Senate lawmakers want the military to end a program created after the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol to eliminate White nationalists and other extremists from its ranks.

The language calling for an end to the effort is contained in a report accompanying the Senate’s annual defense policy bill, and it cites a Pentagon analysis showing that the military has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars and devoted millions of hours searching for extremism in its service branches, even though it is exceedingly uncommon.

“The committee believes that spending additional time and resources to combat exceptionally rare instances of extremism in the military is an inappropriate use of taxpayer funds, and should be discontinued by the Department of Defense immediately,” senators advised in the report.

The language, which was first reported by Roll Call, is nonbinding but “sends a strong signal to the Department of Defense that the Senate Armed Services Committee agrees the military should devote its time and resources to our most serious threats — China and Russia,” a Republican aide told The Washington Times.

The Pentagon vowed to investigate extremism after it was discovered that some of those arrested for participating in the Capitol riot were either former or current members of the military.

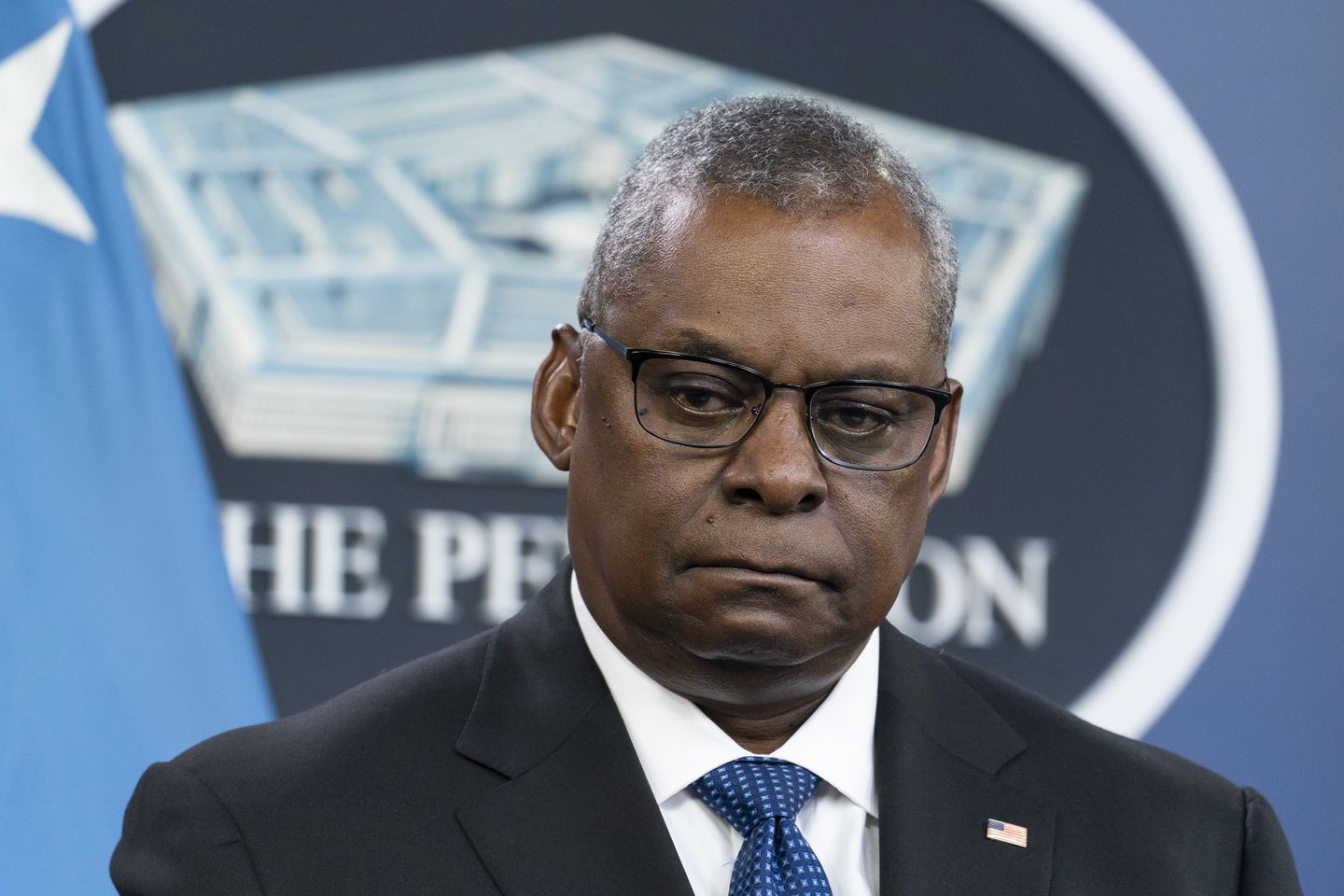

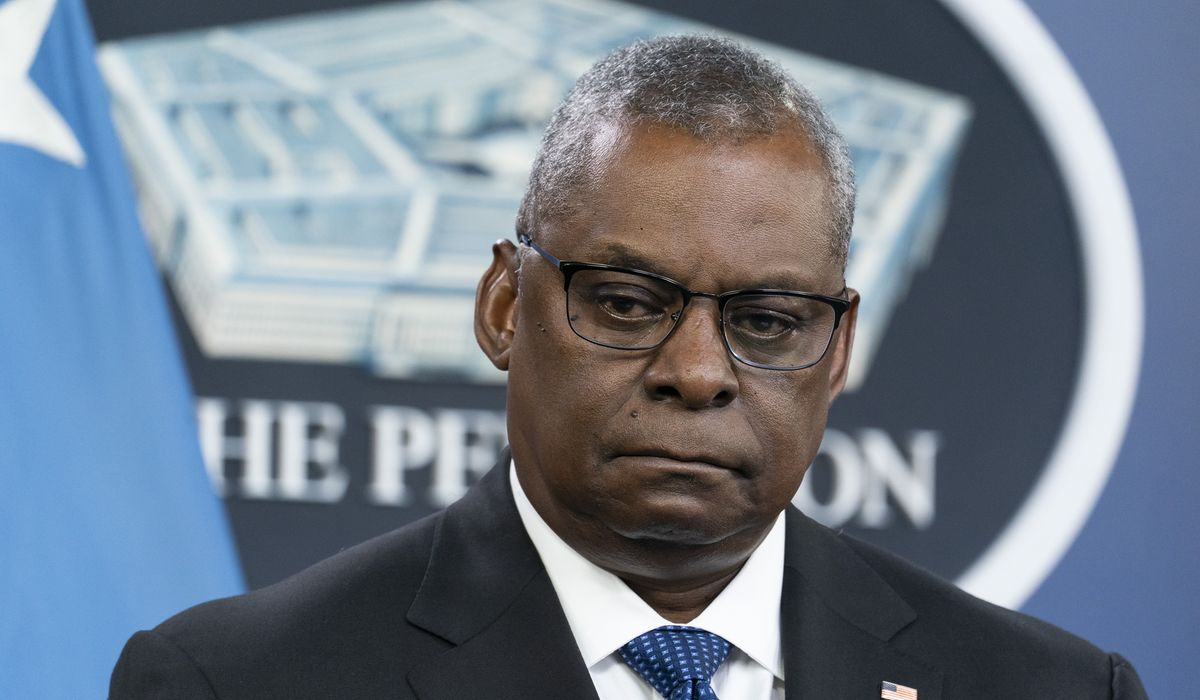

Weeks after the riot, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin ordered a departmentwide “stand-down to discuss the problem of extremism in the ranks.”

The stand-down diverted service members from their usual duties and required them to instead hold discussions on extremism.

John Kirby, a Pentagon spokesman at the time, said the stand-down “was also about listening to service members and civilians and their own feelings about extremism.”

Mr. Austin expanded the effort in April 2021 by establishing the “countering extremist activity working group,” tasked with “implementing immediate actions and formation of additional and long-term recommendations to address perceived extremism in the ranks.”

The group determined there were 100 cases of prohibited extremist activity among 2.1 million active and reserve personnel, or a case rate of 0.005%.

Senate Armed Services Committee Republicans, concerned about the military wasting time and resources, demanded that military brass provide an accounting of the effort.

Gen. Mark A. Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, responded in writing in January. He told the panel that the military had devoted 5,359,000 hours and spent $500,000 on the stand-down.

Sen. James M. Inhofe of Oklahoma, the top Republican on the committee, told The Times that the diversion of resources was not justified and said the military should instead focus on keeping up with Russian and Chinese military advances, which he said pose real threats to the U.S.

“We have lost that No. 1 position in several pieces of equipment, and the Chinese and the Russians actually have some things that we don’t have,” Mr. Inhofe said. “That’s scary. And the idea that they’re wasting all this time on social issues, it’s very offensive to me. We’ve got a country to save. I’ve got a whole houseful of kids and grandkids to save.”

Republicans have become increasingly critical of the efforts of top military officials to implement liberal policies aimed at diversity and inclusion while military preparedness appears to be threatened and fewer people want to enlist.

The five military branches have been unable to reach recruiting goals this year and are down by 23% of their annual target, Pentagon officials said last month.

Sen. Joni Ernst, an Iowa Republican who served as a lieutenant colonel in the Iowa National Guard, said the military has policies in place to deal with extremists and does not need a special program devoted to the issue.

“They always discipline those that are engaged in bad activity,” Ms. Ernst said. “That’s not a concern.”

The language in the defense bill was authored by Sen. Dan Sullivan, an Alaska Republican who is a colonel in the Marine Corps Reserve. It is facing Democratic opposition, though none of the Democrats on the Armed Services Committee, including Chairman Jack Reed of Rhode Island, made an effort to block it.

“I didn’t realize that was in the report,” Sen. Tim Kaine, a Virginia Democrat on the committee, told The Times. “I don’t want that.”

Whether the language survives final passage in Congress will largely depend on conference negotiations with the Democratic-led House, which produced its own defense policy bill that does not include a directive to end anti-extremism programs in the military.

Republicans have more influence over the defense measure in the Senate thanks to the chamber’s 60-vote threshold, which requires bipartisan agreement to pass most bills.

“This issue is going to be worked out within the context of the conference, where one side is looking for a much more systematic approach toward extremists in the ranks,” Mr. Reed said. “And we’re going to work it out.”