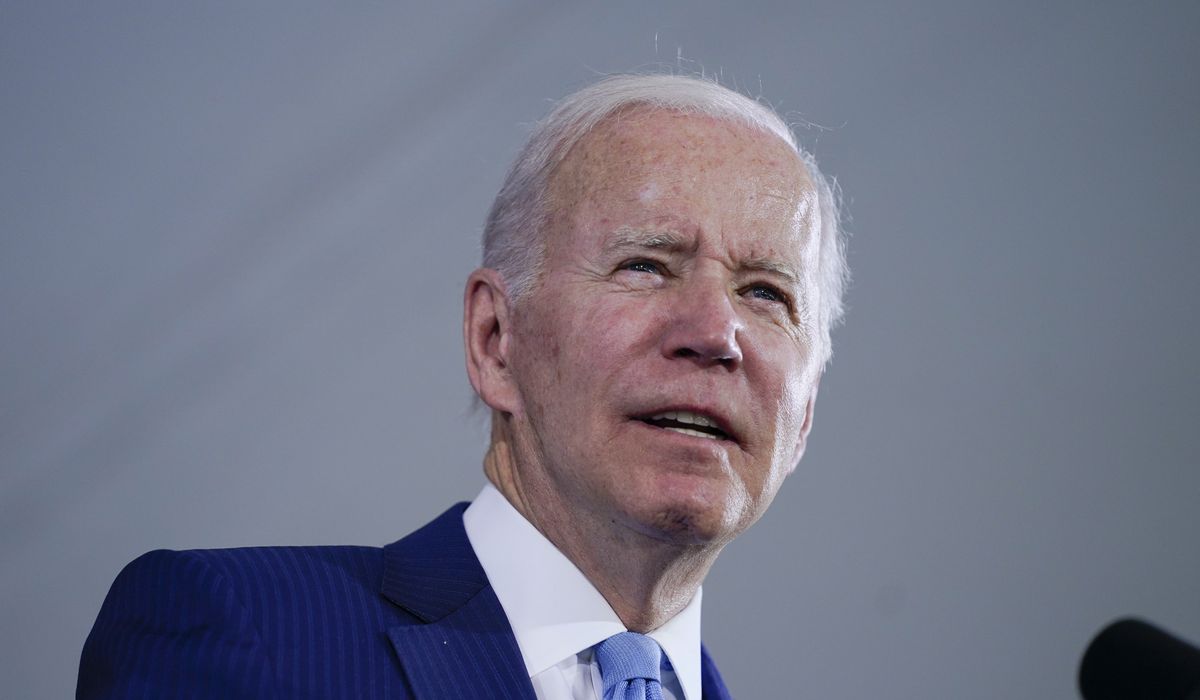

The Biden administration once hoped the 9th Summit of the Americas’ gathering in Los Angeles would be a chance to showcase U.S. leadership in the Western Hemisphere and a move past the often tense relations that prevailed under the Trump administration. But the weeklong gathering that starts Monday in Los Angeles has instead become so rife with ideological drama that it risks becoming one more headache for President Biden’s foreign policy agenda and his political standing at home.

It will be the first time the U.S. has hosted the event since the inaugural gathering in Miami in 1994. But what was supposed to be a muted celebration of hemispheric ties and cooperation — the only formal gathering of the leaders of the countries of North, South and Central America, and the Caribbean — has faced an unexpectedly rocky build-up.

Mexico’s leftist president hinted strongly last month that he won’t be coming to the June 6-10 summit, after objecting to U.S. plans to block representatives from the authoritarian regimes controlling Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua.

While saying Mexico would send a delegation, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador told reporters in Mexico City late last month, “It’s just that I will not attend if all countries are not invited. … What is this supposed to be: the Summit of the Americas or the Summit of the Friends of America?”

With leftist political movements on the rise in the region, the list of no-shows may grow: The leaders of Bolivia, Antigua and Barbuda, and Guatemala have reportedly also said they may not be coming, and leftist governments in Chile and Argentina have been critical of the U.S. stance for vetting the invitation list.

The standoff with Mr. Lopez Obrador, which remained unresolved as the summit’s opening approached, stems from longstanding division over whether or not non-democratic countries should be included in regional diplomatic gatherings of the Organization of American States (OAS), which organizes the Summit of the Americas roughly every three years.

The issue has become front and center, particularly since Mr. Biden has made the pursuit of stronger alliances among democracies a core pillar of his overall foreign policy. And while the administration has made some gestures to ease the confrontational policy toward Cuba and Venezuela pursued by President Trump, Mr. Biden faces political pressure from many in Congress and in a number of electorally important states to stick to the hard-line approach.

The administration’s dilemma risks undermining broader efforts by the White House to reassert U.S. influence in Latin America, at a moment when China is making inroads in the region, illegal immigration pressures are soaring at the Mexican border, and critics say democracy has been under attack over the past decade across the region.

“There are certainly signs that democracy has declined more in Latin America than in any other region over the past several years,” according to Michael Shifter, a senior fellow with the Inter-American Dialogue, who says Mr. Biden is likely to struggle to find common ground at the summit with populists now in power from Brazil and Mexico to Peru, Argentina, Honduras and beyond.

“Without even mentioning Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba, if you go country by country around the region, it’s hard to see that President Biden would have much affinity with any of the current cast of heads of state,” Mr. Shifter said. The reason, he said, stems largely from a “move toward greater populism in Latin America, with most of it, not all, but most of it being undemocratic.”

It’s a trend evident even in Colombia, arguably the most stalwart U.S. ally in South America in recent decades, where two anti-establishment presidential candidates — a leftist and a right-wing populist — are headed for a June 19 runoff, the result of which stands to redefine the U.S.-Colombia relationship.

Top Biden administration officials, including Vice President Kamala Harris and former Democratic Sen. Chris Dodd, the special envoy for the summit, have been racing to put out diplomatic fires ahead of the event even as the president and much of his team are consumed by the challenges posed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Mr. Shifter suggested the “best scenario” for Mr. Biden diplomatically will be to “avoid a disaster or a fiasco” at the summit in Los Angeles by pulling off a cordial if unproductive gathering of OAS leaders.

Others have been notably more blunt.

“The threat is not simply that this year’s summit will be a flop — yet another example of feckless U.S. policy toward Latin America,” according to longtime regional expert Christopher Sabatini, a senior fellow with the U.K.-based think tank Chatham House.

“Rather, the real risk is that — after nearly three decades of summitry — this year’s event may be interpreted as a gravestone on U.S. influence in the region,” Mr. Sabatini wrote recently in a commentary published by Foreign Policy. The article’s headline: “Biden Is Setting Himself Up for Embarrassment in Los Angeles.”

Diplomatic tightrope

Mr. Shifter emphasized that scrambled regional politics have frustrated Washington’s hopes to rally the OAS’s 34 other member nations around a cohesive democratic vision. The regional group has long suffered from a far lower profile than other international groupings.

“Latin America is moving not so much to the right or the left, but a lot of different directions at the same time and that makes it very hard to come up with a coherent approach to address democratic erosion and backsliding in the region,” he told The Washington Times in an interview.

The Biden administration has not been forthcoming about the guest list for the summit and has sought to downplay talk of friction over the invitation list.

Recent announcements from the White House easing pressure on Havana Caracas have triggered speculation that the administration is trying to placate Mr. Lopez Obrador — or at least stave off the prospect of a major diplomatic embarrassment in Los Angeles.

The U.S. has eased some economic sanctions on Venezuela, defending the move as a spur for talks between the regime of socialist President Nicolas Maduro and the U.S.-backed opposition. U.S. officials have said they’ll loosen some restrictions on travel to Cuba and allow Cuban immigrants in the U.S. to send more money back to the island.

But Mr. Biden risks domestic political backlash if he includes Cuba at the summit. Republican Cuba hawks such as Florida Sen. Marco Rubio have already warned Mr. Biden against inviting leftist authoritarian governments to the summit, saying it would provide a “massive international PR boost” to regimes such as Cuba and a “slap in the face” to the many Cuban-Americans who suffered at the hands of the government.

“Making concessions to authoritarians in our hemisphere only empowers dictators worldwide,” Mr. Rubio said in a statement last month. “The regimes in both Cuba and Venezuela have been staunch defenders of Vladimir Putin and his invasion of Ukraine. If the White House cozies up to them, we may see more countries in our own region turn a blind eye to Putin’s invasion.”

The political flak isn’t just coming from Republicans. Some key Democrats, notably Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman and Cuban-American Robert Menendez, have long opposed moves to ease the U.S. pressure on the communist government in Havana.

State Department spokesman Ned Price told reporters at a department briefing on May 20 that speculation about who may be attending is “understandable,” given that Mr. Biden will be the first U.S. president to attend the summit since 2015, when President Obama went to Panama. Mr. Trump skipped the next summit in Peru in 2018, sending Vice President Mike Pence in his place.

Mr. Price said the Biden administration intends to focus the Los Angeles summit on a range of factors, including migration, climate change and the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic.

“Our agenda is to focus on working together when it comes to the core challenges that face our hemisphere,” he said. “We’re a region that has endured economic shocks that are generating unprecedented levels of migration — not just to the United States, but also to Mexico and Central America.”

The migration issue can also be tied to the collapse of Venezuela’s economy over the past decade. Mr. Shifter pointed to the struggle among regional governments to deal with some 6 million Venezuelan refugees presently living in countries across South America.

The China factor

Questions about Mr. Biden’s approach to Latin America have piled up while his attention has been focused elsewhere during recent months — most notably taking a lead role in orchestrating the Western response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The president also travel to northeast Asia last month as part of his administration’s push to refocus overall U.S. foreign policy toward Asia, where the rising power of China is widely viewed to be Washington’s foremost long-term challenge.

However, many analysts believe a more clear-eyed U.S. focus on the relationship and economic investments in the Western Hemisphere would strengthen Washington’s hand in addressing that challenge.

Alternatively, neglecting Latin America could undermine Mr. Biden’s goals, according to Ryan Berg, a senior fellow in the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, given moves by China to make economic and diplomatic inroads in the region.

“It’s always been difficult for Latin America to get its due,” Mr. Berg told The Associated Press in a recent interview. “But we’re pretty close to being in a geopolitical situation where Latin America moves from a strategic asset for us to a strategic liability.”

Mr. Shifter generally agreed, although he suggested Washington faces an uphill battle countering Chinese investment in the region, particularly when it comes to offering alternatives to “huge infrastructure projects that China is supporting.”

“A lot of Latin Americans are basically pragmatic and will take advantage of opportunities that emerge — whether from China or the United States — if it means growing economically,” Mr. Shifter said. “I don’t think the very strong anti-China discourse coming from both parties in Washington really resonates with Latin Americans who feel the U.S. is not really offering something more attractive economically.”

“It’s not that the Latin Americans embrace the Chinese model, it’s just pragmatic necessity,” he added. “Latin Americans are seeing that China is very active and has a clear strategy and that the U.S. is not as present and committed as it claims that it is in the region. That’s a credibility issue.”