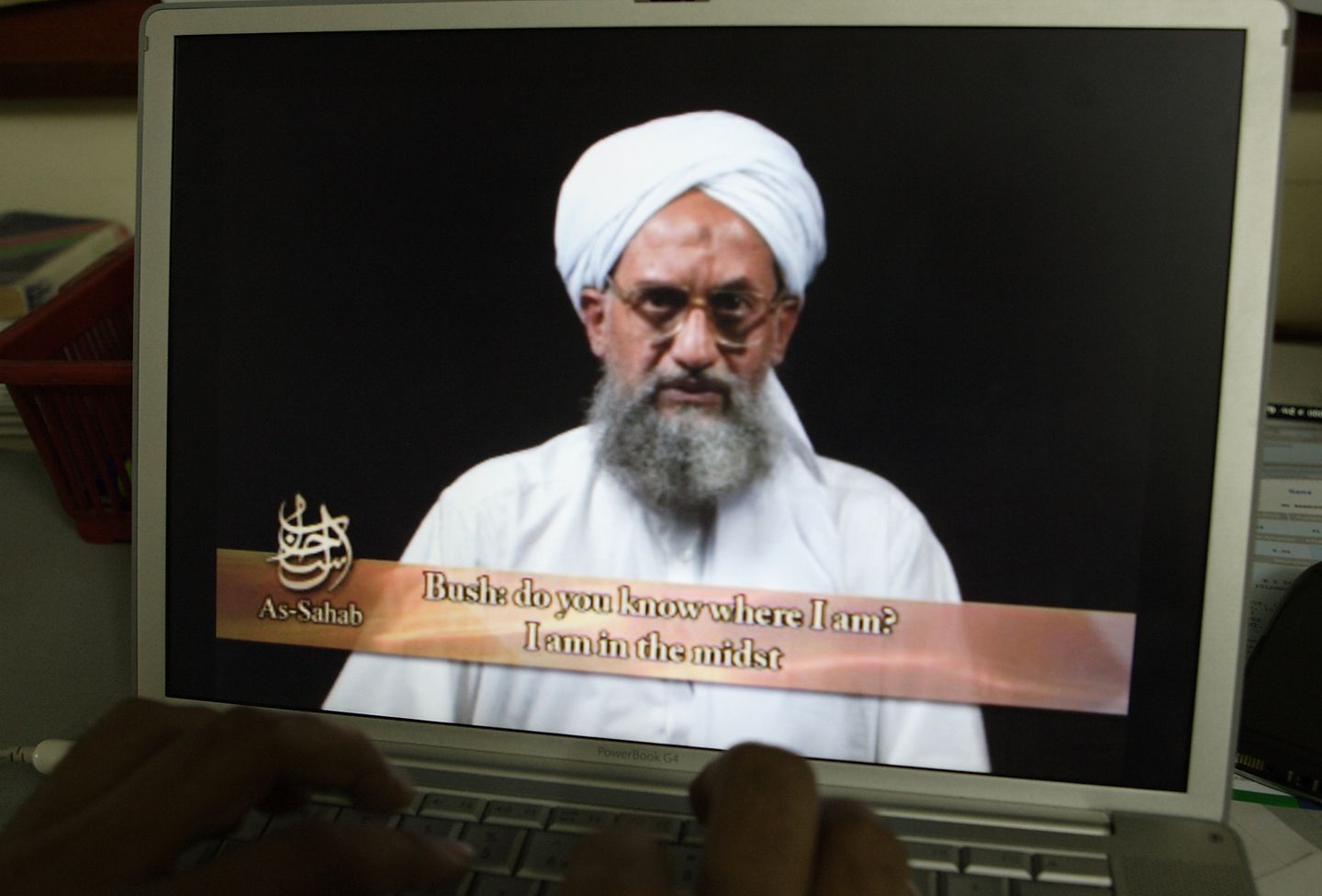

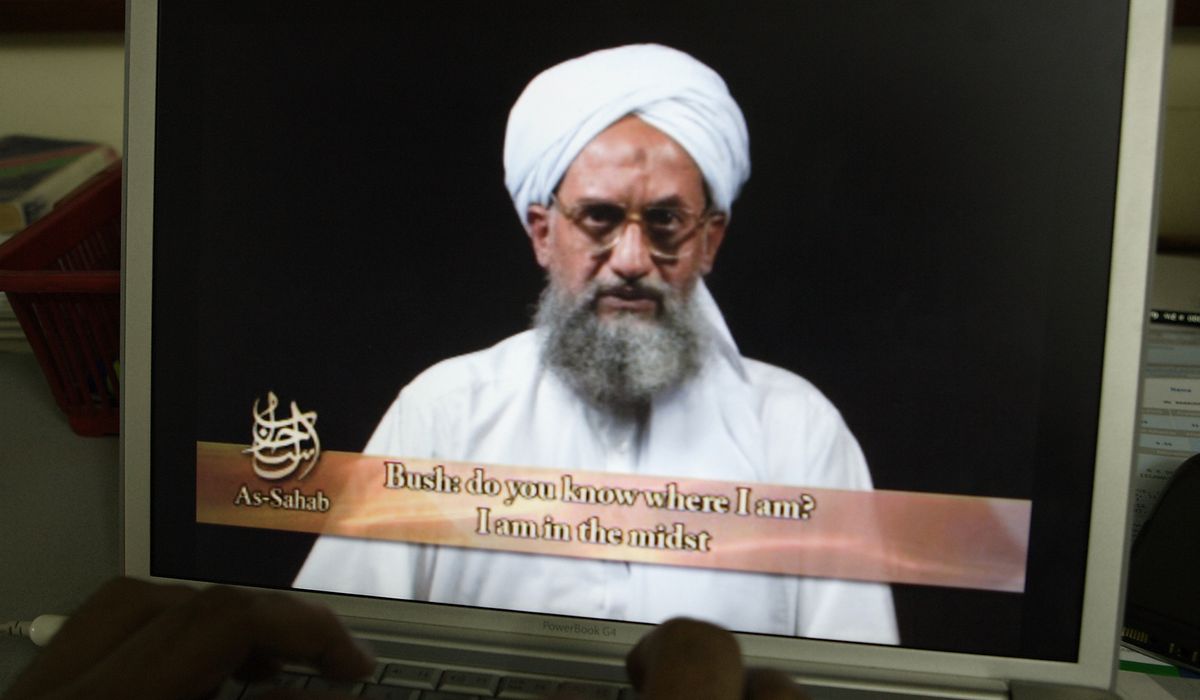

On its face, last month’s strike on al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahri proved U.S. forces can still carry out military and intelligence missions in Afghanistan even with American boots no longer on the ground.

Beneath the surface, however, counterterrorism insiders and foreign policy analysts say the bombing of al-Zawahri’s safehouse in Kabul only exposed much deeper long-term problems for the U.S and the seemingly never-ending fight against radical Islamic extremism. Chief among them are the clear links between the Taliban and al Qaeda, which some specialists describe as virtually unbreakable and likely to grow even stronger as more time passes, with the Taliban cementing their rule and no steady U.S. presence in Afghanistan to act as a counterbalance.

The ability of the Pentagon and the U.S. intelligence community to track and contain the spread of terrorist networks in Afghanistan may be severely limited in the years to come. The al-Zawahri strike, analysts say, was something of a unique case. The al Qaeda leader — after eluding a global manhunt for more than two decades — was apparently undone because of his own tradecraft sloppiness, including a penchant for spending time on his balcony in clear view of anyone on the streets below. Once U.S. intelligence could positively identify him, that habit made him a relatively easy target for long-range U.S. drones launched from outside Afghanistan.

But more complex missions remain difficult, if not impossible, to organize from “over the horizon.” Special forces raids involving ground teams — such as the 2011 mission in Abbottabad, Pakistan, that killed Osama bin Laden, or the 2019 operation in Syria that killed Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi — would be exceedingly difficult in Afghanistan, for a host of logistical and geopolitical reasons.

“The strike on al-Zawahri is really the best of times and the worst of times,” said Nathan Sales, the State Department’s counterterrorism coordinator under former President Trump. “The upside is it shows that in exceptional cases, the U.S. still has the capacity to take terrorists off the battlefield. The downside, which I think deserves more attention, is it shows al Qaeda and the Taliban continue to collaborate to the point that al Qaeda’s head honcho felt comfortable living in a Taliban safehouse right in the heart of the capital.”

If that collaboration eventually leads to threats to U.S. interests abroad or perhaps even the American homeland, a more significant military mission would face serious hurdles.

“It would be much harder, operationally and diplomatically, to carry out an Abbottabad-type raid or a Baghdadi-type raid,” Mr. Sales said. “Where are you going to stage your troops? We could do Abbottabad because we had a substantial U.S. military presence in Afghanistan. We could do Baghdadi because we had a substantial troop presence in Syria and Iraq.”

Both Mr. Trump and President Biden, who share little in common politically, refused to budge from their position that it was past time for U.S. troops to leave Afghanistan, despite pleas from top American generals to keep a small but symbolically potent force in place to bolster the U.S.-backed government in Kabul.

Mr. Trump opened direct diplomatic negotiations with the Taliban despite harsh criticism from within his own party, sealing a withdrawal agreement with the insurgents without first getting buy-in from the Kabul government. Biden pushed ahead with the withdrawal process and timetable even as critics said the Taliban were not holding up their end of the accord and U.S. military advisers privately warned him that the Afghan government was sure to collapse in short order without American and Western backing.

Both administrations have sought to turn America’s attention, militarily and geopolitically, toward Asia, as China continues its rise as both a military and economic power, but some argue forcefully that the new reality in Afghanistan makes that more difficult. Instead, more than two decades after the 9/11 attacks, the U.S. finds itself forced to keep at least one eye on Afghanistan and its potential to again become the epicenter and sanctuary for global Islamic extremism movements.

“The overall strategic picture emerging from enduring al Qaeda-Taliban association is bad news for the U.S. government, which has been wanting to pivot away from the fight against terrorism toward strategic competition with China and Russia,” Asfandyar Mir, a senior expert at the U.S. Institute of Peace’s Asia Center, said during a recent forum. “It appears the U.S. government still faces formidable terrorist adversaries who are able to exploit grievances, alliances and state support to recover from losses and stay in the fight. America can’t afford to take the eye off its terrorist adversaries.”

As a tactical matter, the U.S. still faces a host of unanswered questions about what it can and cannot do to stop the spread of extremist forces in Afghanistan.

Over the past year, for example, the Biden administration has had little apparent success finding new countries near Afghanistan willing to host American counterterrorism assets for the long term. That lack of staging areas would greatly complicate any potential missions relying on ground forces, making them far more dangerous.

Potential hosts in the region, particularly Central Asian nations such as Uzbekistan, have come under pressure from Russia, along with behind-the-scenes pressure from China, to deny U.S. overtures.

Even Pakistan, which has its own complex two-decade history with the U.S. on matters of counterterrorism, is walking a fine line on the issue. Last month, Taliban officials publicly accused Islamabad of allowing U.S. drones to fly through Pakistani air space to conduct missions in Afghanistan, most notably the strike on al-Zawahri.

Pakistani officials denied the charges.

“In the absence of any evidence … such conjectural allegations are highly regrettable and defy the norms of responsible diplomatic conduct,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Asim Iftikhar Ahmad said in a statement, according to Voice of America.

History repeats itself?

Mr. Ahmad also publicly admonished the Taliban to live up to the agreement it signed with the Trump administration in early 2020, in particular not to allow terrorists free rein in the country as happened during the first Taliban regime in the lead-up to the 9/11 attacks, which were conceived and prepared by bin Laden, al-Zawahri and other top al Qaeda figures from camps inside Afghanistan.

“We urge the Afghan interim authorities to ensure the fulfillment of international commitments made by Afghanistan not to allow the use of its territory for terrorism against any country,” he said.

That deal called on the Taliban to never again allow terrorist groups to use Afghanistan as a base of operations and not to conduct operations against U.S. and allied forces as the deal was being implemented. In exchange, the U.S. would withdraw all of its troops from the country.

But the Taliban offered little evidence it intended to follow through on that process. Throughout the months-long American military drawdown, reports from the Pentagon, the United Nations and other organizations consistently said that al Qaeda remained present in Afghanistan, despite the Taliban’s public assurances to the contrary. Al-Zawahiri’s comfortable living arrangement in Kabul offered more proof that the Taliban is either unwilling or unable to purge the country of terrorists.

In addition, a ruthless offshoot of Islamic State, a rival to al Qaeda, has been able to establish its own beachhead inside Afghanistan.

By following through on the withdrawal anyway, and executing it in such a chaotic fashion with the whole world watching, the Biden administration has made America less safe, critics say.

“We are more likely to be attacked like New York City was 20 some years ago, we’re more likely to be attacked from [Afghanistan] today than we were just one year ago,” former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said during a recent appearance on the Cats Roundtable radio program.

As former President Trump’s secretary of state, Mr. Pompeo was in a key position during U.S. negotiations with the Taliban. But Mr. Trump and his advisors insist they would not have forged ahead with the pullout as Mr. Biden did in the face of clear evidence that the Taliban leaders had failed to live up to their promises, or without a clearer plan for how the U.S. would maintain counterterrorism capabilities in the theater.

The Biden administration argues the U.S. has already reaped strategic benefits from the Afghan pullout — being able to focus heavily on the Russia-Ukraine war without distractions, for one thing — and a recent U.S. intelligence community assessment offered a relatively optimistic take on the state of terror movements inside Afghanistan a year after the American troop pullout.

The joint U.S. agency assessment concluded that al Qaeda so far has not been able to reconstitute the network it once had in the country and that only a “handful” of the once-feared terror group’s members remain, the New York Times reported last month.

But with no American troops in Afghanistan and a Taliban government that’s proved to be unreliable, military officials fear the country could eventually unravel to the point that America is forced to return.

Asked recently whether U.S. troops may need to go back to Afghanistan, retired Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie seemed to leave that door open.

“I know this: It is in the best long-term interest of the United States to not allow these centers of violent extremism to grow and expand in Afghanistan. And I believe under the current Taliban regime, that’s probably what’s going to happen,” said Gen. McKenzie, who led U.S. Central Command during the 2021 withdrawal.

“The last time I was looking at intelligence, that was a position we had,” Gen. McKenzie told Fox News Sunday in a recent interview. “I follow it like everybody else does now, in the newspaper and other sources. But I see nothing to change that opinion that the threat is growing in Afghanistan and it’s merely a matter of time.”

Biden administration officials say that the U.S. is prepared to deal with the threat. They stress that the strike on al-Zawahri proves that the U.S., despite its limited capabilities in Afghanistan, can still take out terrorist figures when necessary.

“Ask the members of al Qaeda how safe they feel in Afghanistan right now,” White House national security spokesperson John Kirby told reporters last month following the al-Zawahri strike.

“I think we proved … that it isn’t a safe haven and it isn’t going to be going forward,” he said.