In 1994, Frank Butler was wheeled into an operating room for knee surgery on a torn meniscus — the result of running too hard with his sons at Fripp Island, South Carolina. A Navy SEAL and medical doctor, Butler watched the surgical team prep him for the procedure, feeling the sedatives set in.

But even hazy from the medication, he noticed when they put a tourniquet on his leg.

“I was aware that both the military and the civilian sectors discouraged tourniquet use,” Butler told Task & Purpose. “But when I had my surgery done and they used the tourniquet on me, the light came on.”

At the time, Butler was director of the Navy SEAL’s new biomedical research program and had been looking into battlefield trauma care and, specifically, deaths during the Vietnam War that resulted from soldiers bleeding out from their arms or legs.

When he awoke from surgery, Butler asked his surgeon about the tourniquet, mentioning that military trauma courses of the time taught that the tool could be dangerous if used improperly, leading to damaged limbs and even amputations.

“He said, ‘Frank, what can I tell you? We use tourniquets in the operating room every day. They don’t cause problems. Nobody’s leg has to be cut off,’” Butler, who retired as a captain, told Task & Purpose. “It became apparent that there was a huge disconnect between what people do in the operating room and what we do on the battlefields.”

Butler’s knee injury and his chat with a surgeon came at a key moment for military trauma medicine. At the end of the 20th century, most U.S. troops did not carry tourniquets and military training courses dissuaded even trained medics from using them often, adhering to the conventional wisdom Butler had during his knee surgery, that extended lack of of blood flow to a limb was too big a risk for anything but the most severe bleeding.

But Butler was not just a dad who’d blown his knee on a vacation. A former SEAL platoon commander, he’d gone to medical school and helped craft medical procedures and policies for medics across the special operations world. Over the next 20 years, Butler turned that moment on a surgeon’s table into a revolution in military medicine, standardizing the use of tourniquets across the military.

As the chair of the committee that produced the military’s guidebook for battlefield medicine — Tactical Combat Casualty Care — for 11 years, he helped bring numerous changes to how combat casualties are treated on the battlefield. In the late ’90s and into the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the committee rewrote rules for how U.S. medics control excessive bleeding, deal with shock from blood loss, and manage pain.

Earlier this month, Butler was recognized by the White House with the Presidential Citizens Medal, presented by President Joe Biden. The award recognizes those “who have performed exemplary deeds of service for their country or their fellow citizens.” The White House announcement said Butler “transformed” the U.S. military’s battlefield trauma care and “saved countless lives.”

Butler said he believes it’s the first Presidential award to recognize combat casualty care achievements. He hopes the award can solidify those advances in the “interwar years.”

“The military in the past has occasionally forgotten about some of the advances that were achieved during wartime because once the war is over, people’s attention turns to other things,” he said.

The use of whole blood products is one such case, he said. Americans entered World War II without a whole blood program, developing one in combat. But half a century later, the U.S. military again entered into conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan “without widely accepted policies directing whole blood transfusion and the only supply being component therapy.”

Watching hard-learned lessons be lost was at the root of Butler’s tourniquet work. In Vietnam, studies showed that up to 90% of battlefield fatalities occurred before casualties reached a hospital, with most troop deaths being from hemorrhaging. In his own research, Butler calculated that nearly 8% of Vietnam deaths due to excess blood loss were preventable.

“That means that over 3,400 lives were lost because they didn’t have a tourniquet applied to the bleeding arm or leg. I mean that’s a stunning number,” Butler said about Vietnam. “That’s more people that were killed at Pearl Harbor, more people than were killed at 9/11 and yet, because we weren’t tracking it in real-time, people didn’t realize it until after the war, and nobody made the changes to rethink about tourniquets while the conflict was underway.”

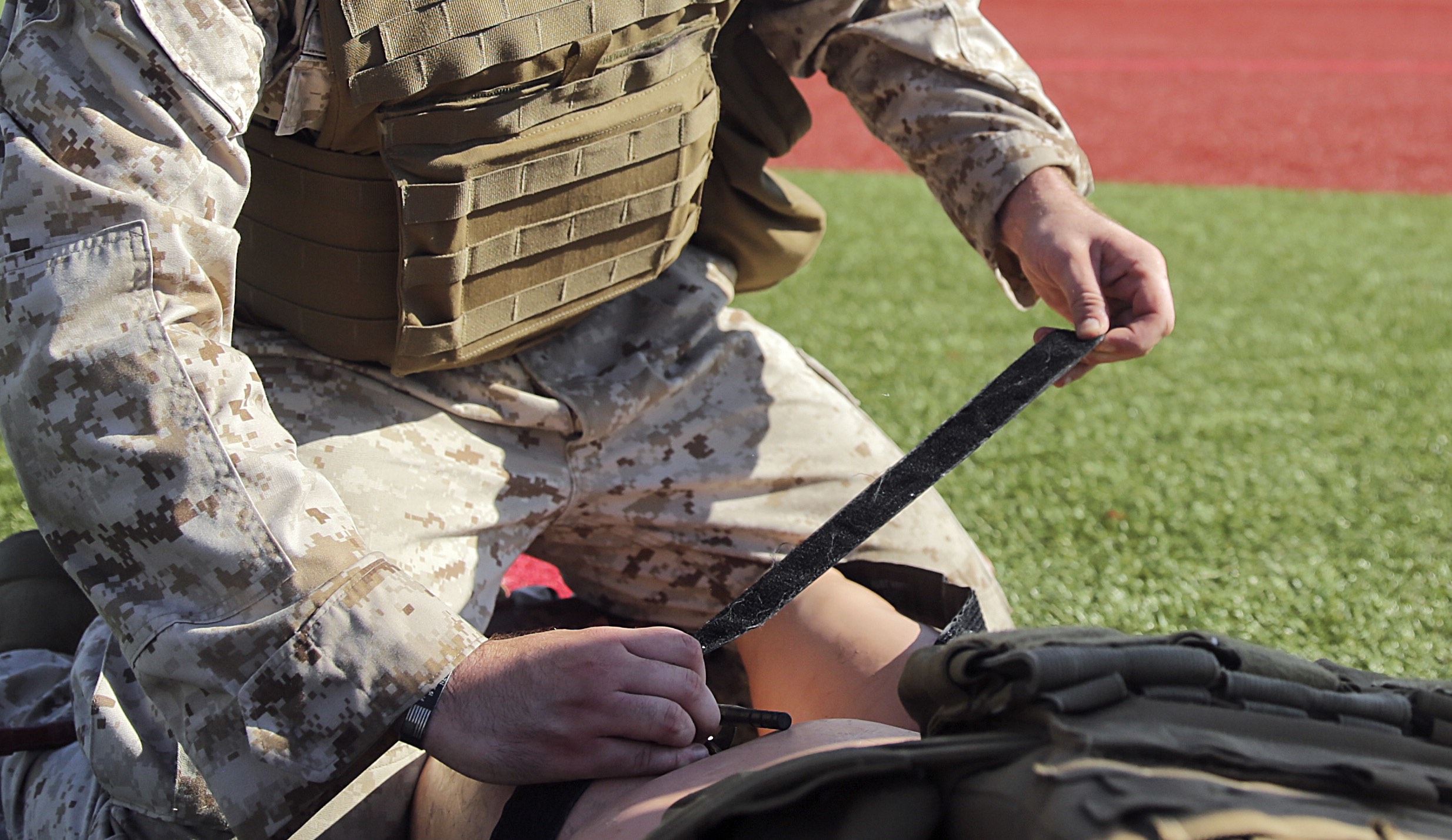

Early tactical care guidelines were published in 1996 and in 2001 the Butler-led committee made updates in the Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook. The Butler-led committee changes included recommendations for medics to incorporate “high and tight” tourniquet placement, followed by rapid transport to a surgical setting.

By 2008, tourniquets were issued as basic combat gear to virtually every American service member. Some Army uniforms even had them built-in.

Butler’s focus on tourniquets in the military even spilled over to civilian medicine. Following the Sandy Hook, Connecticut mass shooting, a local trauma surgeon convened a panel to discuss emergency response, including how to treat severe bleeding from gunshot wounds in mass casualty events. Those discussions were the starting point for “Stop the Bleed,” a campaign to bring wider adoption and education of tourniquets to emergency services and even civilian places.

However, as tourniquet use has spread, medical studies have found a lack of proper training, leading some providers to overuse them, causing amputations and even death. In one of Butler’s own studies published in July 2024 on combat care in the Ukraine-Russia war, his research found that Ukrainians have seen an “unnecessary loss of extremities” and “life-threatening episodes” due to tourniquets which Butler linked to a lack of training emphasis on when the tool should or should not be used.

Medical standards recommend that providers use a tourniquet to stop a patient’s bleeding but also say that it should be taken off as soon as possible when they reach a hospital or surgical setting — an obstacle harming Ukrainian combat casualties and potentially Americans in a future fight.

The U.S. Tactical Care guide advises that medics facing periods of extended care should “convert” tourniquets — either removing them when a wound’s bleeding is controlled or moving them to a more effective spot on the body — as soon as tactical conditions allow. But it also notes that medics should simply leave a working tourniquet in place if a patient is likely to reach higher care within two hours.

“In Iraq and Afghanistan, because we got the casualties to the hospital so quickly in helicopters, it wasn’t a problem. But in Ukraine, where the evacuation times can take six to 12 hours or longer, it is a problem,” he said. “The fact that you can put a tourniquet on and leave it there safely for an hour doesn’t mean you can leave it there safely for 12 hours.”

Butler’s study notes that Ukraine’s “unnecessary” tourniquet-related deaths could pose a similar risk to U.S. forces in future combat where surgical evacuations are delayed because of problems imposed by enemy aircraft, which the Pentagon calls “denied air superiority.”

“If the U.S. military goes and tries to help in a combat scenario in the Pacific, the Chinese have a lot of drones, and they will be doing the same things that Russian drones are doing now – trying to keep our wounded soldiers and marines from being transported off the battlefield,” Butler said. “That’s not a medical problem, really it’s a drone problem.”

Future tactical care

Over the course of his career, Butler served as command surgeon for U.S. Special Operations Command, a surgeon for a joint task force in Afghanistan in 2003, and director of biomedical research for Naval Special Warfare Command between 1990 and 2004.

Today, as a certified ophthalmologist, he teaches as an adjunct professor of military and emergency medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Maryland, and consults with the Joint Trauma System committee that meets twice a year to discuss innovations and trends in prehospital trauma care. One of Butler’s more recent concerns is retaining the medical knowledge from previous conflicts and standards of care that could be on the chopping block.

“We’re fighting to keep them in there because now after the war is over, these kinds of issues are looked at in the context of what’s going on in the nation as a whole,” he said.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Storied Marine infantry battalion to be transformed into Littoral Combat Team

- Soldiers are turning to social media when the chain of command falls short. The Army sees it as a nuisance.

- Marine recruit uniforms were photoshopped on at boot camp

- Army doctor pleads guilty on first day of trial in largest military abuse case

- Air Force ‘standards update’ includes more inspections and review of ‘waivers and exceptions‘