The Army has kicked off a study of the service’s current height and weight requirements, which could eventually end in a change to the standards for the first time in decades.

Questions about changing the height and weight requirements have been brought up regularly to Sgt. Maj. of the Army Michael Grinston as he’s visited soldiers at various installations over the last several months, Grinston said last week at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The standards haven’t been reviewed in roughly 30 years, and Grinston admitted that while he originally thought soldiers were asking to “get bigger,” he found that what they were really asking is, “Do we have the height and weight tables right?”

“The rationale is, it was time to go look at it,” Grinston said. “What technologies do we have today that didn’t exist 30 years ago? There’s a lot of new technology, but can we afford it? Is it better or worse? We don’t know. That’s the whole point of the study.”

The Army’s study, which is being conducted by the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine and Army Center for Initial Military Training, was first reported in July and began at Fort Bragg on Oct. 18. Officials said last week that they expect it to take roughly six to nine months before changes can be recommended to senior Army leaders.

Currently, Army Regulation 600-9 gives soldiers a table that tells them how much they can weigh based on their height, gender, and age. A 22-year-old male soldier who is six feet tall, for example, can weigh up to 195 pounds. A 19-year-old female soldier who is five feet tall can weigh up to 128 pounds.

But soldiers have said the existing standards are outdated and don’t account for changing body types, especially considering it’s based on body mass index, a scale that was created roughly 200 years ago and which experts say is inaccurate.

The voluntary study at Fort Bragg is designed to see if there’s something to that critique, and whether the old metric should be changed. Soldiers on active duty, in the Army Reserve, and National Guard can volunteer to have their body composition measured through four different methods as part of the study. Those methods include a full body DXA scan, which is considered the “gold standard in the industry of health and fitness,” according to Matt Bartlett, the project manager for the study. The DXA scan collects data on things like muscle mass, fat mass, and bone mineral density.

“Another reason why we consider it the gold standard is because it’s very precise on many different levels and has very minimal human error,” Bartlett said. “For a lot of other measurement techniques, especially taping, it can have human error and that sort of thing. This has been around for 20-30 years now and has really stood the test of time.”

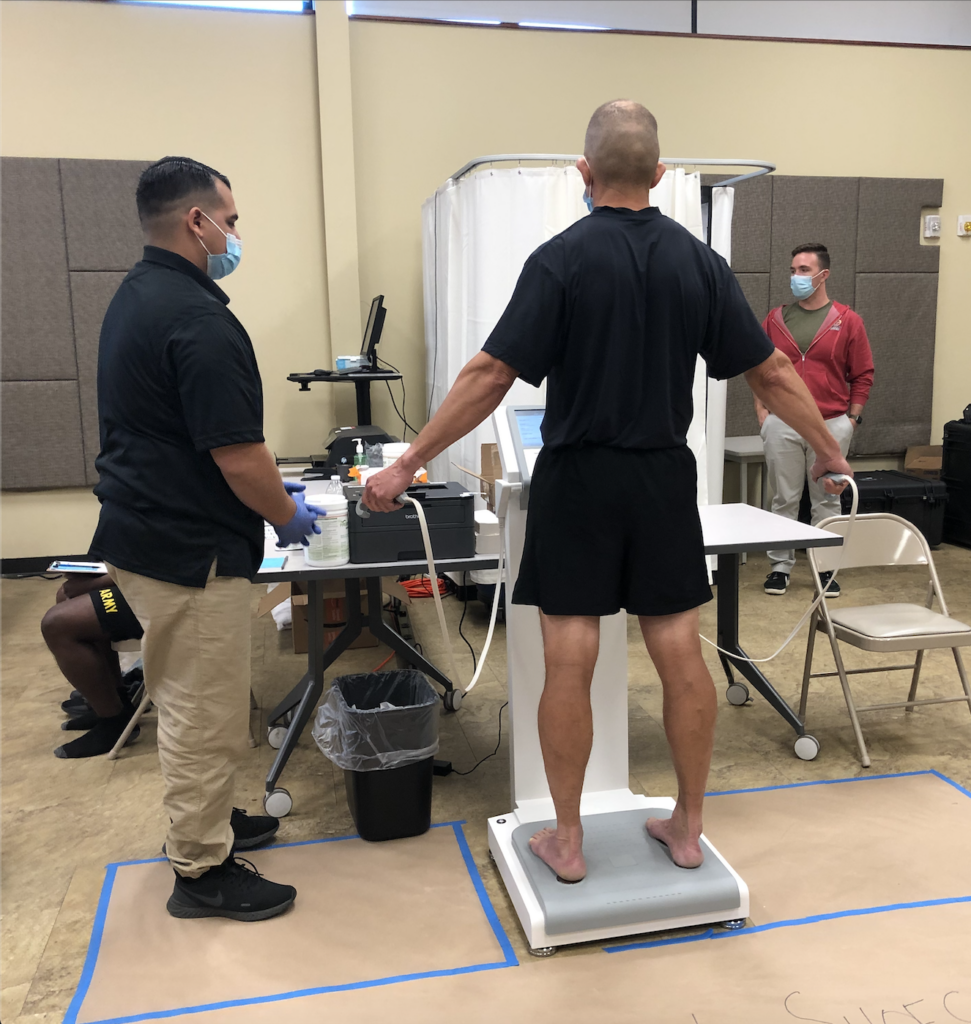

Soldiers who volunteer will also use a three-dimensional body scanner that uses infrared lasers to collect over 2 million data points in 13 seconds that results in roughly 200 to 300 body measurements. They’ll also go through a bioelectrical impedance analysis which sends “a very, very low voltage electrical signal through the body” to measure things like muscle and fat mass.

Of course, there will also still be a good ‘ol fashioned tape test.

The tape test, which is used to measure a soldier’s body fat to see if they meet their table weight requirement, has been criticized by soldiers and experts as inconsistent and inaccurate. A common complaint about the tape test is that there’s too much room for human error. One Army major told Task & Purpose in August that when soldiers go to get measured it’s “potentially about to end your career or start the downfall, and it’s all dependent on how this person is going to tape you.”

The measurement could vary based on how the measuring tape is positioned, the major said, or how tight someone is squeezing the tape, or how the person measuring you might have you stand. There are even some tricks soldiers have adopted to get the measurements they need.

“If you can get your neck bigger and your waist smaller, then you’re giving yourself every possible advantage,” the major said.

Grinston, who attended the second day of the study at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, last week, saw differences in his own measurements based on which method he was using. The highest measurement he got was 17% body fat, and the lowest, from the tape test, was 11%.

“That’s a big range if you really look at it,” Grinston said. “I like 11, but I don’t think I’m actually 11% body fat.” Later that day while talking with reporters, Grinston also acknowledged the concern of human error when it comes to the tape test.

“I think there’s always a human factor in the tape test, and it could work for you or against you. We try to mitigate that with minimal training … but I think whenever there’s a human and we do this across the force, there’s always going to be some variance,” Grinston said, adding that the tape test is “very cost effective for the Army” and that by the end of the study the tape test could still remain as a method the service uses. He said the study could recommend that soldiers get a tape test, but then retain the option to go have their body composition measured elsewhere if they don’t think the tape test was accurate.

While the first part of the study is being held at Fort Bragg, Army officials said it could be expanded to other installations and soldiers depending on what kind of data they get from Fort Bragg. If they don’t have enough women in a certain age group to volunteer, for example, they’ll continue conducting the study elsewhere to get the amount of data they need from that demographic.

In addition to looking at body measurements, the study will look at soldiers’ physical fitness test scores, any injuries they may have, and any pregnancies and childbirths for women.

Soldiers who’d volunteered for the study on Oct. 19 told Task & Purpose they were excited at the possibility of a change to the Army’s height and weight standards, especially considering how long the tape test had been used.

“It’s an old system that they’re using, the taping and everything,” said one Army infantryman, Spc. Alex Watkins, who added that he hoped the study brought “more accurate results” to the Army’s process.

Another soldier, 2nd Lt. Kayla Maupin, an infantry officer, said she could “already tell the variance of the way they’re measuring.”

“I’ve always kind of had that in my head, that the way I was being taped didn’t accurately reflect my potential body fat and muscle mass,” Maupin said. “For me personally, I joined a combat arms profession so I have to prioritize building good muscle mass in order to bear weight for my job, but at the same time I’m slightly worried with the way I have been measured in the past that might affect the scale and affect the way I tape.”

While it’s still unclear whether the study will result in a change to the standards, Grinston encouraged all soldiers to participate — especially those who feel their body type isn’t typically represented in the Army, or who have run into problems with the existing standards.

“We actually need people that didn’t pass the body composition tape test that we have now, and it would be helpful to see, but did they pass the [Army Physical Fitness Test] or the [Army Combat Fitness Test?]” he said. “That’s why it is comprehensive, and we don’t just need all the young, fit soldiers that pass. We actually need all shapes and sizes.”

More great stories on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.