The generational impact of slavery led to one of the United States’ most tragic incidents: the largest mutiny in U.S. Naval history and the deadliest incident on the homefront during World War II.

Tucked away to the east of the San Francisco Bay Area, next to Clyde — a small community of fewer than 900 residents — sits a U.S. Army installation called Military Ocean Terminal Concord, or MOTCO, that is presently undergoing massive renovations. However before MOTCO became an Army installation, it was a Navy base known as Port Chicago Naval Magazine, serving as the main terminal for the shipping of general cargo and ammunition to troops in the Pacific during World War II.

In the segregated military, Black sailors were not allowed to serve in combat roles and instead were limited to support roles such as that of stevedore — someone who loads and unloads cargo. To many Black sailors who voluntarily enlisted to fight the Germans and Japanese, such forced assignments led them to perform dangerous jobs like handling explosive munitions. Even worse, the sailors were arbitrarily made stevedores at MOTCO without proper training.

The working conditions did not provide a better environment for these sailors. While most sailors handling and loading dangerous explosives were Black, their supervisors were white officers, who raced their crews against each other to boost their load rate and win bets. This practice often violated safety measures such as loading two ships at the same pier in an attempt to improve their rate.

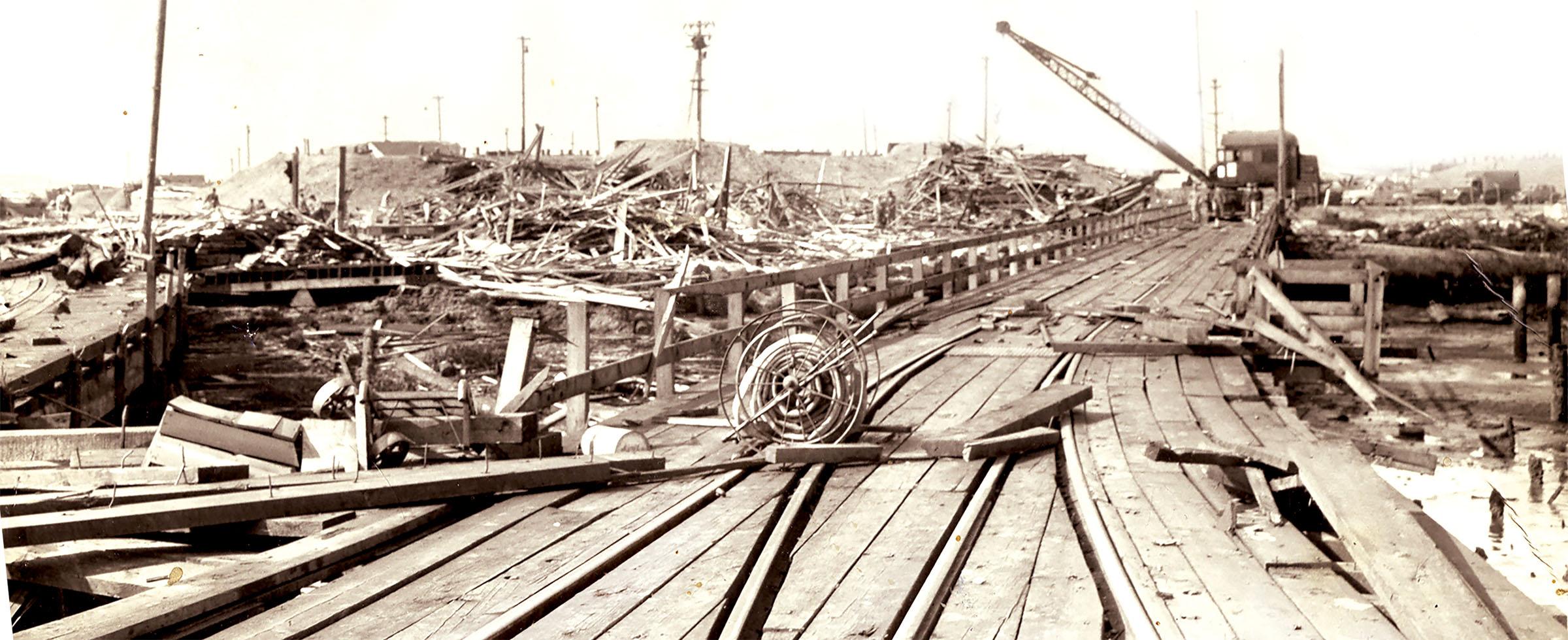

On July 17, 1944, two ships, S.S. Quinault Victory and S.S. E.A. Bryan were docked on the same pier when an explosion obliterated them both, along with 4,600 tons of ammunition, instantly killing 320 men and wounding hundreds more. The explosion was felt 30 miles away in San Francisco and registered a 3.4 on the Richter scale, leading to the highest number of deaths on U.S. soil during World War II (Hawaii did not become a U.S. state until 1959).

After the explosion, the Black sailors were given the order to return to duty while the white officers were granted leave to recuperate from the tragic incident. Fearing the return to an unsafe work environment, over 250 sailors refused their orders, only to be threatened by white officers that failure to obey orders was punishable by death. To many Black sailors who grew up in the Jim Crow era, a white man threatening to kill them provided a compelling reason to obey, even at the risk of one’s own safety.

Over 200 sailors returned to work, but 50 of them refused to work and insisted that they be provided with a safe working environment. These 50 sailors were immediately imprisoned and charged as mutineers and found guilty, in what became the biggest mutiny in U.S. Naval history. The sailors were dishonorably discharged and sentenced to 8-15 years in prison. One sailor, Freddie Meeks, was later pardoned by President Clinton, but 49 others took their last breath while still branded as mutineers.

The effects of that fateful day in July 1944 still reverberate, as unexploded ordinances have been unearthed in MOTCO as recently as November 2021. At the site of the explosion now lies Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Monument to remember the 320 victims who unnecessarily perished, and roads in MOTCO are named for the victims.

While the remnants of that day are visible within MOTCO, the incident has been all but forgotten by the public. The Port Chicago monument was the second least visited site in the National Park System in 2020, after the Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve in Alaska where it is only accessible by plane or boat. The comparison is truly disconcerting, considering that not even 30 miles west of the Port Chicago monument lies the second most visited site in the National Park System, the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

Today, an American flag silently waves in the bay breeze at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Monument to serve as a reminder of our past that is slowly fading away from the American consciousness. A stop sign is next to the monument, forcing construction workers to slow down and hopefully observe the memorial, if only for a moment.

+++

Capt. William Jung is a Project Manager with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stationed at Military Ocean Terminal Concord (MOTCO). The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.