an artificial cold-induced hibernation. The “bat bomb” was designed to be released from high altitudes just before dawn, when bats naturally seek out a place to sleep during the daylight hours.

According to Couffer, the bombshell’s parachute would deploy at 4,000 feet, slowing the descent. At approximately 1,000 feet, the bats would awaken as the surrounding air warmed, and the bomb casing would release the bats. The team expected the bats to seek out attics and eaves under roofs in the city below.

A timed fuse for the incendiary device would allow the bats to find a place to sleep before detonating somewhere within their 20 to 40-mile flight radius.

In his letter to the White House, Adams called the bat the “lowest form of animal life.” He believed that bats were created “by God to await this hour to play their part in the scheme of free human existence and to frustrate any attempt of those who dare desecrate our way of life.”

This was pre-PETA, of course. According to Couffer, the reality of sacrificing over a million bats during the project’s life was never brought up during discussions, planning, and testing. But while writing the book during the “day of animal rights activism and the conservation ethic,” he explained his thoughts:

“If times have changed, so have I. It’s hard to imagine now putting myself into a frame of mind to kill a million anything — birds, bats, or bumblebees,” Couffer wrote. “It is just not within the realm of my creed at this time. But then it was, and because of the perceived greater good, I was ready for the sacrifice without a second thought.”

Testing began in 1943, with thousands of bats captured in the very cave that inspired Adams’ plan, Carlsbad Caverns. The first “bat bomb” test took place on May 15, 1943, at Carlsbad Army Air Corps Base in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

The bomb was released from an Army Air Corps B-25 bomber and appeared at first to work. The parachute deployed, and the bats flew free of the shell carrying dummy incendiary devices.

But, as Couffer recalled in his book, an unexpectedly strong wind carried the bats further away than expected. With no bats to photograph, Signal Corps photographers asked if the team could stage other bats for photos and films — this time, using live incendiary devices.

As the team prepared more dormant bats for the photos, the Carlsbad heat awoke them. With incendiary devices activated, the bats flew off and took refuge in an air traffic control tower, barracks, and several other buildings — all newly built for the Army Air Corps.

When the bats detonated, they set the new base on fire. Firefighting resources were not activated in order to protect the secrecy of the project. Though there were no reported injuries or deaths, the boondoggle did result in one very upset Army Air Corps commander whose new base was burned to the ground.

Though the test was deemed successful, the Manhattan Project made more progress in less time. In October 1944, Project X-Ray was officially terminated by military brass in Washington, and the bat bomb was never used again.

And that’s probably for the best.