Editor’s note: This story first appeared on March 5, 2019.

Sgt. Mike Parsons should have died that day.

On the morning of July 3, 2018, the Tulsa, Oklahoma police officer was among a group of officers who stopped John Terry Chatman Jr. at a QuikTrip gas pump after noticing a discrepancy between the van Chatman was driving and his license plates.

Chatman was irate. The 34-year-old felon “challenged the officers’ jurisdiction several times and asked the police officers to contact their superiors” until Parsons, a 25-year veteran of the department, arrived to support his fellow officers with a non-lethal pepper-ball gun, according to a timeline of the encounter

compiled by The Tulsa World and video footage from the scene.

“Less than 10 seconds” after Parsons loosed off a pepper ball, Chatman opened fire. As

captured on video by Tulsa police body cameras, Parsons was shot in the leg, and two fellow officers dragged him out of the kill zone.

Somehow, Parsons was fine.

Instead of succumbing to shock, Parsons was alert and at work minutes after being wounded. One of his fellow officers, Con Ericsson, worried that the bullet had fractured a femur or hit his femoral artery, but he observed no signs of shock or swelling.

Parsons took command of the scene, making decisions and coordinating his fellow officers as they moved in to arrest Chatman.

With Chatman in custody, EMTs put Parsons in the back of an ambulance and cut away his pants to get a better look at his injury.

That’s when a coin clattered to the floor of the ambulance. Larger than a quarter, there was clearly a dent in the piece of metal. Ericsson held it up to the injury; sure enough, the dent matched the pattern of bruising on Parsons’ leg.

Ericsson recognized the coin almost immediately: It was the challenge coin that a friend had given him as an incentive to make the leap from enlisted to officer in the Navy — and it was the same coin he’d insisted Parsons carry on his person just weeks before the shooting.

“He was meant to carry that coin,” Ericsson, 43, told Task & Purpose. “He was meant to go home to his family.”

The chance collision of Chatman’s bullet and Ericsson’s Navy challenge coin in Parsons’ pocket on that fateful day in Tulsa was more than two decades in the making.

Born in Idaho, Ericsson joined the Marines in 1996 after a two-year stint on a Mormon mission at a Navajo reservation in Arizona. He was assigned to the 4th Marine Air Wing as an Expeditionary Airfield Systems Technician (0711), trained to set up airfields and forward operating bases for close air support aircraft and the rescue of downed pilots.

In 1998, he received an honorable discharge from the Marines and was transferred to the Army’s 45th Infantry Division, part of the Oklahoma Army National Guard, where he trained as a sniper until 2006. During that time, he joined the Tulsa Police Department.

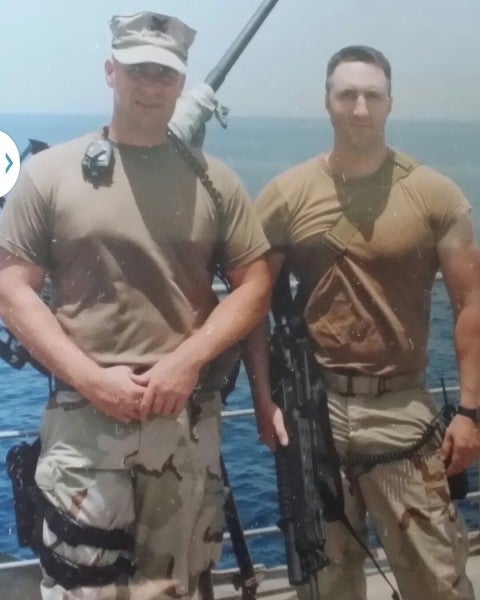

After a two-year sabbatical of sorts from the armed forces, Ericsson joined the Navy Reserve in 2008, putting the sniper skills he developed in the Army to good use first with a costal riverine squadron and then as a member of a Maritime Expeditionary Security Squadron 6, one of the 12-man security teams tasked with protecting U.S. Navy ships.

Later, he deployed to the Gulf of Aden for anti-piracy missions, and from 2010 to 2013, he worked for the Naval Criminal Investigative Service out of Chicago, providing personal security details and teaching anti-terror classes to enlisted officers.

After years of honing his skills with precision weapons, Ericsson started EMT training in 2016, around the same time that he was assigned to the Tulsa PD’s special operations team. A major driver of his decision to become a medic stemmed from the 2003 loss of his sister in a car accident, and the death of his brother less than a year later. Choc Ericsson, an Oklahoma state narcotics officer, was killed in the line of duty when he was reportedly

run over by a driver high on meth.

Part of the reason they were lost, Ericsson said, was because “nobody knew what to do at the scene.”

“It doesn’t ruin a life; it ruins

lives,” said Ericsson, describing how his family coped with the back-to-back losses.

Nearly 20 years after he first took his enlistment oath, the Mustang challenge coin was put in his hands in March 2018, just a few months before the shootout with Chatman at the QuikTrip, by a friend who “recruited me to convert from enlisted to officer” while he attended a Limited Duty Officer conference in California. Six months later, on October 1, Ericsson become an officer.

“It meant a lot to me,” Ericsson told Task & Purpose. “I’d worked for years to get that coin, and when it was presented to me, it was fulfilling a lifelong dream.”

* * *

Ericsson and Parsons had served on the Tulsa PD together for years, but they didn’t become close until Ericsson joined the special operations team as a tactical medic.

“Our squads are right next to each other geographically, and I knew Mike [Parsons] by reputation,” Ericsson said. “He was one of the first people I went to about trying out for special operations. He looked at my certifications and said, ‘you need to try this.’”

There were two incidents that made the two especially close. On April 2, 2018, Ericcson and Parsons responded to a call at The Coffee Bunker, a well-known Tulsa haunt for post-9/11 veterans, where an unstable Army vet had locked himself into an office with a pit bull and was threatening to kill himself with a large knife.

“He had obviously fallen through the cracks at the VA,” Ericsson said. “I thought hey, I’m also military, let me see if i can help you.”

The suspect plunged the knife into his neck, slitting his own throat. The two officers kicked the door in, and while Ericsson blew through his medical gear attempting to treat the man, Parsons took command of the scene, grabbing sheets and shirts to stop the bleeding. Amazingly, the man survived, and both officers visited him in the hospital a few weeks later.

“Mike did such an exceptional job treating this guy,” Ericsson said. “I thought very highly of him after that.”

“Con saved the man’s life,” Parsons said. “It really impressed me. He was very calm, very sure … he was in his element.”

“When someone is fighting the police, you have a dynamic situation,” he added. “We formed a bond because of events like these.”

The second incident came a few months later. In June, Ericsson responded to a call for a suspect on some kind of designer drug.

“He fought me for a good 8 minutes and 47 seconds,” he said. “The guy was doing one-armed pushups with me on top of him … I couldn’t break his grip.”

The suspect was having some mental health issues and his drug use, along with fighting Ericsson, caused him to go into cardiac arrest and experience what law enforcement officials call an “excited delirium event.” Ericsson administered CPR and put out a call for backup.

The first person to show was Parsons.

“He traveled all the way from south Tulsa to north Tulsa to get to us in time,” Ericsson said.

The suspect died in the fight.

“Mike came to me and talked to me, he said, ‘you survived this one, you’ll survive this one and the day after and you’ll keep surviving’” Ericsson said. “He called me every day after that making sure I was OK.”

Shortly after the that incident and just weeks before the July shooting at the QuikTrip, Ericsson handed Parsons a token of his “extreme appreciation” — his challenge coin.

“When I needed somebody the most, he seemed to be there,” Ericsson said. “Any bad situation, any bad calls, he’d come up right to me and we’d work through them together. He was always right there.”

* * *

Con Ericsson’s challenge coin didn’t stop the round that John Terry Chatman Jr. fired at Sgt. Mike Parsons; it simply deflected it. The bullet traveled through the muscle of his leg, avoiding all the major bones and arteries.

According to Parsons, it was his wife, fellow Tulsa PD Sgt. Danielle Bishop, who dragged him away from Chatman’s van. Ericsson arrived on the scene moments later and started administrating medical treatment.

A minute later, the video shows him standing behind a red car, weapon drawn. “Something hit me bad in the thigh,” Parsons says.

“We have to get you out of here, sergeant,” the officer says in the body camera footage.

“Nope,” Parsons

replies. “I don’t care if it’s a fucking cut, or … it fucking hurts, fucking bad.”

In subsequent statements, Tulsa police commended Parsons for continuing to command the scene even after he was shot. Body camera footage showed as much; as his fellow officers took cover and new ones arrived, Parsons continued to bark orders and organize the arrest team to take Chatman into custody.

He wasn’t even sure he was shot; in the body camera footage, an officer asks if he’d been hit less than a minute after the shooting. “I think so,” he responded.

“His behavior that day was the best example I’ve ever seen of someone bringing order out of chaos despite external and internal stressors,” Ericsson said. “[Parsons] was able to gain control of the situation despite his injury and was able to command the arrest and cover team and make commands to the suspect.”

In retrospect, both Ericsson and Parsons know the shooting could have gone sideways very fast. In an interview with Task & Purpose, Parsons recalled that, shortly after Ericsson had given him the challenge coin, he’d chided Parsons for not having it on him.

“He’d checked on me and asked if i had the coin with me,” Parsons said. “He didn’t admonish me. It was like ‘I just really need you to carry that coin.”

“I remember thinking, ‘you were meant to survive this,’” Ericsson said, recalling Parsons’ words to him after the June incident that left him rattled. “‘Everything that happened this year was meant to happen. You were meant to have the coin, you were meant to go home to your family.’”

Chatman currently faces life in prison after being convicted on charges related to the July shooting. Parsons will start his 27th year on the Tulsa police force this coming May alongside his wife, Officer Bishop. They have three beautiful daughters; both Parsons and Ericsson believe that “God had a hand” in that coin ending up in the former’s pocket.

But for Parsons, the coin is just a symbol of the more important force that helped save his life that day: the bonds of brotherhood he’d forged with Ericsson and others in the Tulsa PD.

“A lot of people talk about this coin, and i get it; it’s very interesting how that all transpired and what happened,” he said. “But for me, that’s just one part of it … the other part of it is how well everyone worked together. It was a violent, dynamic day, and it was violent, but it just goes to show what men and women in uniform do every day in this country.”