Editor’s note: This article contains graphic descriptions of combat.

Heidi Henry was alone in her office on Feb. 24 at the rural Pennsylvania high school she works at as a school nurse when she got a call from an unknown number.

On the other end of the line was a soldier, identifying himself as someone who worked for Michael Grinston. Grinston — the top enlisted leader of the U.S. Army and right-hand man to its top general — wanted to speak with her, the soldier said.

Henry was shocked. She had left the Army as a specialist almost a decade before, having served just over five years as a combat medic. She hadn’t seen or spoken to Grinston since August 2012 in Baumholder, Germany, when he was her command sergeant major in the 170th Infantry Brigade Combat Team. Now his staff was calling out of the blue because he wanted to chat.

When she finally connected with Grinston, it was “instantly like talking to an old [non-commissioned officer],” Henry said. They caught up briefly, talking about their families and where they were in their lives. A lot had changed, and while he did want to catch up with her, it wasn’t the main reason he’d called.

Instead, her former sergeant major wanted to ask about her experience during a 2010 deployment. She deployed with Grinston’s platoon to Afghanistan in February of that year, and was the only woman in the unit, at a time when it was uncommon for women to serve in ground combat units. And during the deployment there were times when she was the only woman anywhere, and there weren’t things like restrooms or showers or separate facilities for women.

Grinston had good reason to be curious about Henry’s experience: since taking the job as the top enlisted leader of the service, he has been urging leaders to embrace a people-first culture in which every soldier is treated as a valuable member of the team. And for months, he’d been using his deployment with Henry as an example of what right looks like. As far as he remembered, she had been valued and treated with respect during that deployment by the men in their unit. But he had never actually asked her about it.

“You know, I look back [on This is My Squad] and … I’m like well, maybe I screwed this up,” Grinston told Task & Purpose. “I never asked her. I said, I think I should ask her. I want to know. I want to know, am I wrong? Did I miss something? Did I screw this all up? I’ve been talking about if you just treat people the way they need to be treated, and you treat them like they’re a part of your team and your squad, they’ll be protected. And I’ve really believed that my whole life, but I just didn’t ever ask.”

In fact, Henry’s experience was just as positive as he’d remembered it to be. It helped that she was deploying with the command sergeant major; her deployment was “so different from all the other medics,” she said, “because of the opportunity I was given to work with him.”

Looking back on that deployment, Grinston recalled hearing that the medic deploying with them was a woman — the only woman in the unit, in fact — and he went in front of his soldiers to issue a warning. “I just want to make sure everybody’s clear: If anything happens to her, I’m going to take it like you did something to my daughter,” Grinston said.

“Really makes sense now when I think about all the places we visited and all the patrols we did,” Henry said. “He always had my back.”

Grinston has been one of the most publicly visible Army leaders over the last two years. Throughout his tenure he has overseen significant cultural changes in the country’s oldest military service, such as extending the timeline for postpartum women to meet Army fitness standards, after research showed women need longer to recover from childbirth than the Army was providing; changing hair regulations from a standard that often forced women of color to damage their hair and scalps to meet it, and which made it difficult for gear like helmets to fit properly; and launching a review of height and weight standards following an outcry from soldiers about the outdated body mass index system the Army currently uses.

But who is Grinston, and what drives him? His official Army biography will tell you that he has held “every enlisted leadership position in artillery” and has completed “all levels of the non-commissioned officer education system,” including Ranger School, Airborne School, and Air Assault School. But he’s much more than that: he is the “epitome” of the Army’s non-commissioned officer corps, who didn’t believe he’d survive his first deployment to Iraq, let alone his second. He’s a dedicated husband and father to two daughters, as well as a die-hard Alabama football fan. He doesn’t watch war movies and he loves books by Malcolm Gladwell. Lately, he’s been quoting a lot from Upstream by Dan Heath, a book about preventing problems before they happen, in discussions on military sexual assault and suicide. He can’t stand incompetence, he rarely misses PT, and he’s not a bad golfer.

What his official biography won’t tell you is that he has seen the very worst of combat through six combat deployments, earning him five Bronze stars — two with valor devices that are still difficult for him to talk about, that he would give back in a second in return for the soldiers he’s lost. It doesn’t tell you that most of the time, you’ll find him wearing the 1st Infantry Division combat patch in remembrance of those soldiers he lost on his first deployment to Iraq.

Reflecting on his service, Grinston says now he may have been too hard on his soldiers throughout his career, had too high of expectations, was too demanding. Some of his soldiers would probably say he was an asshole. But you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who wouldn’t be able to recognize one indisputable fact: Grinston lives and breathes the Army.

“In our line of work, you go to war with whoever happens to be on your team at the time,” said retired Army Gen. Robert Abrams, a career Army officer who is the third in his family to earn four stars. “But all of us have a short list of hey, if we ever got called out, who were the four or five people you would take with you on your team? He’d be on my team.

“If I had four picks, he’d be one of them. Without question.”

‘I did my best to bring everybody back’

The Army wasn’t in the plan for Grinston. Not originally, anyway.

In 1968, he was born to a Black father and a White mother. When he was three years old, his parents divorced and he moved with his mother to Jasper, Alabama.

Alabama was one of the states most opposed to the Civil Rights movement at the time; Gov. George Wallace, a fierce opponent of the movement and school desegregation in Alabama, had just won his second four-year term. It was just five years after the Alabama Senate passed legislation forbidding school districts from providing their plans for racial integration to the federal government.

It was undoubtedly a challenging time and place for a bi-racial boy to grow up in.

“Racial identity is something that I have struggled with my entire life. … Sometimes in my life, I felt like it’s in the movie ‘The Green Book’ where the actor gets out of the car and he says, ‘I’m not Black enough for the Black people, and I’m not White enough for the White people,’” Grinston said in a video he posted to Twitter last year, revealing to many who had no idea that he was half Black.

Grinston learned the self-discipline that many of his soldiers remember him for at a young age. His mother taught him to be respectful and disciplined, and being raised by a single parent, it was her way or the highway. He originally planned to be an architect since his whole family worked in construction — and even got accepted to the architecture school at Mississippi State — but he ran out of money, and decided to enlist in the Army.

His mother had doubts. “You’ve got a terrible temper,’” he recalled her saying. “‘You’re never going to make it.’”

“I thought she was right,” Grinston said.

But in 1987, Grinston enlisted as an artilleryman. He went to basic training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he was immediately chosen as the platoon guide, a recruit chosen by the drill sergeants as a kind of liaison between the training cadre and other recruits. He remained the platoon guide throughout his entire time in basic training, something that he didn’t realize at the time was unusual.

The discipline he’d learned as a child stuck with him as he graduated training and went to his first unit at Fort Lewis (now Joint Base Lewis-McChord) in Washington. He did his best to do exactly what he was told and be exactly where he needed to be, when he needed to be there. He decided to re-enlist after his first term and moved to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, which was closer to home.

The problem was, he was rarely actually at Fort Campbell; the moment he arrived he went out to the field, then he was sent to Ranger School, then Air Assault School, and then he deployed during Desert Shield and Desert Storm from 1990 to 1991.

Still, he didn’t expect the Army to be a long-term career choice. He was accepted into Mississippi State’s architecture program a second time, and had plans to leave the Army after that deployment. The Army, however, had other plans.

In 1992 he was stationed in Germany, where he met his wife, and then it was one thing after another that kept him in uniform. He stayed there for three years before going back to the U.S. and being assigned to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in 1996. Since then he has been all over the map: In 1997, he became a drill sergeant at Fort Sill; the Army then sent him to Italy, then to Germany, back to Fort Bliss, Texas, up to Fort Drum, New York, on a rotation through Kosovo in 2002, and in 2008 back to Germany.

And while much of Grinston’s motivation over the years stems from his belief and desire to be with and help soldiers, that doesn’t mean his soldiers always liked him. In fact, Grinston admits that as a drill sergeant, he “was the devil.” (That belief among his soldiers wasn’t helped by the fact that he was assigned a phone number that included “666” on three different occasions.)

“I was mean,” he said. “There’s no way I could lie to you, if you were to talk to my soldiers … I was not nice, I was not fun. I wouldn’t want me as a drill sergeant.”

That’s not all there is to it, of course. Soldiers who have served with him described him as technically proficient — impressively so. Someone who could “disassemble, reassemble, function check a .50-caliber machine gun like he was starting up his weed wacker,” according to Mike Lavigne, a retired Army sergeant major. A seasoned enlisted leader who was “the first to salute” a brand new lieutenant despite the obvious gap in experience between them, said Dave Alvarey, a former platoon leader who deployed with Grinston in 2004.

He was someone who followed the standard to a T, and expected all of his soldiers to do the same. If a soldier didn’t run fast enough, they’d run more until they did; if they didn’t load a Howitzer fast enough, they’d do it again, and again, and again. His former battery commander, Nathan Fischer, recalled Grinston telling soldiers to do extra push-ups and pull-ups because they had started walking away from their morning workout at 7:28, two minutes before the 7:30 end time on the training schedule.

Brendan Dignan was a brand new second lieutenant when he first met Grinston in May 2002. He had just joined his unit in Kosovo, and recalled one morning when he and the other lieutenants were sitting around in their barracks. Suddenly the door “flew open,” Dignan said, and Grinston was standing in the doorway.

“Gentlemen, what are you doing?” Grinston said to the lieutenants. They asked him who he was since they had never seen him before.

“I’m your new first sergeant,” Dignan recalled Grinston saying before he ushered the new officers out of their living quarters towards morning PT. When they told him that they, the lieutenants, did PT on their own time later in the day, Grinston responded simply: “No, you do PT now, with the soldiers.”

Fischer said Grinston’s arrival as the battery’s new first sergeant was a “really big change” for the unit because of his high standards. “People learned that it was kind of his way or his way,” Fischer said. But those expectations resulted in their unit becoming one of the top-rated in the battalion — whether it was PT, or a gunners test, Grinston wanted their battery to be the best.

The relentless focus on training that Grinston had when he was just a young soldier grew into his way of protecting his troops, too. He figured that he may not be able to prevent them from getting hurt or killed on deployment, but he wasn’t going to lose someone because of a lack of training.

“I think I did my best to bring everybody back,” Grinston said. “I didn’t, but I think they knew that I truly cared. And when I made them run a billion miles — when you’re in combat, you didn’t fall out.”

Less than a year after the war in Iraq began, Grinston deployed to Iraq for 13 months as the first sergeant of Charlie Battery, 1st Battalion, 7th Field Artillery Regiment. The battalion became a mechanized infantry battalion, and Charlie Battery — which became Charlie Company — performed “so well” during pre-deployment training under Grinston that they were made the tip of the spear for the battalion in Iraq.

While that was a testament to their discipline and training, it also meant that Grinston’s company “had the most losses and the toughest time,” said Kyle McClelland, the commander of 1st Battalion. Indeed, whenever McClelland went out with Grinston’s company he “found trouble.” Twice, he was blown up by roadside bombs and got into a firefight with Grinston close by. “Hey I’m not going out with you anymore,” he later recalled telling Grinston. “Everywhere we go, we just get shot at or blown up.”

Grinston has been shot at and blown up repeatedly. Rocketed, and mortared, too. Perhaps the only thing he hasn’t been through, he said, is a nuclear blast. And being “the most shot-at person in the entire battalion” is not exactly a badge you want.

“It even came up at one point, like ‘First sergeant, the men are starting to talk, you’re like bad luck,’” Grinston said. But in reality, he said he chose to be on every mission that had the potential to go sideways. If he was going to send his soldiers into a high-risk environment, he figured, he should be there alongside them.

“It was just me going where I thought would be a dangerous mission … just to protect as many as I could,” he said. “And if I was going to put them in harm’s way, by God I was going to be with them.”

That perspective is what found him on a patrol on April 9, 2004. It was just around two months after the unit arrived in Baiji, Iraq, when Grinston and the company commander were at the local police station with Alpha Platoon. They were on the north side of town, according to Alvarey, the platoon leader at the time.

Alvarey was standing on the top of the building, talking with other soldiers in the platoon, when the platoon sergeant announced they were leaving. Iraqi policemen had told their company commander that there was “some sort of insurgence presence” at the mayor’s office, which was roughly 10 blocks south of where they were.

They assembled a squad of around 12 soldiers and started moving towards the mayor’s office. It was eerily quiet as the soldiers slowly made their way down the street. At one point, Alvarey looked down an alleyway and saw a kid running in the opposite direction. “It was kind of a weird thing,” he said. “Like, this is odd.”

Up ahead, Alvarey could see Grinston near the front of the group of soldiers as they came to a main street in the city. They started crossing the street, one by one, under the cover of other soldiers, when suddenly Alvarey was engulfed in a cloud of smoke and dust. Enemy insurgents had fired two rocket-propelled grenades at their position. Two soldiers were killed instantly and one was seriously injured. One of the soldiers’ bodies was blown into pieces by the blast, McClelland said, and for a few moments they couldn’t find his head.

Hit with shrapnel in the leg, Alvarey was confused. He hadn’t seen what transpired because it happened so fast. He thought maybe they’d set off an improvised explosive device.

Soldiers immediately began firing back at the enemy and a vicious firefight ensued. Alvarey recalled shooting his rifle next to Grinston’s head, not realizing how close he was to Grinston’s ear. “I wasn’t thinking about it,” Alvarey said. “And he looked at me and was like, ‘What the [fuck] are you doing?’”

They were pinned down for at least 15 minutes before other soldiers arrived in Humvees and got them out. “Grinston stayed there until he got every piece of military equipment, every piece of a body,” McClelland said. Alvarey remembers being in one of the first Humvees with the unit’s medic as he died, and looking back to the last vehicle, seeing Grinston.

“I recall looking back and seeing him being the last one on the ground,” Alvarey said of Grinston. “Picking up the soldier and putting him in the Humvee … kind of looking around, basically doing a search of the ground to make sure everything was taken care of. He takes the Ranger Creed to heart, you know? He would certainly rather die than leave a fallen soldier there. Not even a debate.”

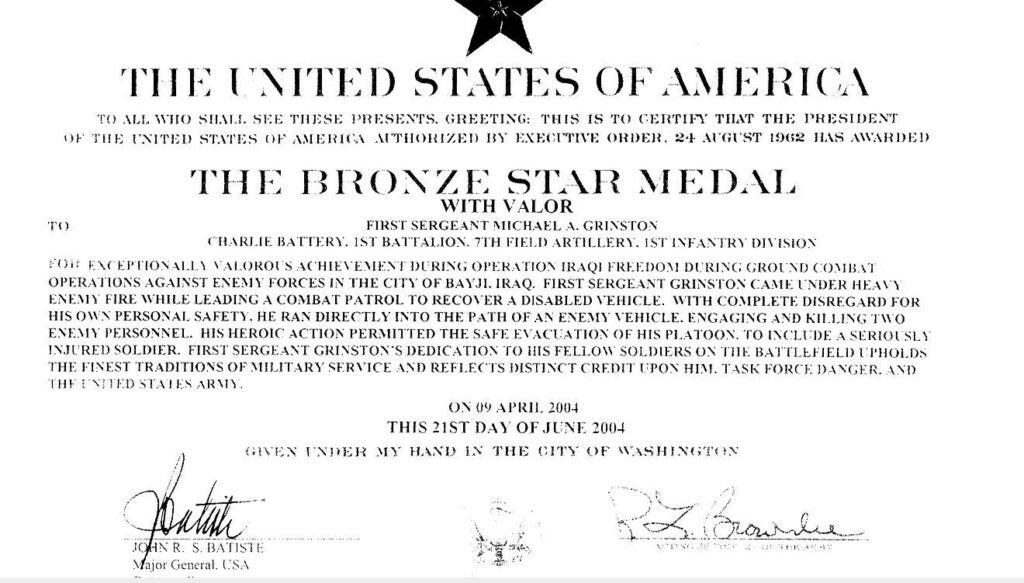

Grinston received his first Bronze Star medal with a “V” device distinguishing him for valor during that firefight, and a second just three months later when his unit was caught in a five-hour battle, pinned down by RPG, small arms and sniper fire.

“After assaulting through enemy fire, he mounted a counterattack and defeated the enemy, resulting in 10 anti-Iraqi forces killed and 10 anti-Iraqi forces wounded, with no friendly casualties,” the citation for the second Bronze Star says.

But the day that lives in his memory and that of the company is April 9, 2004. It’s “the day that our unit remembers,” Dignan said, because of the sudden loss of three soldiers, Staff Sgts. Toby Mallet and Raymond Jones Jr., and Spc. Peter Enos. Dignan wasn’t with them that day, but he remembers clearly seeing Grinston and the others return to base. “It was almost like seeing someone that worked in a butcher shop,” he said. “His entire uniform was just full of blood.”

Discussing that day is painful for Grinston. He rarely even talks about it, but it’s impossible not to remember.

“I got an award and I don’t even know if I deserve it,” Grinston said quietly. “I’d give it back in a second if I could get the soldiers back.”

‘I really don’t want to be Sgt. Maj. of the Army’

Becoming the sergeant major of the Army was not in Grinston’s plans after seeing the kind of combat he did. To do that, he’d have to live through each deployment, and he wasn’t so sure that would be the case.

“It got to the point that by the time I’d gotten to my second deployment, I’m like, there’s no way,” Grinston said. “There’s no way I could get out the first time, I’m definitely going to die on the second and third. We were in Mahmoudiyah — Triangle of Death. Great.”

By that point, Grinston had been deployed for 13 months from 2004 to 2005, had just a few months with his family before leaving to attend the 10-month long Sergeants Major Academy at Fort Bliss, graduating early in 2006, before going back to Iraq later that year for another 15 months. During that 15-month stint, this time with the 10th Mountain Division, Grinston submitted his retirement paperwork. If he lived to the end, he thought, that would be it. He’d seen enough and frankly so had his wife, who sat next to him during the dozens of memorial services for soldiers killed in combat.

Yet he decided to stay in, mostly due to the lobbying efforts of the 10th Mountain Division sergeant major who refused to accept Grinston’s decision. He called “every day,” Grinston said: “I’ve got a job, I’ve got a job, you can do this, just take a break.”

“There was no break by the way,” Grinston remarked dryly. “So if you talk to him, tell him he’s a liar.”

Grinston was eventually promoted to command sergeant major for I Corps, where he was responsible for about 40,000 active duty and reserve soldiers, at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington.

After eight months with I Corps, he was chosen as the command sergeant major for U.S. Forces Command, the Army’s biggest largest command composed of more than 750,000 soldiers.

Serving at FORSCOM was the first time it even crossed his mind that sergeant major of the Army could be a possibility. And as it turns out, he partly has his old boss to thank for that promotion.

McClelland, Grinston’s old battalion commander, was at the Pentagon when Gen. James McConville was nominated as the Army Chief of Staff. McClelland had worked with McConville previously, and told him he knew just the person he needed by his side as the next chief.

But Grinston wasn’t necessarily jumping at the opportunity. Not at first, anyway.

“Grinston called me and said, ‘Did you have something to do with this? Because I really don’t want to be the Sgt. Maj. of the Army,’” McClelland laughed. “I said ‘Well, you don’t really tell the boss no when he asks.’ …. I think he was kind of worn out.”

Soon after Grinston took office as Sgt. Maj. of the Army — or SMA, as many refer to him — on Aug. 9, 2019, one challenge after another came down the pike. Just days into the new year, paratroopers with the 82nd Airborne Division were deployed to Iraq after a U.S. airstrike killed the head of the Iranian Guard Revolutionary Guard Corps. And soon the Army, and the rest of the military, was adjusting to a new normal as the Covid-19 pandemic swept across the world.

Two of the most challenging moments came halfway through the year: when Army Spc. Vanessa Guillén went missing from Fort Hood, and was later discovered to have been killed by another soldier; and when George Floyd, a Black man in Minneapolis, was killed by a White police officer who knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes, sparking protests throughout the country.

On June 3, Grinston released a joint statement with Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy and Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville. In it, the three leaders said they “[felt] the frustration and anger” and “will continue to protect Americans, whether from enemies of the United States overseas … or from violence in our communities that threatens to drown out the voices begging us to listen.”

“To Army leaders of all ranks, listen to your people, but don’t wait for them to come to you. Go to them,” the senior leaders said. “Ask the uncomfortable questions. Lead with compassion and humility, and create an environment in which people feel comfortable expressing grievances. Let us be the first to set the example.”

Just two days later, Grinston posted a video on Twitter in which he discussed his racial identity, demonstrating his commitment to setting an example. “This isn’t a political conversation,” he tweeted. “It’s a PEOPLE conversation.”

Then in December, the so-called “Fort Hood report” was made public, and the findings from an independent panel of civilians with active-duty military and law enforcement backgrounds about the command climate and culture of the Army’s largest base in Fort Hood, Texas, were dismal. The report was “deeply personal” to Grinston, according to McCarthy, especially in what it said about the non-commissioned officer corps.

As an NCO himself, he was “profoundly disappointed” with what he saw reflected in the report. One NCO was quoted as telling another soldier that “females are here for our entertainment.” Another believed that women were “sexual objects and ‘should be at his feet.’”

After reading it for the first time, Grinston wrote three words at the top of the first page: Rage, disappointment, failure. Then he kept writing on nearly every page, and marked sections he found important with sticky notes.

“He’d stayed up all night the day he got it, and read it,” McCarthy said. “And it was hard for him to speak, he was so upset … because the Army is his family. It’s his life.”

Grinston quickly became the most vocal proponent of the Army’s “People First” initiative — launched in response to the report in December 2020 — largely in part because his role is to represent the Army’s enlisted force. McCarthy referred to him as “the conscience of the Marshall Corridor,” referring to the hallway in the Pentagon that is home to Army leadership.

Since then, the Army’s People First Task Force has been studying how best to implement the 70 recommendations made at the conclusion of the report. The recommendations were targeted at fixing the Army’s Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention (SHARP) program, which the report concluded was ineffective and “structurally flawed,” as well as overhauling the Criminal Investigation Division. The civilian panel found that CID was understaffed and under-resourced, which left holes in important investigations.

Meanwhile, Grinston has been working on finding solutions on his own with the help of command sergeants major across the Army. In a break from the Army’s typically-rigid and risk-averse fashion, these informal ideas summits are meant to be a place where enlisted leaders can suggest ideas on how to better take care of soldiers and decrease instances of harmful behaviors like sexual assault and harassment, suicide, drunk driving, and racism.

“Everybody knows why we have this meeting is to actually fix problems inside the Army,” one command sergeant major told Grinston during a recent video call. “We have to set the way forward.”

Notably, one recent meeting featured a sergeant major who had looked for trends in the first 180 days that a soldier arrives at their installation. Within those 180 days, they hypothesized, soldiers were most at-risk for “negative” incidents such as suicide, sexual assault, or even a speeding ticket. Now they wondered whether they should focus more resources on soldiers in those first 180 days, in an attempt to see if it could help them better adjust to a new installation and unit, and potentially stop those negative incidents from happening.

During his presentation, the sergeant major explained to the group that it was too early to tell whether the data they’d collected was having a noticeable impact. Grinston asked the sergeant major if he could see the data, to which he responded that they already had it but that he didn’t include it in his presentation because it’s “just so new.”

“The purpose of this meeting is learning, right?” Grinston said. “I would like to share early … throw in something and fail, it’s okay. We know where we want to aim. So throwing in the data, trying to understand it is great, but what I don’t want to do is wait six months and we’re not sharing what we’re doing across the Army.”

The idea of moving ahead of the data and feeling okay to fail is not typical of the Army; the service typically spends years studying policy proposals before making a change. The hesitancy to share information is partly due to people not wanting to feel like they are suggesting something stupid or useless.

“It’s not perfect because we’re all over the place, and I’m okay with that,” Grinston said. “I told them in the beginning, I said, ‘You know, this problem, we want [perfect] before we do anything. And then we can’t figure out why we’re two years late.’”

That kind of focus on change has won him both admirers and enemies, inside and outside the military. And some of the criticisms he has received took a turn that those who know him find laughable: that he is soft, “woke,” or cares more about scoring political points than leading the Army.

One of the most intense periods of criticism came after Grinston and multiple other Army leaders spoke out against comments made by Fox News host Tucker Carlson. In March, Carlson took issue with “new hairstyles and maternity flight suits” in the military.

“While China’s military becomes more masculine as it’s assembled the world’s largest Navy, our military needs to become, as Joe Biden says, more feminine — whatever feminine means any more, since men and women no longer exist,” Carlson said.

Grinston called Carlson’s words “divisive” and said they “don’t reflect our values.”

“Women lead our most lethal units with character,” he said. “They will dominate ANY future battlefield we’re called to fight on.”

The backlash from Carlson’s supporters was swift. National Interest, a conservative magazine focused on international relations, included Grinston in an article titled, “The Woke-Military-Complex,” in which they identified “sensitive senior military personnel” speaking out against Carlson’s comments. Then in August, Fox News published an article claiming that Grinston was prioritizing “‘diversity amid Afghanistan evacuation,” after Grinston tweeted in recognition of Women’s Equality Day.

Grinston had tweeted in recognition of Women’s Equality Day about an hour before a suicide bomber in Afghanistan killed 13 U.S. service members and scores of Afghan civilians at Hamid Karzai International Airport. Conservative critics of Grinston pounced on the tweet, criticizing him for talking about diversity on the day 13 service members were killed, despite the tweet being sent long before the attack occurred.

“This is where your mind is today bro?” asked Mike Cernovich, an alt-right media personality.

“We have an #AfghanistanCrisis and this is your tweet. Shameful,” said Jessie Jane Duff, a Marine Corps veteran and contributor to Newsmax, a conservative news organization.

Despite such criticism, Grinston has remained one of the most accessible senior leaders to date on social media. He did an “Ask me Anything” session on Reddit in June, and a live Q&A with popular Instagram account, Veteran with a Sign. And Grinston’s Twitter and Instagram accounts are constantly active, often responding to soldiers online who tag him in posts, voice complaints, or ask him questions.

To those who know him, that is the real Michael Grinston — a soldier who confronts things head-on, not some soft leader who is more focused on nail polish than winning wars.

“Pound for pound, I’d put him up against anybody,” McCarthy said of Grinston. “To say that he’s soft, or he’s woke, [these] are people that have no idea what they’re talking about. … I dare you to go into the gym with him or go train with him on a live-fire range. You’d be losing your breath within seconds.”

“I think those sorts of comments come from people whose view of the world is, they don’t value diversity. They would prefer the old status quo, and they’ll look for anything to criticize,” said Gen. Abrams. “But to try to label [Grinston] as some softy… Wow. You couldn’t be more wrong.”

‘I love them, I did all that so that this never happens in my country.’

While Grinston has an office in the Pentagon, it seems he clocks more time on the road visiting Army installations and soldiers around the country than he does sitting behind his desk.

The office, on the third floor of the building, is like other senior leader offices in many ways: a large wooden table, topped with challenge coins; books — lots of them; and a wall of certificates and other achievements from his Army career. He’s not as interested in those though.

He’d much rather tell you about the photos on a different wall, featuring the units he served in, the soldiers he knew, and the commanders he supported. There are photos of him at the White House, from the time he accepted a veteran’s Medal of Honor on his behalf. There’s also a framed composite, on which he’s featured, of Black 4-star command sergeants major. That one in particular is incredibly meaningful to him.

But there’s something else hanging in his office that means the most, and it’s traveled with him since before his time as the SMA. Behind his desk is a canvas painting of a mountain-scape, colored with various shades of blue and purple. Looking at it feels like sitting on a lake before sunrise — serene, calming, peaceful. His daughter, who now attends art school, painted it for him at a time when he was in an office that didn’t have any windows. He has windows now — a perk of being a senior leader in the Pentagon, where windows, natural sunlight, and cell phone reception are a luxury — but he still looks at it when his day gets stressful or difficult.

“That gets its own wall,” he said proudly.

The love he has for his daughters, and for his wife, is palpable. It’s been a driving force for much of what he’s done throughout his career, despite at one point believing that his career could be what takes him away from them. But he prepared for that; before one of his deployments, he wrote a 15-page letter to them, complete with everything he wanted them to know in case he wasn’t there to tell them himself. They’ve never read it — ”I’m not dead,” he stated matter-of-factly — nor have they read any of the multiple journals he wrote during each deployment.

He doesn’t talk about combat with them, and he barely talks about it with his wife. ”I think I’m fairly guarded,” he said. He recalled telling his wife once that if she really wanted to know what his deployment had been like, she’d have to read the journals herself.

“I just can’t tell you,” he told her. “I can’t.”

And while his daughters never had to read that 15-page letter, what he would want them to take away from it is simple: He loves them.

“I’m doing it for them,” he said. “So that they can go to school as a woman. So that they don’t have to wear a burqa, they can wear anything they want. So they don’t have to drive down the road and watch the road explode. So they don’t have to live in a country where vehicles explode and kill 30 people, or hundreds. That’s what I would tell them. I love them, I did all that so that this never happens in my country.”

Despite the many things he’s accomplished over his long career, he seemed to find it surprising that the soldiers who he served with would have overwhelmingly good things to say about him. When he learned that they did, he responded, “I don’t know why.”

He’s not blind to the things his critics might dislike about him — in fact, when asked what he thinks some of those criticisms might be, he had a list of qualities at the ready: he may have expected too much, been too demanding, too harsh; he thinks some soldiers probably saw him as unfair, despite his best efforts not to be; he’s preaching “This is My Squad” now, when he knows he could have been much better at it himself as a young leader. That kind of self-awareness and reflection, of course, is something that comes with time. It’s something that comes from a long career, full of failures and successes and finding ways to grow.

It wouldn’t be strange to think that kind of long career would wear on him, all these years later. In fact, Gen. Abrams said the last time he saw Grinston, it appeared that it had. “He is giving it his all, but it’s a grind,” Abrams said. “I could see the grind on him. He wasn’t his normal, sort of effervescent — he’d been ground off a little bit. And Washington will do that to you. And he’s not immune to it. He’s not giving up one ounce of energy.”

Still, at 53, perhaps Grinston is at least just a little bit tired, just a little bit ready to slow down, if even for a moment.

As we neared the end of our last interview, thinking over all I’d learned about him, I couldn’t help but ask exactly that. Are you tired?

“No,” he said. “I ran eight miles this morning.”

Read more on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.