An internal investigation released this week provides new insight into the Navy’s handling of a fuel leak in Hawaii that poisoned the water for thousands of military families, led to rashes and illnesses, and forced many from their homes.

The investigation, conducted by Navy Rear Adm. Christopher Cavanaugh, is the first account of its kind about the November 2021 fuel spill from the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility, a massive World War II-era fuel complex that supports military operations in the Pacific. The fuel, used by the military’s ships and aircraft, sits above the Southern Oahu Basal Aquifer, which is a primary water source for the island of Oahu.

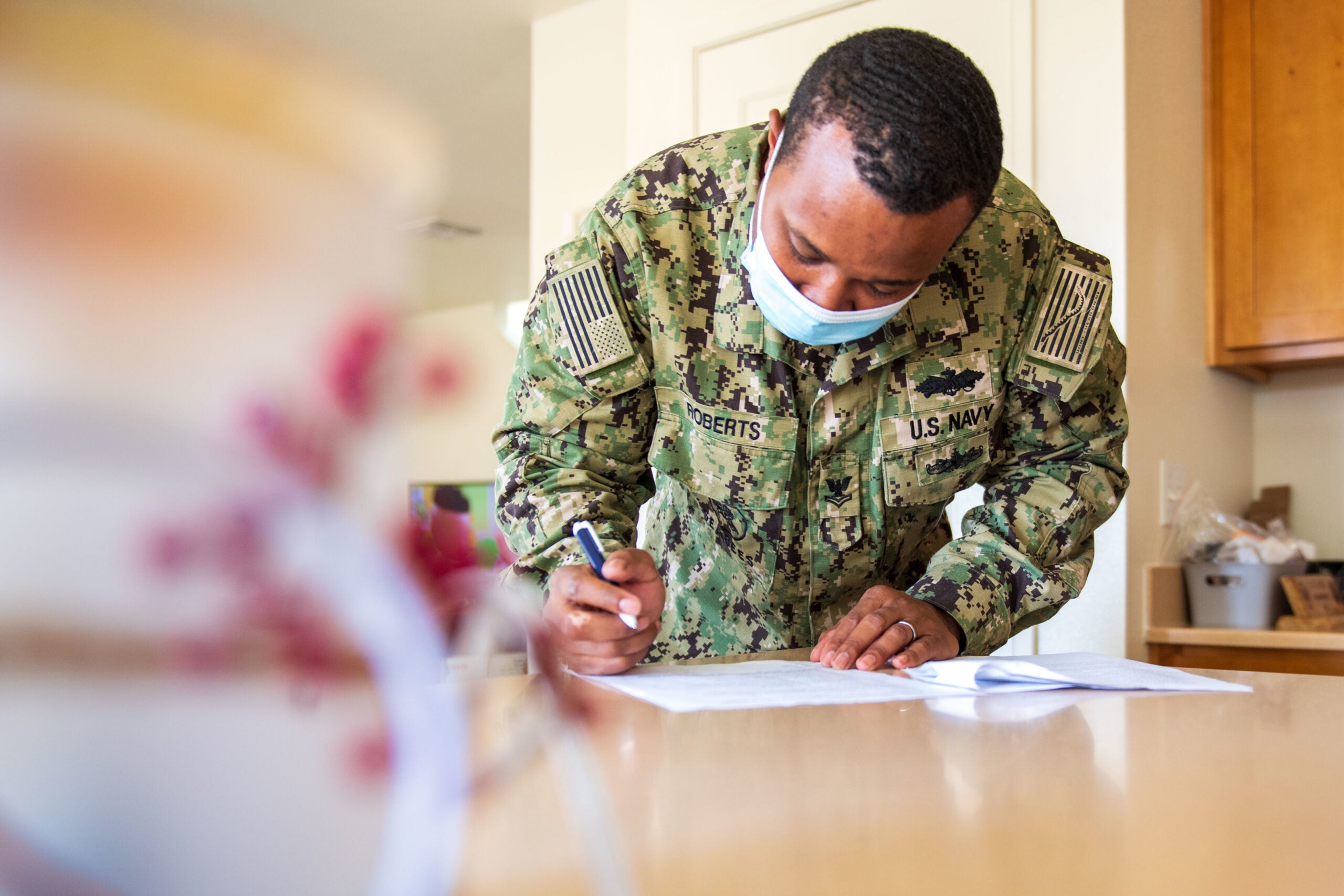

The investigation report details a series of failures and mistakes by Navy officials over the course of months, which all contributed to the crisis that began unfolding last fall. At the time, military families felt lied to and misled by the very military they were serving; while they were reporting an oily sheen in their water and a smell of fuel, the Navy told them the water was safe. And while the report maintains that there was “never an intent to mislead, lie, or obfuscate in any case,” it also acknowledged a breakdown in leadership and communication that led to families’ deep mistrust of their ability to handle the crisis.

“The contamination of drinking water from the Red Hill Shaft was the result of the Navy’s ineffective immediate responses to the 6 May and 20 November 2021 fuel releases at the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility (Red Hill), and failure to resolve with urgency deficiencies in a system design and construction, system knowledge, and incident response training,” Navy Adm. W.K. Lescher, the Vice Chief of Naval Operations, wrote in the report. “These deficiencies endured due to seams in accountability and a failure to learn from prior incidents that falls unacceptably short of Navy standards for leadership, ownership, and the safeguarding of our communities.”

The Navy agreed earlier this year to defuel the Red Hill facility, after initially fighting the order to do so from the State of Hawaii.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

While there have long been reports of leaks from Red Hill, the problems in the investigation began in May 2021, when operator error during a fuel transfer procedure resulted in the spill of more than 20,000 gallons of fuel. However, officials thought that only 1,618 gallons of fuel had leaked, despite noticing that one fuel tank “was short 20,000 gallons,” the Associated Press reported, “but believed it had flowed through the pipes.”

In fact, that fuel contaminated a fire suppression system retention line and wasn’t discovered until the November 2021 incident. Red Hill officials did, however, see that there was a 19,983-gallon drop in one of the fuel tanks on May 6, but believed it was put into a pipeline. The report says that the Naval Petroleum Office Deputy Officer in Charge, who was appointed to investigate the May 6 fuel spill, did not include the nearly 20,000-gallon loss in his report because he “did not deem it relevant.”

In September, a root cause analysis of the incident also identified a “net volume drop of 473 barrels … which equates to 19,866 gallons.” But “none of the technical personnel that reviewed the report identified this as an issue worth exploring.” The report released this week identifies multiple occasions in which officials, including “senior leaders from the [U.S. Pacific Fleet] and [Commander of Navy Region Hawaii] staffs” did not address the fuel discrepancy or recommend any action regarding it.

The problem became impossible to ignore just two months later.

On Nov. 20, 2021, a Red Hill watch stander “inadvertently struck a low point drain valve … cracking the PVC pipe and spilling up to 19,377 gallons of fuel deposited there on 6 May.” At first, officials thought the leak was water. But after the first report, an official reported “that the leak smelled like fuel,” according to the report. The fumes were so bad, in fact, that one man who was present had to leave the area to wash “his eyes with water, because they were burning.”

Navy officials provided conflicting information regarding the spill over the following days due to a breakdown in communication and understanding of the problem, the report said. First responders knew “the spill was mostly fuel,” according to the report, but the commanders of Fleet Logistics Command Pearl Harbor and Naval Facilities Engineering Systems said they “understood it to be water” because of the “first reports they received.”

Just hours later, once the two commanders were at Red Hill, they saw firsthand that the leak “was fuel and not water,” the report said. And while the commanders “believe that they communicated that the fluid was mostly fuel” in an update to other officials, the report said those officials told investigators they thought that meant “that the fluid was water with a smell of fuel.”

As military families began calling in to report a chemical smell and oily sheen in their water, Navy officials put out press releases saying the water was safe to drink. One of the biggest instances of conflicting information came on Nov. 29, when the base commander, Capt. Erik Spitzer, issued a statement to residents that there were “no immediate indications that the water is not safe,” and that he and his staff were drinking the water.

Later that evening, however, the Hawaii Department of Health issued a press release recommending anyone using the Navy water system no longer use the water for cooking, drinking, or oral hygiene.

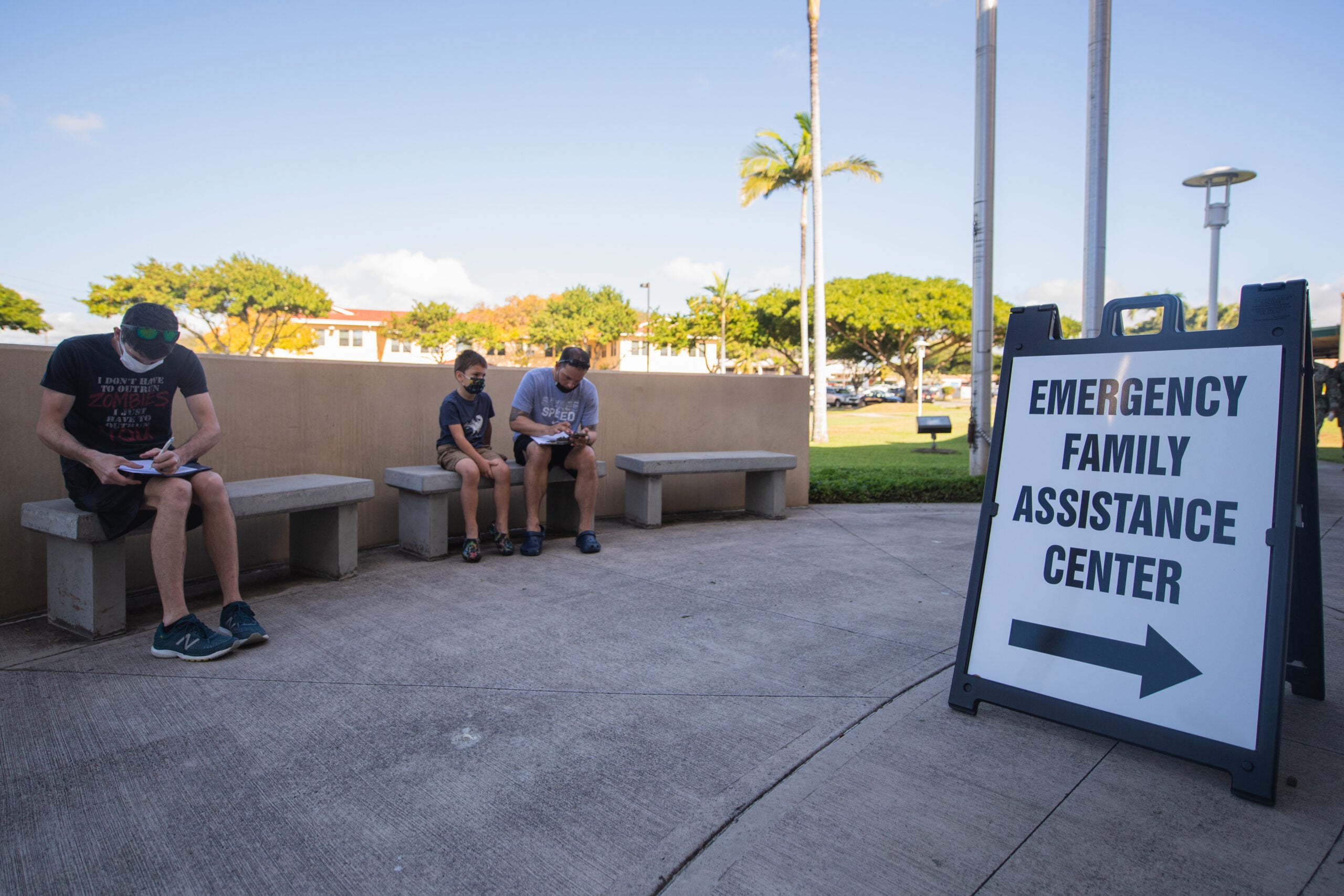

Fear, distrust, and frustration among families towards the Navy subsequently boiled over during town halls, where officials were pushed to provide answers. Residents saw officials acting with no urgency, and believed they were purposefully hiding the severity of the situation from them, even as families began moving into hotels and leaving their homes to get away from the water.

The Navy’s investigation said that all communications from the service “were developed with the intent of being truthful based on the facts known at the time,” but acknowledged that there “were missteps.” It also identified four main points that hurt the public’s trust in the Navy, including Spitzer’s message that he and his staff were drinking the water on Nov. 29. Other instances included the “misalignment in message and approach” between the Navy and the Hawaii Department of Health, and the difference in response between the Army and Navy.

While the Army was hailed as being proactive and attentive to families’ challenges, the Navy was criticized as dismissive and insensitive. The Navy’s investigation report said the “misalignment’ between the two services “significantly hurt public trust” because it created “the perception that the Navy was lagging the Army’s actions.” The “differences in approach,” according to the report, resulted in the Navy waiting for data to confirm contamination before taking action while the Army and Department of Health did not wait and took action immediately.

The report concluded that human error in “failing to properly respond” to the fuel spill in November was “the primary cause” of the contamination. Notably, the report found “no evidence” that Red Hill officials had “ever conducted … even one drill to prepare for a spill.”

The spill on May 6 was not followed by additional training or any measures to prevent it from happening again in the future. There “was no learning or assessment with regard to response efforts following the May spill,” the report said, concluding that. key lessons “were never learned.” Had that happened, the report said that the water may not have been contaminated in November.

“An effective spill response training and drill program would likely have revealed gaps and seams in the C2 [command and control] as practiced, flaws in the assumptions about who would respond, and how the team diverged from requirements and the plan,” the report says. “Which in turn would most certainly have improved the response to the November spill and possibly identified the risk to the Red Hill well before the drinking water distribution system was contaminated.”

Exactly how much damage the contaminated water did to families and their health remains unclear. But exposure could result in a “whole variety of outcomes,” Dr. Wendy Heiger-Bernays, a clinical professor in the Department of Environmental Health at the Boston University School of Public Health told Task & Purpose in January, including effects “on the gastrointestinal, the digestive system, blood-forming cells, the neurological system, and certainly irritations with the skin.”

Adm. Sam Paparo, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, told reporters on Thursday that the Navy has to “get real with ourselves” and “be honest about our deficiencies.” He also recommended that 48 other defense fuel storage facilities around the world be reviewed.

“We cannot assume Red Hill represents an outlier,” Paparo said. “And similar problems may exist at other locations.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.