Bobby Hogue woke up on his office floor covered in jet fuel. Thick black smoke consumed the room, dancing in a searing amber glow. Hogue’s head and ears pounded. His body throbbed with pain. As he pulled himself to his feet, the reality unfolding around him began to sink in. Through a crack in the floor, he could see a raging inferno on the deck below. He yelled out to his three office mates. All of them were injured, one so concussed he could barely move. Hogue stumbled to the only door in the office and pulled the handle with all of his strength. The explosion had wedged the door shut. They were trapped.

For five minutes, one of the trapped men, Cpl. Tim Garofola, strained to pry open the door, creating a crevice. As fire began to melt objects to the floor, the building ached and moaned around them. After the group squeezed through the doorway, they stepped into another apocalyptic scene. They had two options: Escape through the south corridor, which had collapsed during the blast; or use the north corridor, engulfed in flames and billowing smoke.

As they contemplated which direction to run, they heard a voice from behind the black veil.

“If you can hear my voice,” came a call, “come this way.”

Just as they looked down the hallway, the heat and structural damage caused several of the office doors to explode, driving wooden shards deep into the walls. They had no time to think about options. As Hogue helped his injured coworker to safety through the smoke toward the voice down the hallway, Garofola searched nearby rooms for survivors, saving at least two people. “Fire wasn’t the scariest part,” Hogue told The War Horse during months of interviews. “It was the threat of collapse.”

The group rushed down the halls and stairways as a growing trail of people followed. All searched for a path to safety. The security at the Pentagon, meant to keep enemies from breaching its perimeter, had trapped them within the fortified walls.

They pushed past security guards, who tried to keep them inside as if it were a normal day, so they could use a restricted subway entrance and exit the Pentagon into a parking lot. Hogue dug into his pants pocket, relieved to find his car keys. As the group rushed to his sedan, a major he escaped with pulled out a cell phone. Lines were jammed and the major was unable to reach his family, so Hogue tried to call his wife. When she answered, he could barely hear her, as his ears still rang from the blast. The major spoke for Hogue and then relayed phone numbers from nearby strangers in the crowd, who begged Hogue’s wife to tell their families they were alive.

As Hogue looked around, he began to “succumb to the concussion,” the fear, and “the weight of responsibility,” he said. Helping the mass of people in distress felt insurmountable. Hogue urged his group to cram into his car so they could drive to the nearby home of his office mate Peter Murphy, the senior counsel for the commandant, who had been injured during the blast. As Hogue looked back in his rearview mirror, he saw smoke fill the air and emergency lights flash in the distance.

[embedded content]

After the group pulled into Murphy’s driveway, they rushed inside, where Hogue explained to Murphy’s wife what had happened. They watched on television as the north tower of the World Trade Center collapsed. It was 10:28 a.m.

While the dust in lower Manhattan began to settle, Hogue got back in his car and drove to his Springfield home with Maj. Joe Baker, whose cell phone he had borrowed earlier. When he swung open his front door and walked into the foyer, his wife and daughter hugged him, both in tears. As he looked over his wife’s shoulder and peered down the hallway, Hogue saw his then-12-year-old son standing motionless with a blank look in his eyes. It was almost as if he was unable to process seeing his father caked in a toxic coating of ash, Hogue said.

“That’s when reality sank in.”

Leading up to the attack on the Pentagon, Hogue never imagined he would spend his entire professional career as a civil servant in the defense department. He had worked on top-secret weapons programs; litigated military civil rights cases; and seen American conflicts during Desert Storm, Grenada, and Panama, but he never envisioned he would be hand-selected to serve alongside six Marine commandants, the most senior officers in the Corps. As he stood in the shower of his home that afternoon 20 years ago, Hogue reflected on the significance of the attack and how the day also marked the one-year anniversary of him becoming a Senior Executive Service employee, a coveted career achievement among civil servants, as well as his first official day as the deputy counsel for the commandant.

Two decades ago, Hogue couldn’t know how his career choice would affect his life, that even as volunteers pulled bodies—and an important flag—from the wreckage, he would help plan the longest war in U.S. history; that he would guide the Corps through its most radical changes since its founding; and that he would learn the ethos of the Marine Corps. But that day, for the first time, he questioned whether he still wanted the job.

“I never expected the battle to come home,” he said.

As the water ran over his head, and the remnants of his office swirled down the drain, his choice was clear: Semper Fidelis. When Hogue went to bed, he restlessly played the day over and over in his head. He begged his mind to let him fall asleep, but the vertigo and nausea were too strong. Just before midnight, roughly 15 hours after a 757 jumbo jet exploded beneath his office, Hogue’s telephone rang again, and his wife relayed a message.

“The commandant wants to see you first thing in the morning,” she yelled, her hands cupped around her mouth to amplify her voice as his ears were still ringing. “Gunny says, ‘Welcome to the Marine Corps.’”

“You Do What You Gotta Do”

When Hogue pulled into the Pentagon parking lot the morning after the attack, flames still rose from the building, casting an amber glow onto Crystal City. Instead of meeting in their secure section of the Pentagon, some of the Corps’ most senior leaders stood within eyeshot of the rubble and decided to commandeer a workspace. The group trekked across the 42-acre campus to the Annex, a World War II-era building that was the home of Marine Corps headquarters until 1996. Hogue roamed the halls until he saw an open conference room, then gathered boxes of Xerox paper to use as chairs.

“It had crappy windows, crappy plumbing,” Hogue said. “Was very Marine Corps.”

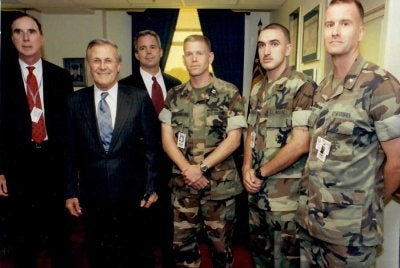

At seven a.m., fewer than 24 hours after the attack, admirals and generals from across the Navy and Marine Corps packed into the room shoulder to shoulder.

“Where I work in the Pentagon, it’s a nice, mostly white-collar kind of existence with a strong military flavor,” Hogue said. “You kind of get accustomed to that. And then something like this happens and all that veneer kind of gets burned away, and you get a strong, healthy reminder: ‘Oh yeah, that’s right. This is the military. We’re going to go fuck something up now.’”

At the start of the meeting, “tempers were high,” Hogue said. The chief of naval operations, Adm. Vern Clark, addressed the room first, Hogue recalled. The Naval operations center in the Pentagon had suffered a direct hit during the attack and 42 sailors were killed. “I want to know who did this,” Hogue recalled Clark saying, “and what we’re going to do about it.”

Over the next few hours, the conversations ranged from top-secret intelligence and troop numbers to logistics and allied forces. One thing was clear: America was preparing for war.

“Beginners talk about tactics,” Hogue said. ”Professionals talk about logistics. On Sept. 12, it really was about: Who do we have? What do they have in their system? Could they be mobilized, and honestly, with no clear idea of where they would be mobilized to.”

Many of the details from the meeting are a foggy memory. “The true fact of the matter is I was struggling physically because I had a terrible concussion. … Today we would call it a traumatic brain injury,” Hogue said, adding that he was increasingly unable to concentrate. “I was having difficulty sitting up. I couldn’t stand for more than a minute or two at a time. I was just in very tough physical shape and, you know, adrenaline will carry you a long way, but even the adrenaline starts to crap out after a while.”

During the meeting, Hogue watched as his injured boss, Murphy, stood up and limped toward a television displaying an image of the Pentagon. Its walls were torn open and full of smouldering debris. Murphy lifted his finger, Hogue said, and pointed to a Marine Corps flag hanging on an interior wall, no longer hidden by blast-proof windows. “That’s my office,” Murphy said, then he sat back in his chair.

“It was just chilling,” Hogue said. “I started thinking to myself, Holy shit, am I going to sit up for the rest of this meeting or spill out onto the floor. … But you do what you gotta do.”

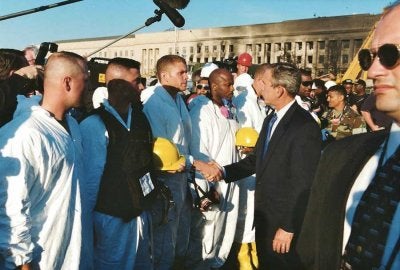

Over the coming days, as Hogue worked alongside the Corps’ leaders to prepare Marines for battle, rescue workers continued to search the Pentagon for survivors. One of them was Eric Jones, a civilian emergency medical technician and graduate student at George Washington University who witnessed the explosion on his way to class. Jones worked alongside burial teams from Arlington and rescue workers to pull corpses from the building, many so charred they crumbled with the slightest touch.

By Sept. 14, his third day at the Pentagon, Jones said he was “emotionally spent” and losing hope that they would find more survivors. He walked out of the first floor with an active-duty soldier on his rescue team and sat on the bumper of a nearby fire truck. As they scanned the rubble, Jones noticed a Marine Corps flag flapping in the wind.

“We looked at each other and said, ‘We need to get that damn flag,’” Jones said during a phone interview. “I’m not a Marine, he’s not a Marine. He was Army. Both of us recognized the significance. … It was a military flag and it was getting ready to fall into the smoldering rubble.”

Jones and his crew used a bucket truck to rescue the flag, and then they delivered it to Marine officials. Two days later, Jones drove to New York City, where he aided efforts at Ground Zero. Jones was later awarded the Secretary of Defense Medal for Valor, the highest civilian award issued for heroism.

As Jones continued his work in New York, and as the sun began to set behind Pentagon city that evening, Gen. Michael J. Williams, the assistant commandant of the Marine Corps, stood at the front of an impromptu formation. “Don’t lose this again,” he told Murphy and Hogue as he presented them with the Marine Corps flag from their office that Jones had saved from the flames. The order, given with a smile, would come to represent much more than a battered red banner adorned with an eagle, a globe, and an anchor.

Following the ceremony, Hogue hung the flag in his makeshift office at the Annex. Soon after, Marines from across the Pentagon stopped by to see and smell the cloth, almost in disbelief the story was true. Having come of age during the Vietnam War, Hogue was struck by their collective reverence toward the standard and thought of how, when he was their age, he doubted the military and questioned whether the government could generate faith in the public.

“Reverence for the symbols of the government or military organizations, it was a unique kind of thing for me,” Hogue said. “I had been exposed already to parades and balls and dinners. I was already onboard and still, I was surprised by this.”

One week after the attack, Hogue decided to get medical help for his injuries. “I just couldn’t deal with it,” he said. “I couldn’t stand, I couldn’t sit for long. I couldn’t hear. I couldn’t focus. My head was killing me.” Hogue was quickly escorted to the Pentagon emergency room. “I thought I was making space for others to get to the head of the line,” Hogue said, but when he arrived, the clinic was empty. During his evaluation, Hogue’s hearing loss was described as “profound,” medical records show, and an otolaryngologist removed chunks of gypsum, cotton, and items Hogue said looked “like chopped up matchsticks with pieces of cement” attached to them from his ears.

“It was just a weird moment,” Hogue said. “The compression is so strong it’s ripping apart the walls and stuffing them into orifices in your body.”

In the coming weeks, as Hogue’s symptoms began to subside and he began his medical recovery, the journey of that Marine Corps flag continued. NASA planned a commemorative launch to the International Space Station that was led by now-Sen. Mark Kelly, a Navy veteran. During the Endeavor’s flight, the Corps’ flag was joined by an American flag rescued from the World Trade Center, a flag that had flown above the Pennsylvania state capitol, and more than 6,000 smaller flags that were distributed to the families of the victims of the attacks.

That same fall, Hogue was in his office when he was forwarded an unexpected call. On the other end was an elderly veteran, who introduced himself only as Robert and said he’d wear a lance corporal’s uniform if he had to, Hogue said. “Nothing about who he was or what he had done. It’s what he was prepared to do.”

He thanked the Marine and hung up, stunned by his continued calling to serve. But as Hogue shared the story with his coworkers and researched the phone number, they identified the Marine as Gen. Robert H. Barrow, the 27th commandant of the Marine Corps, who had retired nearly two decades earlier.

“Where do you find Marines like that?” Hogue said. “I don’t know if you do. I think you make Marines like that.”

But Gen. Barrow wasn’t the only Marine veteran to volunteer to be recalled. “We were getting letters from World War II and Korea Marines,” Hogue said. “It’s that kind of stuff that makes you chuckle until you get your 10th or 15th or 50th letter like that. Then you start realizing like, wow, this is a different kind of outfit. … A different breed.”

“Make Sure That Everyone Makes It Home Alive”

Within 11 months of the attack, reconstruction at the Pentagon reached a point where Hogue could move back into his old office. As on many days before, Hogue parked his car in the executive lot and walked through security toward his office in the outermost “E ring” of the Pentagon. Cameras and senior service members lined the halls to mark the occasion. As Hogue stood where he had almost been killed months earlier, he noticed that the room had been fully restored. The same paint. The same carpet. The same furniture. But on the wall, the Marines hung a small piece of paper. On it was an interdictory circle surrounding a 757 jumbo jet. Below were two words: No airplanes.

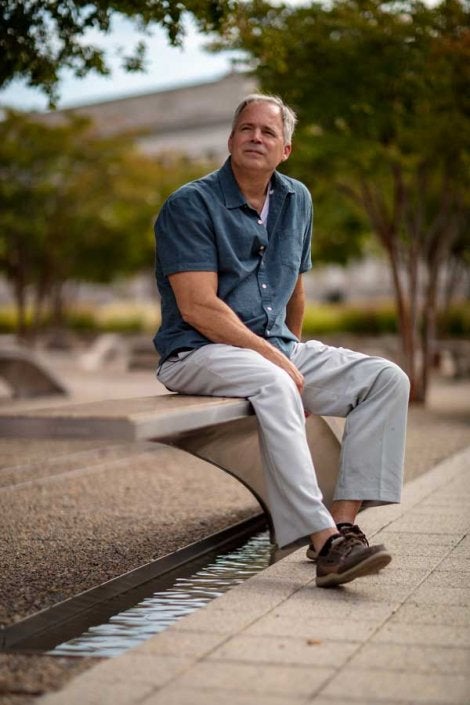

“You have to have a sense of humor to be successful in this space,” Hogue said as he stood in the same office nearly 20 years later. “I knew I’d made the right decision to stick around.”

By 2004, Hogue had been called into a meeting with then-Commandant Gen. Michael Hagee, who served as an infantryman during Vietnam. Hogue’s boss, Peter Murphy, was retiring, and the Corps was searching for his successor. During the interview, Hogue told Gen. Hagee that he didn’t want the job—that he worried about maintaining a work-life balance.

“Within 45 minutes, Marines were in my office boxing up my stuff,” Hogue said. “Nothing I said made any difference at that point. The decision was made, and the only person who had to come to that realization was me.”

Hagee selected Hogue for the job, and, over the next year, Hogue embraced the increased responsibilities. “I didn’t calculate for a second that that kind of honesty was something that he would need or want,” Hogue said.

As Hogue celebrated his first year as counsel for the commandant, the occasion also marked the first anniversary of the war in Iraq. During that time, Hogue frequently heard stories of valor and sacrifice, but during the spring of 2004, a Marine’s selfless act left a lasting impression. On April 14, Cpl. Jason Dunham was wounded in Karabilah, Iraq, after he jumped on an enemy grenade to save the lives of fellow Marines. The grenade ripped through the kevlar helmet and body armor the 22-year-old New York native used to smother the explosion. Dunham’s wounds and brain damage were catastrophic. He was medically evacuated from the battlefield and transported to the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, where he underwent numerous surgeries.

Deb and Dan Dunham met their son—laced with bandages, tubes protruding from his body—inside the hospital. Machinery whirred and chimed in the background. The day after Dunham’s arrival, then-Commandant Gen. Hagee left D.C. to visit the critically wounded corporal and his family. The drive took 30 minutes. Once inside the room of the intensive care unit, a second Marine began reading Dunham the award citation for his Purple Heart as Hagee pinned the military’s oldest medal to Dunham’s chest. Days later, on April 22, Cpl. Jason Dunham died.

Following his death, Dunham was nominated for the Medal of Honor.

“The first time I heard about Dunham, I remember thinking that it could go all the way,” Hogue said of Dunham’s nomination.

If approved, Dunham would be the first recipient of the award since the Vietnam War. For the next two years, as Dunham’s nomination progressed, the wars raged on and Marines found themselves in the longest sustained period of combat since the Vietnam War. Marines fought in cities across Iraq from Baghdad to Nasiriyah. In April 2004, the Corps initiated the First Battle of Fallujah. The following month, Marines pushed through Ramadi.

By the fall, Marines fought the battles of Husaybah and Mosul, and initiated the biggest battle of the war by besieging the city of Fallujah. For more than six weeks, four battalions of Marines fought house to house. In total, 95 service members were killed. Nearly 600 others were awarded the Purple Heart for their wounds. Thousands of enemy fighters were killed or captured, and the advocacy group Iraq Body Count says at least 600 civilians died. Following the battle, 81 awards for valor were presented to Marines, according to Marine officials, including to 25-year-old Sgt. Rafael Peralta, who smothered a grenade blast with his body to protect his fellow Marines. Following a yearslong battle to award the Medal of Honor to the sergeant, when investigators determined he couldn’t have pulled the grenade under his body, Peralta became the only post-9/11 Marine nominee to be denied the Medal of Honor. Sgt. Peralta, who earned his U.S. citizenship while on active duty, was instead recognized with the Navy Cross, the second-highest award for valor.

Throughout the next few years, Hogue said he was driven by the mental images of Marines in combat like Peralta and Dunham who needed his help. In 2006, he helped the Corps deploy thousands of additional Marines to Iraq. The increase was dubbed “the surge,” and as a result of improved technology and medicine, more critically wounded service members returned home with injuries that would define the global war on terror: amputations and brain injuries.

On Jan. 11, 2007, Hogue traveled to the White House with Gen. Hagee where Cpl. Dunham was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by then-President George W. Bush.

“He was a Marine’s Marine who led by example,” the president said during the ceremony, as Dunham’s family members and squadmates sat in the audience. “He was the kind of person who would stop patrols to play street soccer with the Iraqi schoolchildren. He was the guy who signed on for an extra two months in Iraq so he could stay with his squad. As he explained it, he wanted to ‘make sure that everyone makes it home alive.’ Corporal Dunham took that promise seriously and would give his own life to make it good.”

At the ceremony, Hogue spent time speaking with Dunham’s parents, he said. They talked about Dunham’s childhood on their family’s dairy farm and shared stories of a goofy teenager, whom they called Jay. About their son’s phone calls home from Iraq and how much he loved the Marines he served alongside. About how he wanted to make a difference in the world. “She was envisioning her son who, not that long ago, was in high school,” Hogue said. “You’re talking to somebody’s mother and she’s outlived her son. And that’s just a really tough, tough thing.”

There was one thing Hogue says that Dunham’s mother told him that resonates with him to this day.

“The price of freedom is blood.”

“The Opening Salvo of a Generational War”

During the winter of 2007, Hogue began working alongside the incoming commandant, Gen. James Conway, who led Marines during some of the largest battles of the war in Iraq. The onboarding process leading up to Conway’s Senate confirmation took weeks. During that time, Hogue mentored Conway on the intricacies of serving as commandant and navigating life as a public figure, which ranged from discussions about personal investments to weapons acquisition. Conway told The War Horse he was most impressed by Hogue’s humility and desire to serve—that Hogue wanted to empower him as commandant and “draw the line” when necessary.

“His heart was always in the right place,” Conway said about his time with Hogue. “In a 16-mule team, he was easily pulling his fair share and more. … We were absolutely blessed to have him in the office because there was just no equivocation.”

Conway said his experiences in Iraq guided his decisions to focus on improving the gear and equipment, fielding improved body armor and thousands of blast-resistant vehicles. “I actually know it saved lives,” Conway said, adding that, without Hogue’s determination, the project would have taken much longer. “He was enlisting support from, from his counterparts in the building anywhere and every place he could,” and as a result, Conway said the secretary of defense declared body armor “a No. 1 DOD priority.”

In 2008, on the seventh anniversary of 9/11, Hogue attended the unveiling of the National 9/11 Pentagon Memorial. For months, Hogue watched from his fourth-story window as construction crews transformed the blank dirt canvas into a two-acre memorial dotted with dozens of crape myrtles and 184 memorial benches, representing each victim of the attack. A Navy chaplain led the ceremony attendees in prayer. Family members spoke about loved ones killed during the attack. Military leaders recalled stories of heroism among survivors and rescue workers. As they spoke, Hogue thought about how he narrowly escaped death and how much the Corps and world had changed over the previous seven years—about how a peacetime Marine Corps felt like such a distant memory, he said. For years, daily briefings focusing on the number of service members killed made death and sorrow feel normal—an unfortunate, unavoidable byproduct of war.

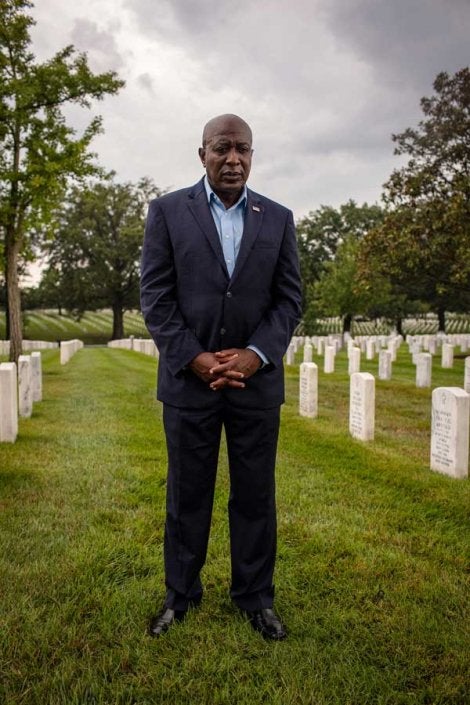

When Hogue walked away from the memorial that fall morning, he reminded himself that the wars weren’t over. That the death and destruction hadn’t ended years earlier. By 2010, Hogue worked alongside Gen. Conway and the Corps’ senior enlisted Marine, Sgt. Maj. Carlton Kent, to deploy a similar “surge” of Marines to Afghanistan to combat a rise in attacks by the Taliban. Like troop numbers, the number of casualties and deaths also rose. As the senior enlisted Marine, Kent carried the image of Marines in combat with him each day he served in his role, he told The War Horse. One experience always came to mind from during his deployment to Iraq: A suicide bomber had killed a vehicle full of Marines, and Kent witnessed survivors collect pieces of the men who had died.

“It affected me by watching them trying to put body parts in a bag that they don’t know what body part goes with what hard-charging Marine,” Kent said, adding that it’s the enlisted Marines who bear the weight of combat. “A great leader is always going to think about how they want to bring back every Marine, but they know that it’s impossible to do that in combat. But deep in their heart, they want to do that.” Nearly a decade after leaving uniform, Kent said not a day goes by that he doesn’t think about the Marines deployed in harm’s way.

During his time leading the Corps’ enlisted ranks, Marine leadership began the process to award the Medal of Honor to its first living recipient since the Vietnam War, a sniper named Sgt. Dakota Meyer. In Ganjgal, Afghanistan, Meyer braved a six-hour ambush against more than 50 Taliban fighters, rescuing multiple service members and Afghan allies.

“Dakota Meyer, he didn’t have to go in and out of that situation like he did all those times,” Kent said, as he recalled the first time he read the award citation. “But that’s not the Marine mentality. … Meyer was an example of what warriors think, especially in the Marine Corps. … They’re never going to leave them in combat, just to hang out there by themselves. They’re willing to sacrifice their lives.”

Leading up to the Marine Corps birthday that year, Nov. 10, Hogue prepared to celebrate alongside Marines young and old, just as he had during many years before. But the day before the event, he received news that put a stop to his cheery mood. First Lt. Robert Kelly, the son of revered Marine leader Lt. Gen. John Kelly, had been killed in an explosion while leading his Marines on a patrol in Afghanistan. Immediately, the Corps’ most senior leadership contacted John Kelly’s best friend, a Marine he’d served alongside for two decades, Hogue said.

“It had to be Joe Dunford who gave him the news.”

Before sunrise on the eve of the Marine Corps birthday, Lt. Gen. Joseph Dunford buttoned his dress uniform like he had done many times before. He polished the brass and shined his Corfram shoes. Then he drove with his wife Ellen to the home of 1st Lt. Kelly’s parents, a short commute through the winding roads of the capital.

“I don’t think we talked much, to be honest with you,” Dunford told The War Horse. ”Just the profound sense of loss for us even knowing him and then knowing how painful this was going to be for the Kellys.”

When the car pulled into the driveway, Dunford opened the car door. As he stepped onto the driveway, he looked toward the front door. He was moments away from telling his longtime friend, a man he had served alongside for decades, that his youngest son was dead. Dunford said he walked from his car to the front porch of Kelly’s home and waited patiently for the lights to turn on. He listened as the general walked downstairs and gathered his things to leave for work.

“It would always be that way when you make the casualty call. It would always be this sense of profound loss and just an extraordinarily difficult thing to bring that kind of news to parents,” Dunford said. “But the long-term personal relationship with the family and with Robert made it that much more difficult.”

When Gen. Kelly walked out of his house before six a.m., he assumed Dunford’s dress uniform was for a birthday ball celebration. “It quickly set in,” Gen. Kelly told The War Horse. Dunford didn’t need to say anything. “His face said it all.”

The three then went inside. Dunford and his wife waited downstairs while Kelly went to tell his wife, Karen, who had just woken up and was getting dressed. In the weeks leading up to the death of their son, Gen. Kelly had visited Marines in the hospital who were wounded in his son’s unit, he said. But the walk up the stairs of his home was far more daunting.

The Dunfords spent the majority of the day with the Kellys. They drove them to see family members to share that Robert had been killed. The first visit was to Robert’s sister Kate, who was working at the Washington headquarters for the American Red Cross. At first, she saw Gen. Dunford and felt excited. “Uncle Joe,” Kelly recalled his daughter saying. “There was this big smile … and then she realized and just collapsed.”

Like other Gold Star families, the Kellys were embraced by the Marines and service members in their lives. In a letter to friends and family, the general reflected on that loss. “We are a broken hearted-but-proud family,” he wrote. “He was a wonderful and precious boy living a meaningful life. He was in exactly the place he wanted to be, doing exactly what he wanted to do, surrounded by the best men on this Earth—his Marines and Navy Doc.”

On Nov. 22, two weeks after their son’s death, John and Karen Kelly drove to Arlington National Cemetery, like they had many times before. There, the Kelly family stood alongside not only friends and family, but the service members and government leaders they’d served alongside. At the close of the ceremony, a volley of gunfire echoed through the trees. A shot to the heart. Twenty-one times over.

“Robert just happens to be one of the people that paid that price,” Kelly said. “When I hear taps or a 21-gun salute, I think about all the Marines who came before me.”

“This Is Morally the Right Thing to Do.”

By 2011, as the global war on terror entered its second decade and the Iraq War came to an end, Hogue began to work alongside his third commandant.

“No other service does this—takes an attorney from out in town and puts them in the smallest council that the commandant uses,” Hogue said. “To know that the tribe, the tribalists of the tribe, have someone like me … built in to be that outside voice … still impresses me.”

During the last 20 years, Hogue was involved in some of the most transformational changes to the Corps since its founding, efforts largely informed by his Catholic upbringing during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, he said. Both of his parents, Ruth and Bill, were strong supporters for civil rights and desegregation, and volunteered Hogue to be bussed to Dr. Charles R. Drew Elementary School in Arlington, Virginia. As one of seven bussed children, and the only one volunteered by his parents, he resented it at the time.

“I was a kid and they took me away from my friends,” Hogue said, but he still vividly remembers his mother’s justification: “This is morally the right thing to do.”

At school, Hogue had many “rough” days, some involving physical altercations. “When I look back I think, ‘Wow, what a unique perspective that provided me the chance … to have the mirror flipped and for me to be the minority for any period of time,’” Hogue said. “I think that maybe even subconsciously led me to some of these civil rights issues, and so I’ve tried to use that as best I could to help this organization.”

In late 2011, the Corps began implementing the Defense Department’s repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell.” The policy allowed gay men and women to serve, but only if they didn’t tell anyone about their sexual orientation. Prior to that, gay people were banned entirely from serving. From the end of World War II to the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” more than 11,000 gay and lesbian service members were stripped of their honorable discharge status and veterans benefits if outted in uniform.

“We were banging heads behind the scenes on those issues,” Hogue said. “It wasn’t clear how the Marine Corps was going to break on that. … There were a lot of voices inside the senior staff … who were willing to accept old ideas about this.”

But ultimately, after the Corps surveyed the force, Hogue’s legal recommendation was simple: The generation of young men and women inheriting the Corps want a more inclusive and diverse rank and file. Embrace the repeal.

As gay and lesbian service members began serving openly in the Corps, Hogue leveraged the momentum to advocate for opening combat roles to women Marines.

“As a civil rights attorney I knew it was next,” he said. “It’s incumbent on those who lead the organization to create the possibilities of success for women and African Americans in the Marine Corps.” But by arguing for a more inclusive Corps, Hogue knew he would face an uphill battle. Gender integration would also require Marines to address cultural issues. “Some of it’s horrifying,” Hogue said, pointing to instances of hazing, discrimination, and sexual assault. “We’re training young men and women to go out and do really, really hard things. … Sometimes, a sickness creeps in.”

Hogue’s gender integration efforts began with recruiting Capt. Kelly Repair, a young Marine attorney with trial experience in cases involving drugs, sexual assaults, and murder. He immediately brought her into his meetings in the legal library alongside the Corps’ most senior officers. The rules were simple: Rank stays at the door, and only the strength of an idea matters.

“When she got into this, she at first was very reserved,” but Repair eventually “dropped the gloves,” Hogue said. “She saw when the water was rushing around us at 90 miles an hour. To be a part of the effort to channel that water in a more productive direction. As a young woman, my hope was always that that would be like a powerful experience for her.”

By the time Repair joined the team, thousands of women Marines had served in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan. Dozens were wounded. Many were killed. Women like Maj. Megan McClung, Cpl. Ramona M. Valdez, and Lance Cpl. Holly Charette.

“Early conversations where opinions were voiced were draining,” Repair told The War Horse. “Lots of men took a back seat, but not Mr. Hogue.”

Together, the two visited the Corps’ coveted Infantry Officer Course and led the launch of a makeshift all-woman infantry unit to begin gathering performance data. In total, more than 100 women of varied ranks from across the Corps volunteered to participate.

“These young women weren’t trained as infantrymen,” Hogue said. “They did beautifully.”

By 2013, the preliminary data was rolling in positively, and Hogue watched as Marine Corps leadership began to recognize that some women could excel in the infantry. He used the momentum to then convince leadership to hire a university to conduct a study. “My opinion was that if you didn’t have peer-reviewed results, no one would accept our study,” Hogue said. “We should go for the gold standard.”

Despite being the least experienced Marine at the table, Repair forged a reputation for being objective and, as she described it, having “a more open perspective” on what it takes to be an infantry Marine. Each day, she was driven by a desire to make the Corps a better place for women Marines, particularly the enlisted, she said.

“The Marine Corps is a very hard and lonely place to be sometimes,” Repair said. “I know that a lot of other female Marine Corps officers share this position, that my toughest day in the Marine Corps … is easy compared to what enlisted females have to deal with.”

That same year, Hogue and Repair watched as 15 enlisted women attended the School of Infantry. Following 59 days of training in eastern North Carolina, on Nov. 22, three women graduated—Cristina Fuentes Montenegro, Julia Carroll, and Katie Gorz—and earned the coveted title of Marine “grunt.” That evening, Repair and Hogue celebrated, proud of their shared accomplishment, she said.

“Seeing something that you knew from the beginning was possible and then actually seeing it happen was incredible,” Repair said. “The Marine Corps didn’t shut down. … The world didn’t end.”

Over the next two years, the Corps continued to study the performance of women in combat arms specialties.

As the sun set on Sept. 17, 2015, Hogue stood in the hallway of the Pentagon with then-Commandant Gen. Dunford after a day of meetings. Following years of research, the Corps would request an exemption from women serving in infantry roles. The Marine Corps would be the only service to ask to continue the ban on women serving in some combat roles. Hogue could see the struggle on Dunford’s face, he said.

“When people found out that he was requesting an exception, he knew that that was going to hurt some people that had faith in him, and he didn’t want to do that,” Hogue said.

Gen. Dunford, who led Marines in countless firefights, worried that politicians would force the Corps to lower its standards to serve in ground combat roles. “He didn’t want that to happen because he didn’t want to lose Marine lives because somebody made bad decisions.”

Ultimately, in late 2015, the Corps’ request for an exemption to gender integration was denied. Over the coming months, multiple women attended Marine Corps infantry schools. On March 23, 2017, Pfc. Maria Daume, a Russian immigrant who was born in a Siberian prison, became the first enlisted woman to graduate from the School of Infantry and serve in the operating forces. Five months later, on Sept. 25, 2017, 2nd Lt. Marina Hierl became the first woman Marine to graduate from the Infantry Officer Course. Fewer than four years later, Hogue helped the Corps accomplish another milestone in gender integration by welcoming the first class of women recruits to boot camp at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, which historically had trained only male Marine hopefuls. On May 6, 2021, more than 50 women Marines graduated. The women were recognized for winning the final drill competition and for achieving the highest physical and combat fitness scores.

“Marines don’t back away from a fight,” Hogue said. “These women are putting in the work to be a part of this gun club. … That has been a privilege to witness and be a small part of.”

For Hogue, who is nearing the end of his tenure with the Corps and is transitioning to a senior position in the Department of the Navy, the next challenge will be to improve the military justice system.

“I don’t care what anyone tells you. There is no system of accountability for senior uniformed lawyers,” Hogue said. “It is a tightly controlled system under the management of senior uniform guys who do not share power, who do not have any fear of any other authority stepping in … and who basically do what they want.”

Some of the legal system is built “for reasons other than justice,” Hogue said. “It’s been in reform for a number of decades, but there are other systemic problems that just won’t be obvious to nonpractitioners. … It’s too much of a cylinder and anything we can do to break the top off of that cylinder or to allow fresh ideas to flow through … can only improve the output.”

The problem is management, not talent, Hogue said. “Having a group of attorneys grow up inside that cylinder is not the best way to develop a mindset that will drive on the justice that you want to see. …The American public and others are not so ignorant or foolish that they can’t see when a system is flawed, and that is the basis for the lack of trust.”

As counsel for six commandants, Hogue said their thoughtfulness and willingness to address civil rights issues like gender and military justice in uniform has been exceptional.

“All of them have these incredible features that the average person just doesn’t ever get to see, and they’re all different, but they all bring some incredible strength,” Hogue said. “One of the great things about this job is that it’s an enormously privileged opportunity to be at the table and see how they work and at times influence how they work. And that is the great thing about this job. … There really is a huge chunk of what it means to be in the military that the average civilian is just never going to get exposed to. And so we’ll never fully appreciate why those things are important.”

The End of an Era

For more than two decades, Hogue has looked out the windows of his office at an evolving Arlington landscape. Looking out that window, he called his mother the day before the attack, excitedly watching as then-President George W. Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld took off from the helicopter pad just yards away. Just moments before the attack, watching from the same window, he wondered why the Pentagon—in the direct flight path of the airport—was not being evacuated. Moments later, that blast-proof window saved his life.

The next year, when Hogue moved back into his office, he again found himself by that window, wondering how he survived, wondering what would come next.

When Hogue was promoted to senior counsel, he moved into his boss’s office. Just one window down the hall. Same view. By that window, Hogue often reflected on his mentor, Peter Murphy, and how to this day, he strives to live up to Murphy’s legacy.

“He didn’t have to be cutthroat or backstabbing,” Hogue said. “There was a kind of reverence for him in headquarters Marine Corps that was very well deserved, and very much not understood. … More than anything else, he had earned the trust of the senior staff and the junior staff. It wasn’t just the generals who came to see him for trusted advice.”

As the years passed, through Murphy’s window, Hogue watched as the Corps and the Pentagon complex transitioned to fight a post-9/11 war. It began with the destruction of the Annex, the building that was the home of Marine leadership during the wars that forged its legacy, and where the longest war the Corps has ever fought was designed. Then came the construction of the Air Force and 9/11 memorials. And at the center, a view of Arlington National Cemetery, a silent reminder of service and sacrifice amid corporate sprawl and a churning military machine.

From his window, Hogue has reflected on the beginning and end of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the complexities of the world, and the future needs of the Corps. And as troops withdrew from Afghanistan, the memories of service and sacrifice remained vivid, unlike the helicopter pad, battered and faded by decades of weather and sunlight, that rests feet below Hogue’s window. A physical snapshot in time. A constant reminder of how an explosion changed it all. Of a time before the forever wars. Before America launched another endeavor that would bury thousands of America’s sons and daughters.

The men and women he grew to love.

Two decades later, Hogue still feels like he’s working in Murphy’s office—looking through Murphy’s window. And 20 years on, Hogue still works through not only the trauma of 9/11 but the burden of leadership he has shared with the Corps’ most powerful Marines.

“My gut tells me that my continuing devotion to this work is related in some sense to my unwillingness to either address what’s already happened or to move on from it,” Hogue said. “Whether I’m avoiding dealing with it or I’m dealing with it by holding on to it, I’m not really sure. But either of those is plausible. … I’m worried about losing the opportunity to do things that matter.”

Throughout his three-decade career, Hogue has worked grueling hours and traveled around the globe to help the Corps’ leadership navigate the complex intersection of war and the rule of law. And through the past six commandants, he has been a vital thread in the fabric of the Marine Corps.

“There’s always a fire to put out,” Hogue said. “The job definitely takes a toll on you.”

But those demands extend far beyond the Pentagon. Throughout his career, Hogue has missed holidays, birthdays, and time with his wife, Cheryle. The first high school basketball game of his son, Ryan. The induction to the Junior National Honor Society of his daughter, Samantha. “I’d like to think I have an appreciation for the sacrifices that people make,” Hogue said. “I think if I had walked away, I would’ve missed something important in my life.”

In June of 2021, Hogue drove home for dinner with his wife in the same home they’d lived in together since before the attack. He walked through the same foyer. Down the same hallway from which his son, now 32 years old, had stared at him when he came home covered in ash. When he sat down with his wife of 33 years, he told her he was retiring, that he was ready to write his next chapter, maybe work for a private firm or a civil rights organization. Or maybe do nothing for a while. He even wondered about writing a book. They talked about vacations and about what life would be like beyond the Marine Corps.

A week later, unbeknownst to his wife, Hogue accepted a senior position as the principal deputy to the assistant secretary of the Navy for Manpower and Reserve Affairs. In his new position, he will be responsible for the implementation of upcoming reform to the way sexual crimes are handled in the military, but more broadly, Hogue will be in charge of shaping the future of civil rights in the Navy and Marine Corps. But with the increased responsibilities comes a more predictable schedule, limited travel, and more family time: a slower off-ramp to retirement, another chance to serve.

On July 29, during his final weeks as the counsel for the commandant, Hogue walked through the National Museum of the Marine Corps, a building he saw through its inception, construction, and expansion. Hogue walked through the hall dedicated to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and past an exhibit highlighting the first enlisted infantrywoman. He then, for the first time, walked into the section of the museum dedicated to the attack he survived. He stared at a cornice stone from the Pentagon. Then a melted telephone. A fractured metal beam from Ground Zero. A clock frozen in time by the blast. As Hogue focused on each item, his mind kept going back to that day in his office, he said. He saw the smoke fill the room, inch by inch, as they fought to pry open their office door. He felt the blistering heat from the fire burn his skin and lungs. He remembered the fear of death.

As Hogue spoke, his gaze locked upward, and he smiled. Above the display hung a glass case with a bright white frame. Inside was the Marine Corps flag rescued from his office.

“It looks cleaner than I remember,” he said, as he laughed. He pointed out its singed corners and soot, seared into its fabric like the memories in his mind.

As Hogue examined the flag, he talked about how, over the last two decades, he has learned the Corps isn’t just a branch of the military, but a body of people, each of whom are represented in its cloth. The emblem at the center—an eagle, globe, and anchor—represents Marines past and present, he said. The red honors the blood of the Marines and corpsmen who were wounded or killed. And the gold fringe, the civil servants who serve alongside them. He talked about how much his time with Marines and sailors has meant to him, and that while he didn’t earn the title of Marine the traditional way, the Corps became his family, and the Marines he served alongside embraced him as such.

For the 20th anniversary of the attacks, Hogue will look out his window one last time before he walks through the doorway that once separated life from death. But unlike his escape decades ago, Hogue will leave his office with clarity. And while he says he may never truly be at peace with the events of Sept. 11, the sacrifice and trauma has led to a rewarding life of service.

“It’s a presence in my life,” Hogue said. “It just is. …It never goes away. It’s something I’m always going to try to understand, but I’m not pushing back on it anymore. I just have to accept that it’s part of my life and that I just can’t solve the puzzle. … That the war’s not over.”

This War Horse feature was published in partnership with PBS Newshour. The story was reported by Thomas J. Brennan, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Ben Kalin, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Videography was produced by Julian Lim and Daniel A. Nelson. Audio was produced by Elena Boffetta and Kimberly Cataudella. Photographs were taken by Eliot Dudik. Prepublication review was completed by BakerHostetler.